“Sexing Histories of Revolution” Roundtable – Post #2

In this series, contributors explore sex and sexual revolutions in the revolutionary era.

By Kate Marsden

The French Revolution of 1789 is more often connected with the birth of modern politics than with the making of modern gender roles, notwithstanding a fruitful and growing historiography on gender in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. During the Revolution attacks on religious celibacy—both male and female—consolidated stereotypes of the unnaturalness of a sexless life, uneasiness with institutions that subverted individual liberty, and critiques of the “unproductive” citizen that had been developing throughout the eighteenth century. Furthermore, under a new regime that celebrated personal liberty, perpetual religious vows were seen to violate fundamental human rights. For these reasons, despite the more pressing economic and political demands of the early revolution, the National Assembly undertook a project to dismantle France’s monasteries and “liberate” the monks and nuns they viewed as victims of Old Regime prejudices.[1]

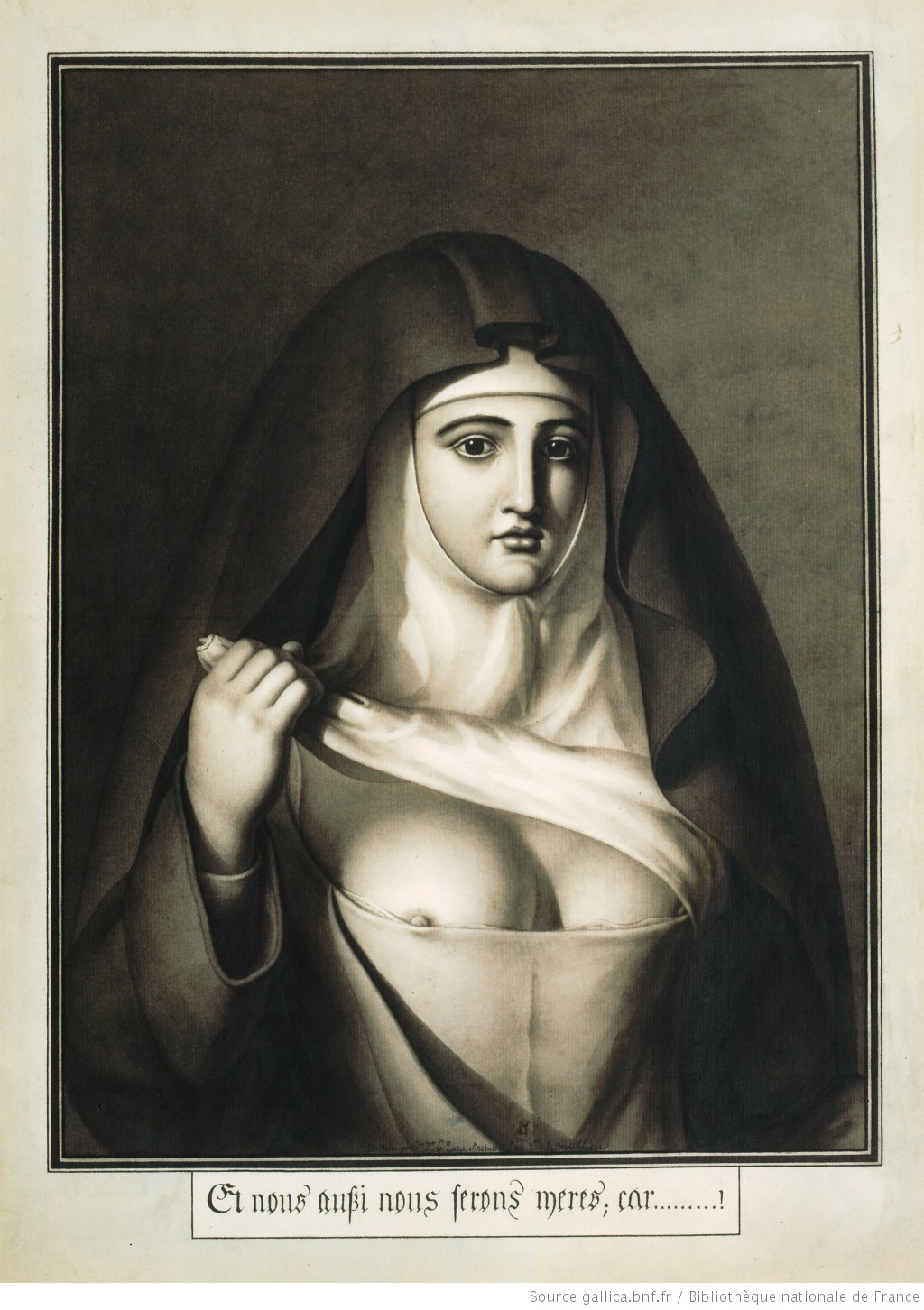

These attacks on monasticism unleashed a firestorm of debate over women’s religious vocations that bordered on obsession and seemed entirely disproportionate to the actual impact that a little over 50,000 women religious could have had on French society.[2] However, revolutionaries’ preoccupation with female celibacy is revelatory of a contemporaneous cultural and intellectual transition surrounding gender roles, marriage, and citizenship that was taking place at the end of the eighteenth century. Popular literary works of the Enlightenment, like Rousseau’s Emile, romanticized the martial partnership and condemned the parental despotism that they believed resulted in forced vocations, while underscoring woman’s biological destiny. Commentators worried about the wasted potential of the nation’s valuable human resources, unplowed and unfertilized in convents. The nature of this discourse assumed that women religious would have been better off by—and indeed receptive of—putting their bodies to the service of the nation rather than languishing behind convent walls. Louis de Jacourt’s definition of “religieuse” in the Encyclopédie lamented that nuns were “too often the victims of their parents’ luxury and vanity” and that their productive potential, economic and sexual, was “dead to the patrie.”[3] Indeed the convent came to represent the perceived decadence, luxury, and despotism of the Old Regime. The nun herself became a provocative and sexy symbol for critiquing the lost potential and wasted fertility of France, sacrificed to clerical and aristocratic urges that undermined the rights of the individual and the good of the nation. In short, the nun became a symbol of the social ills revolutionaries sought to rectify.

In abolishing religious vows and institutional celibacy, the revolution of the 1790s prescribed marriage and procreation as the duty of all citizens. As some images from the early revolution suggest, former monks and nuns were expected to be eager and willing to profit from the liberty offered by the National Assembly. As citoyens and citoyennes they were expected to marry and breed a new France, untainted by the particular interests that had defined the Old Regime.

Nevertheless, historians have long considered that the marriages of the clergy during the French Revolution were insignificant historical anecdotes simply spurred by active dechristianization efforts during the Terror from 1793-1794.[4] The number of nuns to marry has often been underestimated and the reasons for those marriages have also been simplified and misunderstood in relationship to Catholic resistance and revolutionary persecution.[5] The personal testimony of the affected clergy can be found in the Caprara archives of letters written by priests, monks and nuns to regularize their marital and religious situation after the Concordat of 1801—the peace settlement between Napoleon Bonaparte and the pope that reestablished the Catholic Church in France—provide insight into the reasons why former clergy members married during the Revolution.[6] Careful investigation of this archive suggests that the marriages of women religious were less related to active persecution and coercive practices undertaken by revolutionary dechristianizers than those of the male clergy. Rather, they were influenced by a longer-term cultural revolution of the eighteenth century that devalued monasticism and institutional celibacy at the same time that Enlightenment writers elevated and idealized the companionate partnership that men and women could find in marriage. The personal stories that former nuns recounted to Cardinal Caprara provide evidence of a cultural shift in attitudes towards celibacy and marriage that influenced former nuns’ decisions to marry during the Revolution.

In writing Cardinal Caprara, penitents were enjoined to express remorse for their breaches of clerical discipline during Revolution and encouraged to return to their former obligations. However, former nuns often phrased their requests for reintegration in the Catholic Church in surprising language. For instance, one correspondent, Jeanne Lecourtre, candidly told Caprara that she welcomed the “benevolence of the deputies [who] freed her from [her] état” as a nun. She married a soldier who “was good for her and whom she loved sincerely” and—in a bold move that could have seen her petition rejected—she asserted, “she absolutely did not regret having engaged in the bonds of marriage.”[7] Another former nun, Louise Bain stated that in her marriage she “found happiness, if happiness existed outside the bounds of religion.”[8] The fact that former nuns thought it important enough to mention in their letters to Cardinal Caprara that they had found love and happiness in their marriages implies that many former nuns accepted the popular rhetoric of companionate marriage like that found in Emile and other literary works as their own.

When trapped between sacred religious vows and familial obligations, women religious overwhelmingly chose their families. Although the Vatican wanted to see former clergy members return to their religious life, out of a sample of over 300 petitions, only three former nuns expressed their willingness to do so. Overall, the Caprara archives suggest that for many former nuns living the Revolution, love, marriage, and the companionship they found therein gave meaning to the larger upheavals they experienced during the revolutionary decade.

Revolutionaries had promoted companionate marriages based on mutual respect and affection as the basis of virtuous citizenship, and indeed in the case of former nuns this agenda was not carried out by force and compulsion, as many historians have previously believed.[9] That nuns would portray the relationships they entered outside of the convent in terms of love and personal fulfillment demonstrates the extent to which the culture of sentiment and revolutionary familial expectations had penetrated their consciousness. These personal testimonies—far from being insignificant historical anecdote—offer proof of a cultural revolution that overturned a previous sexual order which had lauded celibacy as the highest social calling in favor of new sentimental notion of marriage as a site of personal fulfillment. The Revolution established a new sexual order based on marriage as a companionate partnership defined by complementary gender roles as basis of modern citizenship and political order, thus consolidating a longer-term cultural trend of the eighteenth century.

Kate Marsden is currently a Visiting Assistant Professor at Wofford College. She’s working on a larger monograph based on her research on married nuns. Her research interests include gender, revolution, religion, and race.

Endnotes:

[1] The National Assembly decreed the suppression of solemn vows on November 2, 1789. It was not until August 18, 1792 that the complete suppression of monasteries became law.

[2] Claude Langlois, Le Catholicisme Au Féminin: Les Congrégations Françaises à Supérieure Générale Au XIXe Siècle (Paris: Cerf, 1984), 83.

[3] Jaucourt, “Religieuse,” in Encyclopedie.

[4] Albert Mathiez, “Les prêtres révolutionnaires devant le Cardinal Caprara.,” Annales Historiques de la Révolution française 3 (1926): 2.

[5] Langlois, Le Catholicisme Au Féminin, 8.

[6] Now preserved in series AF/IV 1895-1920 at the Archives Nationales in Pierrefitte-sur-Seine.

[7] AN 1907/5/25

[8] AN 1907/6/61-2

[9] Lindsay A. H. Parker, Writing the Revolution: A French Woman’s History in Letters (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Reading List:

Cage, E. Claire. Unnatural Frenchmen: The Politics of Priestly Celibacy and Marriage, 1720-1815. University of Virginia Press, 2015.

Desan, Suzanne. The Family on Trial in Revolutionary France. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

Desan, Suzanne, and Jeffrey Merrick, eds. Family, Gender, and Law in Early Modern France. Pennsylvania State Univ Pr, 2009.

Murphy, Gwénaël. Les religieuses dans la Révolution française. Paris: Bayard Centurion, 2005.

Schutte, Anne Jacobson. By Force and Fear: Taking and Breaking Monastic Vows in Early Modern Europe. Ithaca N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2011.

Tuttle, Leslie. Conceiving the Old Regime: Pronatalism and the Politics of Reproduction in Early Modern France. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

“The Revolution established a new sexual order based on marriage as a companionate partnership defined by complementary gender roles as basis of modern citizenship and political order,….”. So basically the idea that men and women, although not equal, are equivalent; team mates in the family dynamic.

LikeLike