By Jeffrey Ostler

Sometime in mid-1776, just as colonists were declaring their independence from Great Britain, an unnamed Shawnee addressed an assembly of representatives from multiple Indigenous nations who had gathered at the Cherokee capital of Chota. Taking a wampum belt in hand, the Shawnee spoke of a long history of injustice at the hands of the “Virginians,” a term many Native people applied to greedy settlers from Virginia and other colonies. The “red people,” he said, had once been “Masters of the whole Country,” but now they “hardly possessed ground enough to stand on.”[1] Not only did the Virginians want their land, the Shawnee contended, they wanted their lives. It is “plain,” he said, that “there was an intention to extirpate them.”[2] Although the term genocide had not been invented, this is precisely what the Shawnee feared Native people were up against: a project that threatened their very existence.[3]

Since the publication of Bernard Bailyn’s introduction to Pamphlets of the American Revolution in 1965, we have known that colonists expressed fears of a British conspiracy to enslave them.[4] Yet we have paid little attention to Native American fears that colonists intended to annihilate them. How widespread were these fears? As I was researching my recent book, Surviving Genocide, I found several examples of what I call “an Indigenous consciousness of genocide.”[5] In March 1776, for example, a Cherokee leader named Dragging Canoe told a British agent that his nation “had but a small spot of ground left to stand upon” and that the colonists’ unrelenting demands for land proved that it was their “Intention…to destroy [the Cherokees] from being a people.” Three years later, as the Continental Army was about to invade Iroquoia, the homeland of the Six Nations (Haudenosaunees), Mohawk leader Joseph Brant wrote of his “determination to fight the Bostonians,” another designation for rapacious colonists, observing that “it is their intention to exterminate the people of the Longhouse.”[6]

I also discovered that U.S. officials were well aware that Native people were making allegations like those of Dragging Canoe and Joseph Brant. Evidence of their knowledge was sitting in plain sight in the first written treaty between the United States and an Indian nation—the 1778 Fort Pitt Treaty with the Delaware Nation. Article 6 of the treaty addresses the charge that “it is the design of the [United] States…to extirpate the Indians and take possession of their country.” The text, which U.S. commissioners wrote, attributes this allegation to the “enemies of the United States” (i.e., the British), who “have endeavored by every artifice in their power” to convince the Indians of this “false suggestion,” as if Native people wouldn’t have arrived at this conclusion on their own. To convince the Delawares of U.S. benevolence, the treaty promises to guarantee Delaware rights to their lands and offers to consider creating a fourteenth state for Indians.[7] Historians have long been fascinated with the idea of an Indian state (an idea which politicians and reformers occasionally proposed into the early twentieth century) without noticing that U.S. leaders first raised the possibility to counter allegations of genocide.[8]

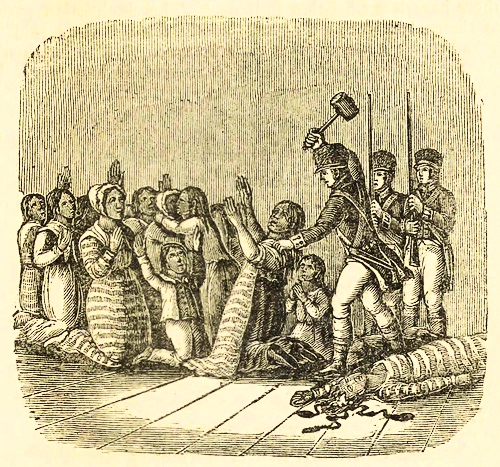

Much that occurred during the Revolutionary War supported Indigenous perceptions of the new American nation’s genocidal intentions. From 1776 to 1783 the United States and state militias conducted close to a dozen military operations against Native nations. The most well-known of these was the 1779 Clinton-Sullivan expedition which invaded Iroquoia (homelands of the Haudenosaunees in New York), though there were many others. As U.S. troops and state militias targeted Indian towns, they killed several hundred defenders and inhabitants and raped girls and women. Losses from direct killing and abuse of captured women would have been much higher had not Native people abandoned their towns, leaving the graves of their ancestors to be robbed, and their houses and crops to be torched. From 1776 to 1783, U.S. troops destroyed over seventy Cherokee towns, fifty Haudenosaunee towns, and at least ten multi-ethnic towns in the Ohio Valley. The cost of this destruction was high, subjecting people to starvation and disease, and in some cases causing leaders to relocate to new places, but for many communities the strategy of abandoning towns seemed the only way to avoid being slaughtered. As Seneca chief Sayengeraghta (Old Smoke) later said, “We lost our Country it is true, but this was to secure our Women & Children.”[9] Haudenosaunees and other nations had not been completely annihilated, but from their perspective this was not because the new United States and its people did not intend to exterminate them. Instead, their own agency had prevented an even worse catastrophe.

After the Revolutionary War was over, Samson Occom, a Mohegan Christian, wrote that it “has been the most destructive to poor Indians of any wars that ever happened in my day.”[10] Although Indians had survived, the war left a legacy of fear. In 1790, when the Seneca leader Cornplanter visited George Washington in the new nation’s capital of Philadelphia, he informed the President that when “your army entered the country of the Six Nations, we called you the town destroyer; and to this day, when that name is hard, our women look behind them and turn pale, and our children cling close to the necks of their mothers.”[11] In a catalog of horrific events, one stood above all others in the memories of Native people as proof of American intentions. This was the Gnadenhütten massacre of 1782, when a Pennsylvania militia slaughtered ninety-six unarmed Delawares who converted to Christianity under the guidance of Moravian missionaries. In the late 1780s, when portions of several Native nations formed a confederacy to defend their lands against the new United States, they cited the time the Americans “did kill upwards of one hundred of our People, who never took up a single Weapon against them but remained quiet at home, planting Corn and Vegetables” as evidence for the proposition that Americans would not be satisfied until “they have extirpated us entirely; and have the whole of our Land!”[12] Perhaps Indigenous peoples’ worst fears of 1776 had not been fully realized, but the colonists’ victory over the British Empire meant that the possibility of complete and total annihilation remained very much alive.

If it is true that revolutions are conceived in fear and produce terror, then it is no surprise that fear was everywhere during the American Revolution. Some fears, like those of colonists that the Crown might enslave them, even if contextualized as a metaphor for a political condition, are justly subject to ridicule and were mocked at the time. As Bailyn noted, Loyalists readily exposed the hypocrisy of the advocates of independence for “ground[ing] their rebellions on the ‘immutable laws of nature’ and yet…themselves owned two thousand Negro slaves.”[13] But the other fear of rebel enslavers—that their property would rise up against them—was very real, as were the fears of Loyalist enslavers that Patriots would confiscate their human, along with their non-human, possessions. These fears, or those of white settlers who were terrified of the “merciless Indian savages” that Thomas Jefferson conjured in the Declaration of Independence, may not elicit much sympathy today.[14] We are far more likely to empathize with ordinary soldiers trembling before death, and their loved ones at home praying desperately for their return. Nonetheless, the fear expressed by the unnamed Shawnee at Chota in 1776 was unique. Native people faced something no one else did—that their communities, their nations, the “red people” in their entirety might someday cease to exist. No one else had to confront the challenge of surviving genocide.

At one time, historians of the American Revolution paid little attention to American Indians. Fortunately, this is no longer true, as an excellent series of essays on “Native American Revolutions” published on this website in 2017 makes clear. These essays reveal that current scholars are less interested in the destructive effects of the Revolution on Native communities than in highlighting the agency of Native people, sometimes as autonomous actors, sometimes shaping the course of events, sometimes adapting to and surviving through revolutionary upheavals.[15] This is all to the good. Nonetheless, our account of Native American Revolutions is incomplete without realizing that many Native people perceived colonists and the new nation they created as an existential threat. A recognition of an Indigenous consciousness of genocide provides a fuller account of Native perspectives in a revolutionary era, or, to borrow Daniel Richter’s phrase, of what it meant to “face east from Indian country.”[16] It also asks us to think more critically about the American Revolution’s implications for Native communities. It may be unsettling to consider the creation of the United States as a genocidal project, but the experiences of many of eastern North America’s Indigenous people led them to think of it in precisely this way. Examining their reasons does not necessarily mandate agreement with their conclusion, but it does ask us to take their fears more seriously than we have.

Jeffrey Ostler is Beekman Professor of Northwest and Pacific History at the University of Oregon. He is the author of The Plains Sioux and U.S. Colonialism from Lewis and Clark to Wounded Knee (2009), and Surviving Genocide: Native Nations and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas (2019). He can be reached at jostler@uoregon.edu.

Title image: Burning of Coreorgonel by Colonel Dearborn, September 24, 1779.

Further Readings:

Calloway, Colin G. The Indian World of George Washington: The First President, The First Americans, and the Birth of the Nation. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

DuVal, Kathleen. Independence Lost: Lives on the Edge of the American Revolution. New York: Random House, 2015.

Fullagar, Kate and Michael A. McDonnell, eds. Facing Empire: Indigenous Experiences of Empire in a Revolutionary Age. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018.

Pearsall, Sarah M. S. “Recentering Indian Women in the American Revolution.” In Why You Can’t Teach United States History without Indians, ed. Susan Sleeper-Smith, et al., 57-70. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Endnotes:

[1] William L. Saunders, ed., The Colonial Records of North Carolina, vol. 10 (Raleigh, N.C.: Josephus Daniels, 1890), 778.

[2] Ibid.

[3] The term genocide was coined in 1944 by the Polish jurist Rafael Lemkin in Axis Rule in Occupied Europe (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1944).

[4] Bernard Bailyn, “General Introduction: The Transforming Radicalism of the American Revolution,” in Pamphlets of the American Revolution, vol. 1, ed. Bailyn (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1965), 74, 86-89, 140-42.

[5] Jeffrey Ostler, Surviving Genocide: Native Nations and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2019); Ostler, “‘To Extirpate the Indians’: An Indigenous Consciousness of Genocide in the Ohio Valley and Lower Great Lakes, 1750s-1810,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., vol. 72, no. 4 (October 2015): 587-622.

[6] Saunders, ed., Colonial Records of North Carolina, vol. 10: 764; Francis Whiting Halsey, The Old New York Frontier: Its Wars with Tories, Its Missionary Schools, Pioneers and Land Titles, 1614-1800 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901), 279.

[7] Charles J. Kappler, ed., Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, Vol. 2: Treaties (Washington, D.C.: G.P.O., 1904), 4.

[8] For an overview of proposals for an Indian state, see See Annie H. Abel, “Proposals for an Indian State, 1778–1878,” in Annual Report of the American Historical Association for the Year 1907 (Washington, D.C., 1908), 1: 89–102.

[9] Adam Hubley, “Journal of Lieut.-Col. Adam Hubley,” in Journals of the Military Expedition of Major General John Sullivan against the Six Nations of Indians in 1779, comp. Frederick Cook (Auburn, N.Y.: Knapp, Peck & Thomson, 1887), 157-58.

[10] Quoted in David J. Silverman, Red Brethren: The Brothertown and Stockbridge Indians and the Problem of Race in Early America (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2010), 108.

[11] American State Papers: Indian Affairs, 1:140.

[12] John Heckewelder, Narrative of the Mission of the United Brethren among the Delaware and Mohegan Indians from Its Commencement in the Year 1740 to the Close of the year 1808 (Philadelphia: McCarty & Davis, 1820), 381, 383. For the Moravian missions, see Jane T. Merritt, At the Crossroads: Indians and Empires on a Mid-Atlantic Frontier, 1700-1763 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 70-76, 95-121. For a recent account of the Gnadenhütten massacre, see Rob Harper, Unsettling the West: Violence and State Building in the Ohio Valley (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018), 136-142.

[13] Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1967), 241.

[14] For Jefferson’s drafting of this phrase, see Anthony F. C. Wallace, Jefferson and the Indians: The Tragic Fate of the First Americans (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999), 55-57.

[15] The first major study of Native Americans and the Revolution was Colin G. Calloway, The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995). For the Native American Revolutions series, see https://ageofrevolutions.com/2017/10/16/native-american-revolution/.

[16] Daniel K. Richter, Facing East from Indian Country (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2001).

I appreciate the info on Native Americans History something not taught in schools .

LikeLike