By Lindsay M. Chervinsky

George Washington wrote to his close friend, Henry Knox, on April 1, 1789, as he prepared to leave his beloved Mount Vernon for New York City to be sworn in as the first President of the United States. Washington confided in Knox “that my movements to the chair of Government will be accompanied with feelings not unlike those of a culprit who is going to the place of his execution.”[1]

Washington knew the public would scrutinize his every action and the smallest choice would set executive precedent. Other elected and appointed officials shared Washington’s anxieties about the pressures facing the first federal administration. They looked to the new Constitution for direction and referred to their own experience for guidance. Congressmen and executive officials drew from state government practices established during the American Revolution. Washington also relied on his revolutionary experience as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army. As President, he employed many of the same leadership tactics that he first utilized during the Revolutionary War: he organized his social interactions based on increasing levels of intimacy; he looked to military tradition to guide his interactions with the Senate; and he adopted council of war practices when he created the first presidential cabinet. Washington’s reliance on his Revolutionary War experience ensured that the American Revolution shaped the development of the executive branch long after the Treaty of Paris ended the war on April 15, 1783.

First, Washington created a tiered social scene to control his interactions with the public and to provide private opportunities for conversation. As Commander-in-Chief, Washington operated within the first tier when he hosted dignitaries and government officials at public events. The second tier occurred when he gathered with select visitors, officers, and their families at daily lunches at his headquarters in Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. The most private social tier took place when Washington gathered his aides for a private nightly supper. As President, Washington mimicked the social organization he employed during the war. He greeted guests at weekly public levees. Martha Washington’s weekly drawing-room gatherings relieved Washington of hosting responsibilities and allowed him to mingle with attendees and engage in conversation about business or politics. Finally, the Washingtons welcomed select guests to private family dinners.[2]

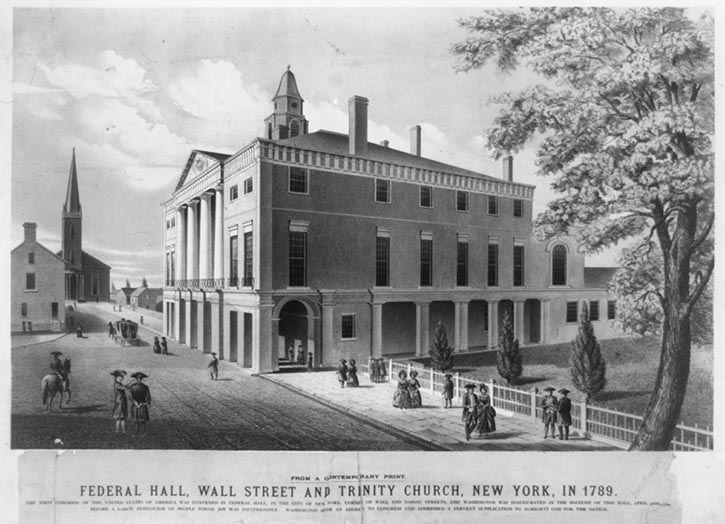

Second, as he forged a relationship with the Senate, Washington initially expected the Senators to readily provide advice as his officers has done during the Revolutionary War. On August 21, 1789, Washington arrived at the Senate Chambers in Federal Hall on Wall Street. He wished to discuss an upcoming summit between representatives from the federal government, North Carolina, and the Creek peoples. Prior to his arrival on the twenty-first, Washington shared with the Senate all previous treaties between the U.S. and the Native Americans. Washington also brought along Secretary of War Henry Knox to answer any questions. As the Secretary of War under the Confederation government, Knox possessed extensive knowledge about the tense relationship between the U.S. and the Creeks. On the day of his visit, Washington presented a list of questions to the Senate. Washington borrowed this practice from military tradition. He frequently presented questions to his officers at councils of war and expected prompt answers. After Washington shared his questions with the Senate, however, the Senators sat in awkward silence. The Senate eventually voted to refer the questions to a committee for further examination. Washington agreed to return the following Monday for their recommendation, but not before angrily expressing his displeasure at the delay.[3] On his way out of Federal Hall, he reportedly swore never to return to the Senate for advice and he kept his word.

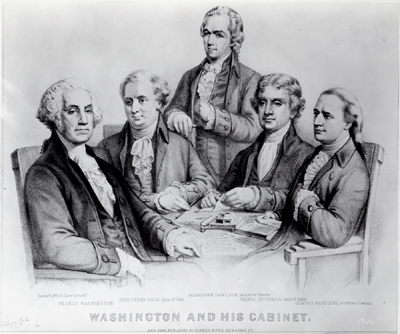

Washington prized the efficiency of councils of war, and the Senate’s reliance on committee deliberation rendered it unsuitable to provide the President with timely advice. Instead, Washington slowly and deliberately moved towards the creation of the cabinet. Cabinet practice crystallized as a central feature of the executive branch during the Neutrality Crisis in April 1793. Faced with the possibility of war with both France and Great Britain, Washington convened regular cabinet meetings to address the diplomatic crisis.[4] The first cabinet included Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, Secretary of War Henry Knox, and Attorney General Edmund Randolph.

Finally, as Washington created the cabinet to meet the demands of governing, he adopted many council of war practices. He convened both councils of war and cabinet meetings at his pleasure and with relatively little notice. He also frequently submitted questions to the participants for their consideration in advance of the meeting.[5] Unlike the relatively large Senate, Washington’s officers and the department secretaries offered opinions immediately. If the council or cabinet meeting failed to reach a consensus, Washington requested follow-up written opinions. The cabinet also served as Washington’s official family, just like his aides-de-camp and officers during the war. He included them in private dinners and social activities outside of their professional engagements.[6]

Many scholars have evaluated how state legislative practices influenced the First Federal Congress and congressional behavior after 1789. The relationship between Washington’s revolutionary experience and his presidency demonstrates that the American Revolution shaped the development of the new federal government, especially the executive branch, long after the end of the war.

Lindsay M. Chervinsky is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of California, Davis. Her dissertation focuses on the military, state, and British origins of the President’s cabinet in George Washington’s administration. You can reach her at lindsay.chervinsky@gmail.com or on Twitter at @lmchervinsky.

Title image: George Washington cigar label, n.d.

[1] George Washington Henry Knox, 1 April 1789. The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, ed. Dorothy Twohig (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1987), 2: 2-3.

[2] Arthur S. Lefkowitz, George Washington’s Indispensable Men, (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003), 74-76. Amy Hudson Henderson, “Furnishing the Republican Court: Building and Decorating Philadelphia Homes, 1790-1800” (PhD diss., University of Delaware, 2008), 66-77.

[3] William Maclay, The Diary of William Maclay, ed. Kenneth R. Bowling and Helen E. Veit (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988), 128-129.

[4] “Cabinet Opinion on the Recall of Edmond Genet, 23 August 1793,” The Papers of George Washington Presidential Series, 13: 530-531n.

[5] George Washington to General Officers, 26 October 1777. The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, ed. Harold C. Syrett (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), 1: 345-346. George Washington to the Cabinet, 18 April, 1793, The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, 12: 452-454.

[6] George Washington, “October 1789,” The Diaries of George Washington, ed. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1979), 5: 448-488.

Further Readings

Bowling, Kenneth R. The Politics of the First Congress, 1789-1791. New York, Garland, 1990.

Freeman, Joanne B. Affairs of Honor. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.

Higginbotham, Don. “Washington and the Colonial Military Tradition,” in George Washington Reconsidered, ed. Don Higginbotham. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2001.

Lengel, Edward G. General George Washington. New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2005.

Greetings! I’ve been following your website for a while now and finally got the bravery to go ahead and give you a shout out from Austin Texas! Just wanted to say keep up the excellent job!

LikeLike