This post is a part of our “Faith in Revolution” series, which explores the ways that religious ideologies and communities shaped the revolutionary era. Check out the entire series.

By Glauco Schettini

“Today is the day,” an alarmed Dionigi Strocchi wrote on September 17, 1796 to a friend in Faenza, in the north of Italy. In Rome, where Strocchi worked as a secretary of the College of Cardinals, “everyone [was] murmuring about a holy war, a war of religion” soon to be waged against revolutionary France. Its consequences, Strocchi anticipated, would be ruinous.[1] Strocchi’s fears were not misplaced. After Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of the Papal States in June, papal and French delegates had signed an armistice in Bologna, but peace talks, which had started in Florence early in September, were stalling. To Strocchi’s great dismay, Austrian and Neapolitan diplomats were urging Pope Pius VI to quit the negotiating table and launch a crusade against France, an option that was receiving increasing support in the papal entourage, as well.

The day Strocchi feared never came. And yet, the prospect of a crusade against France was more than the late-summer dream of a papal Curia suddenly realizing Rome was no longer a safe haven. Catholic thinkers throughout Europe had long been pondering how to respond to the French Revolution, especially to what they regarded as the Revolution’s most frightful feature—the secularizing thrust—which the French armies were now exporting throughout the continent. The idea of a counterrevolutionary crusade seemed to many a fitting response. The war the French were fighting, as Catholic intellectuals saw it, was a total war—an ideological war and a war of annihilation.[2] A crusade would match the French’s ideological commitment, as it would not be just a defensive war but a war meant to uphold a world order radically alternative to the revolutionary one. And it would also encourage the active involvement of popular masses in the fight—an adequate response to France’s mass levy.

It did not take long before Catholic counterrevolutionary intellectuals started depicting the Revolution as an outright attack on Catholicism. Counter-Enlightenment thinkers had long been accustomed to regard eighteenth-century culture as disruptive of traditional beliefs. When the Revolution came, its opponents just had to graft their criticism of France’s policies onto this tradition of thought. And as military conflict broke out between supporters and opponents of the Revolution, both within and beyond France’s borders, religion turned out to be an effective rallying cry. Counterrevolutionary insurgents in France branded themselves as the Catholic and Royal Armies and adopted the Sacred Heart as their symbol. Outside of France, too, clerics actively supported the military efforts of their compatriots.

It was the Spanish clerics who most thoroughly described the ongoing conflict as a war of religion. When France declared war on Spain in March 1793, Spanish clerics seized upon existing counterrevolutionary tropes and weaved them into a coherent rationale for war. For almost two years, sermons and pastoral letters provided a formidable sounding board for its propagation. In these works, the French were invariably portrayed as the enemies of religion—apostates who had “abolished every sacred ceremony and ruined churches and altars,” for Bishop Lorenzana of Girona.[3] As the French sought to destroy religion, there could be no doubt, claimed Carmelite preacher Nicolás Chornet, that the Spaniards were fighting “a holy war, a war of religion, which can be characterized with the sacred name of war of God.”[4] Such a war could draw strength from Spain’s long-established Catholic tradition, and especially from its tradition of religious warfare. Numerous were the references to the Reconquista, the long war against the Muslim kingdoms of Spain, which was increasingly coming to be seen as the foundational moment of Spanish national identity. Archbishop Lezo of Zaragoza, among others, exhorted his compatriots to fight against the French “as you fought to reestablish our sacred religion and our monarchy” when “the Arabs defiled our temples.”[5] And as they defended religion, the Spaniards were also fighting for the public order and the good of the state—three terms that were essentially interrelated, as religion was assumed to be the foundation of the existing social and political system. The clergy’s involvement in such fight was certainly the product of sheer concern, but clerics were also seizing a chance to reassert their capacity for moral and political leadership. As they made the defense of religion central to Spain’s war effort, they were claiming for themselves a directive role in the post-revolutionary world.

The Spanish clergy, then, extensively described the war against France as war of religion, in which the very survival of Catholicism, and of the country, was at stake. Such a war required the energies of the whole nation and the complete dedication of the soldiers, whom God would certainly reward for their sacrifices. There was perhaps no work where all these themes were more fully expounded than El soldado católico en guerra de religión by Diego de Cádiz, a Capuchin friar and a preacher of great renown. “Every good son of the holy church,” he wrote, “must take up arms to defend it from its opponents and enemies.”[6] However, not even he went as far as to describe the war as an actual crusade. The power to launch a crusade rested with the Pope. Thus, it was up to someone who could expect to exert a more direct influence on Pius VI to call for a crusade against France.

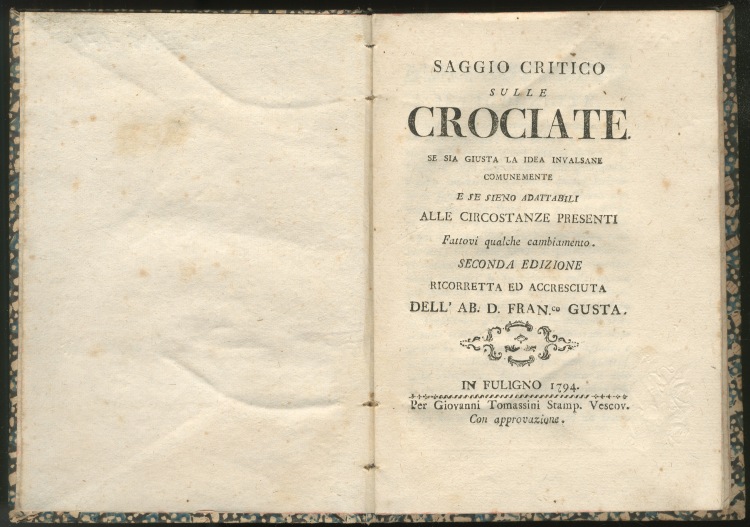

This someone was Francisco Gustá, born in Barcelona in 1744. After entering the Jesuit order, he left Spain when the Jesuits were expelled in 1767, and was struck by the order’s suppression in 1773. He found shelter in the Papal States, and rapidly became a famous polemicist, well-known for his works against the religious reforms of sovereigns such as Emperor Joseph II of Austria and Grand duke Peter Leopold of Tuscany, and against their Catholic supporters, especially the Jansenists. When the French Revolution broke out, he soon joined his fellow Catholic apologists who argued that the Revolution was the product of a plot hatched by Jansenists, philosophes, and freemasons. Most importantly, as he provided a diagnosis of the causes of the Revolution, he also set out to explain how to deal with its consequences; and for this purpose he wrote his Saggio critico sulle crociate (1794).

In the Saggio, Gustá explained how to adapt the model of medieval crusades to the needs of the modern era. The crusades, he argued, had been the product of the “remarkable agreement of religion and politics” in a period when religious and political authorities cooperated harmoniously, and more specifically, religious figures—and ultimately the pope—determined the goals that political powers had to pursue.[7] A crusade “adapted to the present circumstances,” as the Saggio’s subtitle read, would resurrect such an arrangement. But medieval crusades also offered a blueprint for the war against France. France’s mass levy, Gustá noted, had ushered in a new era of warfare. The professional armies of the Old Regime were unsuited for the people’s war the Revolution had launched. The only credible response to France’s mass levy was a modern crusade in which the masses would enlist out of their profound religious devotion. “Religion,” Gustá argued, “is the most powerful incitement for the peoples to take up arms willingly and courageously.”[8] Thus, instead of opposing the sudden irruption of the masses onto the political scene, Catholics should welcome it—and channel it toward the renewal of the cooperation of church and state.

No anti-French crusade was ever launched, but Gustá’s Saggio was widely read and repeatedly reprinted in the following years. Most importantly, it highlighted the extent to which the Age of Revolutions paved the way for a sweeping reinvention of Catholicism. The war against France led Catholics to call for a reframing of the relationships between religion and politics based on the model of medieval Christendom. This model was certainly idealized, but to its supporters, it essentially meant the Church’s traditional legal privileges had to be restored, and that the ecclesiastical hierarchies had to set the goals that political powers would pursue. The Church—and ultimately its leader, the Pope—should lead the international community, so as to heal the wounds produced by revolutionary secularization and enlightened absolutism. However, even though the world of the Catholic counterrevolutionaries was a world that looked at the Middle Ages as its ideal model, appeals for a crusade also implied the need to embrace perhaps the most radical consequence of the Revolution—the sudden irruption of the masses onto the stage of politics. Though in an unsystematic fashion, eighteenth-century crusaders outlined the defining characteristics of nineteenth-century Catholicism: its medievalist ideals, and its drive toward the creation of a mass-based Catholic movement.

Glauco Schettini is a PhD candidate in modern European history at Fordham University and is currently working on a dissertation on the intellectual history of Catholicism in the age of revolutions. His most recent publications include “Confessional Modernity: Nicola Spedalieri, the Catholic Church and the French Revolution, c.1775-1800,” Modern Intellectual History (2019).

Title image: Cardinal Fabrizio Ruffo leading the Sanfedisti in 1799, protected by Saint Anthony

Further Reading:

Bell, David A. The First Total War: Napoleon’s Europe and the Birth of Warfare as We Know It. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2007.

Carl, Horst. “Religion and the Experience of War: A Comparative Approach to Belgium, the Netherlands and the Rhineland.” In Soldiers, Citizens and Civilians: Experiences and Perceptions of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1790-1820, edited by Alan Forrest, Karen Hagemann, and Jane Rendall, 222-42. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Herr, Richard. The Eighteenth-Century Revolution in Spain. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1958.

McMahon, Darrin M. Enemies of the Enlightenment: The French Counter-Enlightenment and the Making of Modernity. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Serna, Pierre, Antonino De Francesco, and Judith A. Miller, eds. Republics at War, 1776-1840: Revolutions, Conflicts, and Geopolitics in Europe and the Atlantic World. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Endnotes:

[1] Giovanni Ghinassi, ed., Lettere edite ed inedite del cavaliere Dionigi Strocchi ed altre inedite a lui scritte da uomini illustri, vol. 1 (Faenza: Conti, 1868), 55. All translations are mine.

[2] See David A. Bell, The First Total War: Napoleon’s Europe and the Birth of Warfare as We Know It (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2007).

[3] “Edicto del ilustrísimo señor obispo de Gerona,” Semanario de Salamanca, 16 December 1794, 178.

[4] Nicolás Chornet y Año, Medio seguro para triunfar de la Francia: Oración deprecatoria y ascetica (Valencia: Burguete, 1794), 30.

[5] “Carta pastoral del ilustrísimo señor arzobispo de Zaragoza,” Semanario de Salamanca, 2 September 1794, 166.

[6] Diego José de Cádiz, El soldado católico en guerra de religión: Carta instructiva ascetico-historico-politica, vol. 1 (Ecija: Daza, 1794), 7.

[7] Francisco Gustá, Saggio critico sulle crociate: Se sia giusta la idea invalsane comunemente e se sieno adattabili alle circostanze presenti, fattovi qualche cambiamento (Ferrara: Rinaldi, 1794), 33.

[8] Ibid., 100.