By Olatunde Taiwo

This article is part of our series entitled “Exiled: Identity and Identification,” which explores the semantic evolution of exile and the lived experiences of people seeking refuge across the Atlantic World during the long nineteenth century. It was presented originally at the conference “Who is a Refugee? Concepts of Exile, Refuge and Asylum, c.1750-1850”, which took place on 30 June – 1 July 2022 at the University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany.

This publication is part of a project that has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 849189).

Very few regions in the world experienced the magnitude of revolutionary upheaval that unfolded in the Nigerian area of the nineteenth century.[1] Indeed, at the heart of all these were forces such as the 1803-Uthman Dan Fodio Jihad of northern Nigeria, the disintegration of the Old Oyo Empire between 1800 and 1833, the enforcement of the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade and its replacement by ‘Legitimate Commerce’ from 1807, and the 1833 onset of the Yoruba civil wars including the hordes of refugees and asylum-seekers unleashed by them. This essay examines the intersection of refugees, asylum-seekers, and deportation in the history of this area between 1800 and 1852.

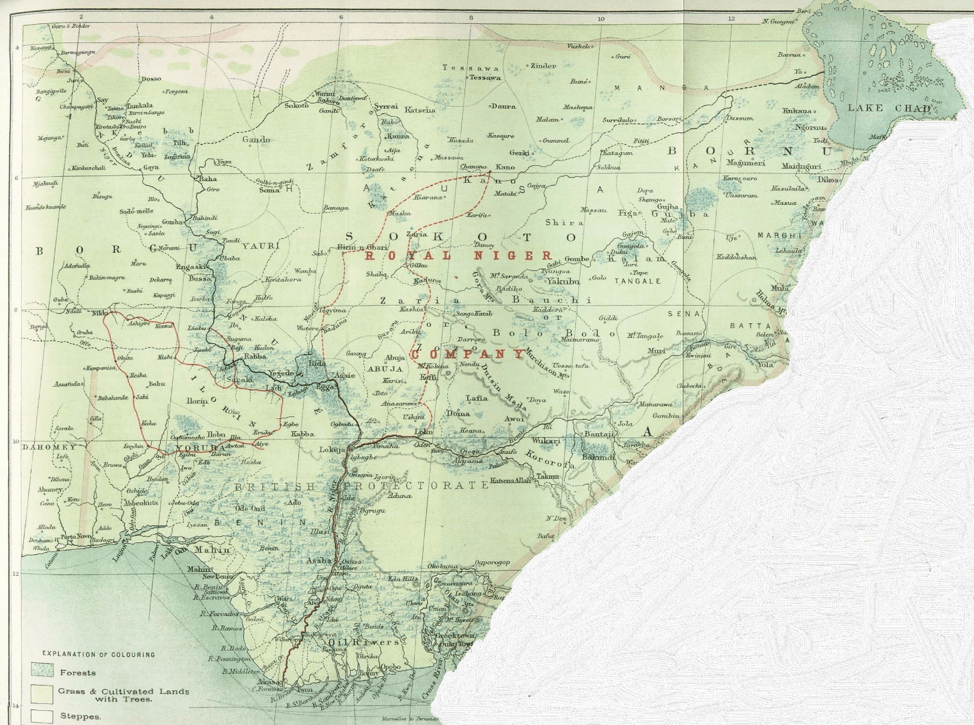

To fully understand how deportation, asylum, and refuge were mutually constituted in nineteenth-century Nigeria, it is important to recognize that the region was inhabited by roughly 300 ethno-linguistic groups divided into hundreds of centralized and decentralized states. They included the Yoruba-dominated states of Old Oyo, Ijebu, Ijaye, Ibadan, and Abeokuta, the Kanuri and Hausa in Borno, the Edo in Benin, the Nupe in Nupeland, the Itsekiri in Aboh, and the Ijaw in Nembe, Opobo, Bonny, and Okrika. The Fulani and Hausa-dominated populated polities of Sokoto, Ilorin, Gwandu, Jamare, Gaura, Katsina, Kano, Kazaure, Zaria, Kotangora, Nupe, Misau, Hedejia, Katagum, Gombe, Bauchi, Fombia, and Lapai also numbered among these states.[2]

Nigeria in 1896. The locations of some of these states are written in 3 sizes of black ink within the map. The Rev. Ch. H. Robinson M.A. (1896) Hausaland, Scottish Geographical Magazine.

In addition, it is worth noting that some of these states-like Ibadan, Abeokuta, and emirates of the Sokoto Caliphate emerged from the displacements, instability, wars, and crises that followed the Uthman Dan Fodio Jihad of 1803 and the collapse of the Old Oyo Empire in 1835. These new states became multiethnic, attracting peoples seeking refuge and asylum far from the hotspots of the crises. Yet, asylum into the period’s old and new states was commonly an outcome and feature of deportation as well.

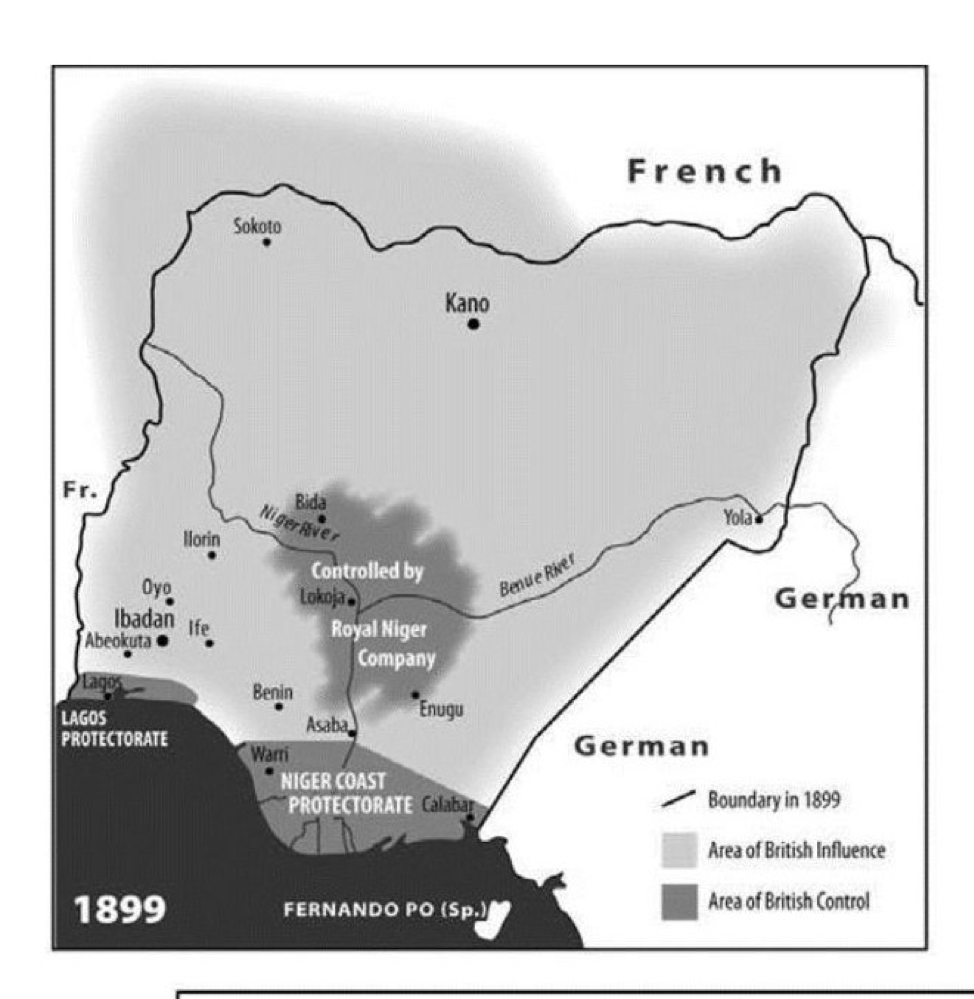

Nigeria at the onset of full-scale colonization. From Toyin Falola and Matthew Heaton, A History of Nigeria,(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 94.

Deportation of this kind is traceable to periods before the 1800s in the Nigerian area. As early as 1651, for example, the King of the Benin Empire expelled some Europeans, forcing them to seek refuge elsewhere. Jacob Ade Ajayi poignantly captures this, writing “In the middle of the seventeenth century, Spanish and Italian Capuchins made a determined effort” to proselytize Benin. ‘They were given rooms in the palace, but denied free access to the Oba (King)…and when in August 1651 they tried to disturb a religious festival involving human sacrifice, they were thrust out by an angry mob and subsequently deported.”[3] There is equally evidence of asylum-constituted deportation in the operations of the Oro cult among many of the seventeenth -nineteenth-century Yoruba states.[4] The Oro cult performed several functions in each of these Yoruba states, including the deportation of persons who committed grim offences. This is apparently because deportation, including forced asylum, was worse than death in the world of any Yoruba person of that period.[5] And the indigenous head of Ibadan in 1939 underscores this. In his words, for the Yoruba, in the nineteenth century, “a man of rank who falls into political disgrace would prefer to “go and sleep(die) instead of facing the ordeal of being deported from his home and town.”[6] Underlining this point further, Olumide Lucas states, in “ceremony for banishment…of a criminal or unwanted person. The house of the person concerned is surrounded by the members of the Oro…The person is then arrested and carried away into the bush either for banishment or for execution.”[7]

Nineteenth-century Yoruba oral tradition likewise provides further evidence of asylum-attended deportations. Here, Lamurudu and his siblings’ mythical expulsions and the banishment of Sango, the fourth Alaafin of Oyo, are two cases that historians frequently recounted.[8] Similarly, Lagos oral tradition indicates that between 1704 and 1760, Gbobaro, the reigning King of Eko (Lagos), deported Akinsemoyin, a future king of Lagos, to Badagry, which became the polity of temporary asylum of the latter.[9] Meanwhile, this tradition also mentions the deportation of such Lagos monarchs as Adele Ajosu and Idewu Ojulari between 1775 and 1810.

Indeed, before and throughout 1800 to 1850, expulsions of mothers of newly born twins constituted a distinct layer of deportation within many Igbo polities. For those that survived the enforcement of the deportation, asylum came in the form of distant polities. Relatedly, asylum-attended deportation was the penalty for adultery among the Mmako, as in several other Igbo sub- groups. Meanwhile, in the incidence of adultery by any of the monarchs’ wives, the culprit, as an alternative to losing her head, self-deported, or was deported- with her young children – to another Ekiti kingdom, where the ‘culprits’ remained as refugees for the rest of their lives. Invariably, until the British colonization of the Ekiti in the 1890s, there is little evidence that this ceased to be the practice. Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that the permanence of asylum-generating deportation was not uniform for all the polities of the Nigerian area between 1700 and 1850. Evidence exists of Irigwe acephalous communities that had a tradition of “temporary banishment” out of a village for the crime of murder.[10]

When taken together, it becomes clear that deportation, including asylum-constituted deportation, was used by the peoples of Nigeria before 1800 and even after to preserve aspects of their mores, norms, and values.

Ajisafe Moore’s research uncovers the close link between deportation and asylum in the Ekiti and other Yoruba polities from 1800 to 1850. He reveals that crimes like larceny, burglary, and treason were met with severe punishments such as death, expulsion, or deportation upon the offender and the offender’s children atimes.”[11] He adds: “To every title is attached…special…powers, not [to]be…abused…Should anyone holding a title neglect to do his duty he is liable to heavy fine …deprivation of the title…should it be a capital offence, his house may be razed…and himself expelled during the king’s pleasure.”[12] This, remarkably, is consistent with Johnson’s observation, that “total banishment”, accompanied by asylum and refuge-seeking was imposed on Yoruba people found to be involved in an incestuous relationship.[13] Murray Last also confirms what the previously mentioned point on how many 1800-1852 Nigerian polities comprised of refugees who were exiled or deported. In his words: “Political life within these Zamfara and Burmi communities was unstable….the area off a state and its strength were corelative. As there were numerous refugees exiled from neighbouring states, the opportunities for subversion were many.”[14]

The deportation of Muhamaddu Nigilliroma, the 58th Mai of the Borno Empire, in 1814, and the subsequent expulsion of Oba Idewu Ojulari from Lagos due to succession feuds between 1815 and 1819, illustrate how deportation practices that necessitated the need for asylum continued to persist in Nigeria from 1800 to 1850.[15] The same can be said for the deportations of Prince Oshinlokun and King Adele of Lagos in 1816 and 1821 respectively, which were fueled by the entrenched succession and dynastic feuds of the time.[16] It is worth noting that Zofun, the Akran -King – of Badagry, was also banished around 1821, although it is unclear where he sought asylum and refuge.[17]

The deportation and transformation of Mallam Dendo Manko and his followers from Raba/Nupeland, to asylees in Ilorin during the 1820s is also a significant here.[18] And behind these deportations was the presiding Nupe monarch, Majiya. Two of Dendo’s sons also suffered the same fate twenty years later. Usman Zaki Dendo, who was the King of Nupeland for some time, and his son Umaru were the first to be expelled to asylum in Kebbi in 1841.[19] Masaba Dendo was deported next in 1847, after a revolt by his lieutenant, Umar Bahaushe. Another example of the apparent resort to asylum arising from deportation in this area was the deportation of the third emir, Mallam Musa, of the Jama’a emirate, around 1840 by the Emir of Zaria, the superordinate emirate over the Jama’a.[20]

Remarkably, in early 1840, power plays, court intrigues, and political self-preservation were precipitating another asylum-producing deportation south of Nupeland. This deportation ultimately culminated in the expulsion of Ibadan’s most intrepid General, Chief Elepo, by Ibadan’s leader, Basorun Oluyole, because of the Osogbo War between Ilorin and Ibadan.[21]

Yet, pre-1850 Lagos seems to have had even more proclivity for high-profile deportations, each attended by the resort to the combination of asylum and refuge by the deportee. In 1845, for instance, a supplanting Kosoko supervised the deportation of his predecessor, King Akintoye. As a result, Akintoye became a refugee in Abeokuta and eventually an asylee in Badagry.[22]

While the political ascendancy of British agents in Lagos, Badagry, Abeokuta, Benin, Calabar, Bonny, and their outlying areas was intensified between 1845 and 1850, little evidence exists to support major change attributable to the British regarding conventions integral to deportation-catalyzed asylum among Nigerian polities at the time. However, some novelties began to enter the trajectory of deportation in the area from 1851. First, Kosoko was himself deported and consequently forced into asylum in Epe in 1851 by the ascendent British overlords of Lagos. [23]

After the deportation of Kosoko, other significant changes then followed in the Nigerian are, including the onset of deportation documentation, new terms of deportation suggestive of partnership between Nigerian ethnicities and British agents, the foreseeable deportation of Nigerian autochthons out of Africa, and the insertion of Nigerian deportation practices into English common law. These changes were foreshadowed by the treaties that Great Britain signed with Lagos on January 1, 1852, and with Abeokuta later that year; given that in article 5 of both treaties, “Europeans or other persons now engaged in the Slave Trade, are to be expelled the country.” [24]

From then on, the deportation conventions, principles, and practices that had existed among the ethnicities and polities of the Nigerian area up until 1852 entered a previously unknown phase, including deportation warrants, deportation orders, codified deportation laws, and new deportee profiles all the way down to deportee- King Asani of Addo in 1899.[25]

Olatunde Taiwo is presently a Lisa Maskell doctoral candidate at the Department of History, University of Ghana. He holds an M.A in African History from the University of Ibadan and is currently also a junior Faculty at the Department of History and Diplomatic Studies, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Nigeria. Olatunde’s primary research area is Deportations involving Nigeria, 1800-2020. Olatunde has been awarded fellowships and grants by the Gerda Henkel Siftung; Havard University; G.R. Ford Presidential Foundation; the Robert J. Dole Institute of Politics, University of Kansas; and the British Academy through Professor Richard Cleminson. His article-Knights of A Global Countryside -features in the Historical Perspectives on Economics, Politics and Health in Nigeria, Milwauke:Goldline and Jacobs Publishing (2020), edited by Chima Korieh and Chiamaka Ihuoma.

Title Image: Calvacade in the capital of the Benin Empire (Nigerian area)in the seventeenth century. From Description del’ Afrique, Olphert Dapper. See Hodgkin Thomas, Nigerian Perspectives. An Historical Anthology. (London: Oxford University Press, 1960), 160b.

Further Reading:

Adekunle, Adedeji and Bolaji Owasanoye eds. Internal Deportation of Nigerians Within Nigeria: Legal Policy and Political Appraisal. Abuja: Nigerian Institute of Advanced Legal Studies,2015.

Aldrich, Richard, Banished Potentates: Dethroning and Exiling Indigenous Monarchs under British and French Colonial Rule, 1815–1955. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018.

Asiwaju, Anthony I. “The concept of frontier in the setting of states in pre-colonial Africa.” Presence Africaine 3 (1983): 43-49.

Falola, Toyin, and Matthew Heaton, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Nigerian History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022.

Langer, Christain, Egyptian Deportation of the Late Bronze Age: A Study in Political Economy. (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2021.

Powell, Michael. “The clanking of medieval chains: Extra-judicial banishment in the British Empire.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History Vol. 44, No. 2 (2016): 352-371.

Endnotes:

[1] The period between 1800 and 1852 falls into the precolonial period of Nigerian history. In this period, the Nigerian area was defined by many large centralised states and hundreds of decentralized states. These states were essentially constituted by kingdoms, empires, chiefdoms, city-states, caliphate, villages, and village-groups. All of these were however dissolved and reorganized into the protectorates, colony, divisions, and districts that defined effective British colonial rule between 1898 and 1960.

[2] W. J. Douglas, Annual Report for the District of Ikorodu 1899, 11-51. British National Archives Electronic Database (hereafter cited as BNAD), microform.digital/boa/documents/7917/political-reports-by-district-1899-1911; Cummin, H.W. Badagry. Report on the Western District 1900, 38-47. BNAD. 2; Payne John, Payne’s Lagos and West African Almanack and Diary For 1882, (London: BW.J. Johnson), 56-57; Falola Toyin, “Political Revolutions in Nineteenth-Century Nigeria,” Falola, Toyin and Matthew Heaton, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Nigerian History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022),

[3] Jacob Ade Ajayi, Christian Missions in Nigeria 1841-1891: The Making of a New Elite (London: Longmans, Green and Co Ltd), 3.

[4] Anna Martin Hinderer, Seventeen Years in the Yoruba Country 1827-1870, (London: The Religious Tract Society, 1877); Fadipe, Nathaniel, The sociology of the Yoruba, (Ibadan: Ibadan University Press, 1970), 249

[5] C Hornby-Porter, Report for 1899 That Portion of the Lagos Hinterland Under The Control of Ibadan, 112-113. BNAD 2.

[6] National Archives Ibadan, Nigeria, (NAI hereafter). Olubadan Okunola to The District Officer, Ibadan, 24th August, 1939, Oyo Prof 2/1, Ordinance to Regulate the Deportation of Undesirable Persons

[7] Olumide Lucas, The Religion of The Yorubas (Lagos: C.M.S. Bookshop, 1948), 120-127

[8] F. C. Fuller, Ibadan. Report for the Year 1900, 10-27. BNAD 2; Johnson, Samuel, The History of the Yorubas. From Earliest Times to the Beginning of the British Protectorate. (Lagos: C.M.S. Bookshops, 1921), 4-34; Hodkin Thomas, Nigerian Perspectives. An Historical Anthology. (London: Oxford University Press, 1941), 87

[9] Ellis A.B. The Yoruba-Speaking Peoples of the Slave Coast of West Africa, (London: Chapman & Hall, 1894) , 15-16; Perham Margery, Native Administration in Nigeria (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1937), 11; Biobaku Saburi, Egba and Their Neighbours, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1957), 33

[10] Ames C.G. Gazetteer of Plateau Province, 1933, 24

[11] Ajisafe Moore. The Laws and Customs of the Yoruba People. (London: George Routledge and Sons, Ltd, 1924), 27-35

[12] Ajisafe Moore. The Laws and Customs of the Yoruba People, 24-25

[13] Johnson, Samuel, The History of the Yorubas, 102

[14] Murray Last. The Sokoto Caliphate, (London: Longmans, Green and Co Ltd, 1967), 131

[15] Palmer H.R. Borno Gazetteer, 1929, 20-21

[16] Robin Law, “The Career of Adele at Lagos and Badagry, c. 1807-c. 1837.” Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria 9, no. 2 (1978): 41-43; Cole Patrick. Modern and Traditional Elites in the Politics of Lagos (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 975), 23.

[17] Obara Ikime, The Fall of Nigeria.The British Conquest. (London: Heinemann Educational Books Ltd, 1977), 45

[18]E. G. Dupigny, Gazetteer of Nupe Province, (London: Waterlow & Sons Limited, 1920), 10-11; Elphinstone, K.V. Gazetteer of Ilorin Province(London: Waterlow & Sons Limited, 1920), 35-36; Nadel, Frederick. A Black Byzantium. The Kingdom of Nupe in Nigeria (London: Oxford University Press, 1942),78; Adeleye, Richard. Power and Diplomacy in Northern Nigeria. The Sokoto Caliphate and its Enemies (London: Longman Group Limited, 1977)

[19] Dupigny E.G. Gazetteer, 10-11; Elphinstone, K.V. Gazetteer, 35-36; Nadel, Frederick. A Black Byzantium, 80;

[20] Ames C.G. Gazetteer of Plateau Province, 257

[21] Samuel Johnson, The History of the Yorubas, 289-291

[22] A. B. Ellis, The Yoruba-Speaking Peoples of the Coast of West Africa (London: Chapman and Hall, LD, 1894), 14-15; Babatune Agiri, Architecture as a Source of History: The Lagos Example. In A. Adefuye et al. eds. History of the Peoples of Lagos State, 330

[23] Jide Osuntokun, Introduction of Christianity and Islam in Lagos State In A. Adefuye et al. eds. History of the Peoples of Lagos State,128; Geary, William. Nigeria Under British Rule. (London: Frank Cass and Co Ltd, 1927), 34

[24] John Payne, Payne’s Lagos and West African Almanack and Diary For 1882, 113-14; Losi Ogunjimi. J. History of Abeokuta (Abeokuta: Bosere Press, 1924), 154-157

[25] NAI. CSO 1/1. 27. Government House Lagos to Secretary of State for the Colonies,9 August 1899; Ross R.J.B. Badagry. Western District, 34-35. BNAD 2.