By Giuseppe Perelli

During the Restoration period following Napoleon’s fall in the nineteenth century, international secret societies emerged. These societies generally promoted dissent from absolutist forms of power and served as a unifying force for liberals, constitutional-monarchists, and republicans. They shared ideologies, and iconographies. Their clandestine quality gave them strength and helped them to evade surveillance, but it also allowed their enemies to craft propaganda picturing them as deceitful and destructive. The story of the fictitious lodge of Carbonari in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, the secret society born during the French government in Naples (1806-1815), stands a paradigmatic example of this conservative propaganda[1]. The two organizers used political language and symbols typical of the Carbonari’s culture for extortion purposes.

In 1824, the Bourbon police began investigating complaints about an alleged lodge of Carbonari who were taking shelter in a monastery in Nola. The initial focus of the investigation centered on Biase Peluso, regarded as a bandit who, after attacking travelers, sought refuge in the nearby Apennine mountains. Soon, more details emerged about his connections with those residing in the monastery. The accounts and records indicate that he shared the spoils of his robberies with the Carbonari in return for shelter and protection.

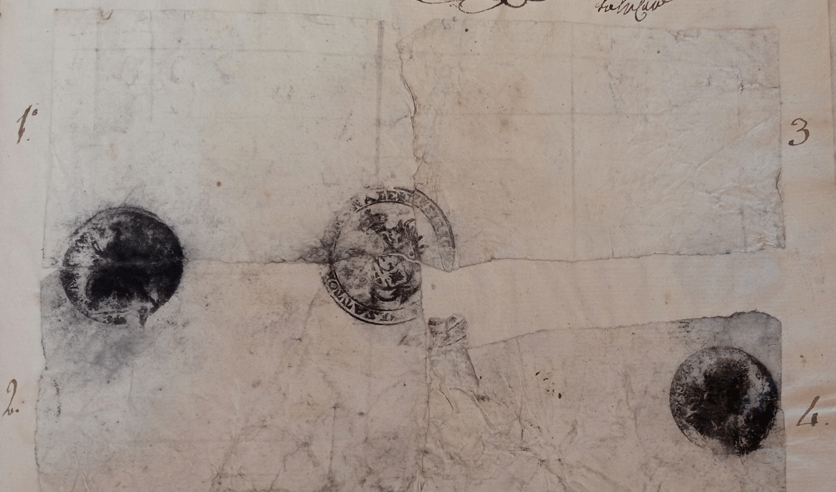

Early clues pointed to suspicion surrounding the subdeacon Francesco de Lucia, believed to have originated the Carbonari faction. Confirmation of his involvement surfaced with the discovery in his personal monastic cell of a sheet of paper inscribed with characters in yellow. The sheet bore the words: “Naples, District of Nola; no one may molest the B[uon] C[ugino] who possesses it, paid carlins six.” (Carlins referred to the silver coins in the Neapolitan monetary system) On the reverse side, the text read: “The present I must show in case of need to the people of our pertinence, and not to others.” ‘Buon Cugino,’ translating to ‘Good Cousin,’ served as the code name for the Carbonarians. Several key witnesses in the investigation acknowledged obtaining documents like this from the subdeacon. The document further indicated that the Intendant, representing the government of Naples in the province, observed three ink seals attached to it. However, only one was identifiable: the official stamp of the municipality of Sirignano, which de Lucia had acquired from his father, a former tax collector.

A torn certificate, reassembled by police. Image courtesy of the author.

Later, officers continued to search de Lucia’s personal cell in the convent, and during the second search, they discovered an unspecified British coin. The officers in charge believed it might be the matrix for the two seals on the torn papers that were only partially legible. The police commissioner provided more specific information about the coin, noting that one side depicted “King George,” while the other featured “a woman representing Britannia.”

What became clear was that the two partners, the subdeacon de Lucia and the bandit Peluso, would meet at the monastery to advance their goals. The subdeacon focused primarily on forging certificates, using the municipality’s stamp and the British coin, as well as a yellow-colored powder he used to draw votive images. According to his testimony, he was inspired by the practice during the constitutional regime of 1820-21 when those who joined the Carbonari sect received a certificate called a “patente,” for which a sum of money had to be disbursed. Motivated by this, he decided to invent “certificates” that would serve as an “attestation of ascription,” offering them in exchange for money. Meanwhile, Peluso was in charge of persuading individuals to pay for these certificates, even resorting to threatening methods, as he was accustomed to doing.

However, the apparent superficiality observed in this matter does not address the questions surrounding the certificate and its associated seals. The subdeacon did not clarify why he specifically chose that exactly coin. The decision to use a female allegory representing Britannia was likely an attempt to emulate Carbonari seals, where such female allegories were frequently featured. The coin in question was a 1774 copper halfpenny that de Lucia received from a novice of the convent, along with other ancient coins.

Revere, Paul, Design for the obelisk celebrating the repeal of the Stamp Act, 1766. Etching, 9 3/8 x 13 1/8. Source: Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/2003690787/).

The use of Britannia in political communication to symbolize political liberty out of its original background was forged in an Atlantic circulation context beginning in the second half of the 18th century. She was often in association with the “liberty cap”, following the classical model of female figures called upon to represent political virtues, revived by the scholarly tradition in the seventeenth century. Paul Revere, the American engraver and patriot, is credited with the first introduction of the “liberty cap” (modeled after the Roman pileus traditionally associated with the practice of freeing slaves) in the allegorical representation of the rebellion of the colonies in a plan for the construction of a memorial obelisk erected in Boston in 1766 in honor of the rebellion against the Stamp Act (1765). The cap appeared twice, both on the tip of a pole held by one by female figures representing the Goddess of Liberty.[2]

Images courtesy of the author.

Four years later, Revere himself designed the frontispiece that began featuring in the “Boston Gazette” from the first issue in January 1770. In this case, the female figure associated with the “liberty cap” was explicitly Britannia in her classic pose seated on a British shield (1606 version of the union jack) dating back to the seventeenth century, became more established in the first half of the eighteenth century through illustrations, medals, and coin. It was ultimately immortalized in an engraving by Francesco Bartolozzi, based on a design by Giovanni Battista Cipriani—a Florentine and one of the founders of the Royal Academy of Arts. Paul Revere’s combination of the Goddess of Liberty with Britannia might seem contradictory for a patriot supporting the colonies’ rebellion. However, it underscores how images and text were pliable for various political messages. Such a combination between 1780-90 was undermined in the fledgling United States of America by an original and youthful “Libertas Americana” in part due to the contribution of French artist Augustin Dupré, a collaborator of Benjamin Franklin who, with a commemorative medal of the Declaration of Independence forged in 1783, influenced the following coin production. In U.S. illustrations, this shift was symbolically represented by the transition of the cap from Britannia’s hands to America’s, marking a kind of symbolic dethroning[3].

A canonical example of a Carbonari seal with female allegory and her attributes. Image courtesy of the author.

Thanks in part to the iconographic transformations of the female allegory in revolutionary France, which led to its consecration as a symbol of liberty, its dissemination became possible even in the Italian peninsula from 1796 onward through coins, municipal seals, and engravings. Familiarization with the symbolic practices associated with the allegory of “Liberty” was such that it triggered appropriations. A noteworthy source for examining the reuse of the figurative elements of “Liberty” is found in the Carbonari seals. These seals serve as an intriguing study, illustrating the allegory’s success in its politicized form, even during the Restoration years. The Atlantic revolutions moved through Italian clandestine networks.

Giuseppe Perelli is a doctoral candidate at the Scuola Normale Superiore of Pisa. His main field of research concerns secret societies in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, with particular interest in both cultural aspects, criminalization of political dissent and the repressive policies of the Bourbon regime.

Title Image: “America Triumphant and Britannia in Distress.” Source: Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003690789/

Further Reading:

Banti, Alberto Mario. Bizzocchi, Roberto (eds.). Immagini della nazione nell’Italia del Risorgimento. Roma: Carocci, 2002.

Benigno, Francesco. Scuccimarra, Luca (eds.). Simboli della politica: Roma: Viella, 2010.

Harden, David. “Liberty Caps and Liberty Trees”, Past & Present, 146/1, 1995, pp. 66-102.

Hunt, Lynn. Politics, Culture and Class in the French Revolution. Berkeley-Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2016 (1984).

Korshak, Yvonne. “The Liberty Cap as a Revolutionary Symbol in America and France”, Smithsonian Studies in American Art, 1/2, 1987, pp. 52 – 69.

Schwoerer, Lois G. “Propaganda in the Revolution of 1688-89”, The American Historical Review, 82/4, 1977, pp. 843-874

Endnotes:

[1] State Archives of Naples, Ministry of General Police, Second Numbering, b. 233, New Septuagint Meeting in the Monastery of San Pietro Cesarano, Province of Terra di Lavoro.

[2] Yvonne Korshak, “The Liberty Cap as a Revolutionary Symbol in America and France,” Smithsonian Studies in American Art, 1, no. 2, (1987) 52 – 69.

[3] See the title image America Triumphant and Britain in Distress, 1782, etching; sheet (irregularly trimmed) 18 x 20.5 cm, in Conress Library (https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003690789/)