By Jiří Juhász

Revolutions are often framed as grand narratives of progress, where the victors dismantle oppressive regimes and build new social orders. However, these stories frequently overlook a critical perspective: the experiences of the “losers”—those who resist change or find themselves marginalized in the aftermath of revolutionary upheaval. Charles Tilly’s The Vendée: A Sociological Analysis of the Counter-Revolution of 1793[1] remains a foundational text for understanding this overlooked dynamic. By exploring the Vendée uprising, Tilly offers profound insights into how revolutions create winners and losers, not only through direct conflict but also through the broader transformations of modernization and cultural realignment. His work challenges the conventional view of revolutions as universally liberating, emphasizing the ways in which revolutions can disrupt established social systems and provoke resistance among those who perceive themselves as being left behind.

Building on this, Tilly’s analysis provides a historical-sociological framework for understanding counter-revolutionary movements across time and place. This framework connects social structures, economic conditions, and cultural values to patterns of resistance, making it particularly useful for analyzing other revolutions, such as the Arab Spring and the revolutions of 1989 and their losers. Just as Tilly demonstrates with the Vendée, these cases reveal how revolutions often provoke backlash from groups whose identities and ways of life are threatened by rapid change. By studying Tilly’s work, we not only gain a detailed account of one of the significant counter-revolutions in history but also tools to interpret similar dynamics in vastly different contexts, including more recent uprisings.

A compelling exploration of this topic can be found in Tilly’s original dissertation, The Vendée: A Sociological Analysis of the Counter-Revolution of 1793. In this work, Tilly examines the uprising of groups rejecting the revolutionary changes that began in 1789. From the outset, it was clear that their efforts in western France were doomed to failure. Despite this, the rural population sought to resist the urban revolution. The events in the Vendée do not fit neatly into the narrative of the Great French Revolution, as they challenge the image of a conflict between the oppressed and the oppressors, where “the people” align with the revolution. Instead, it became evident that symbols of the old regime—the monarchy and the Catholic Church—commanded significant support among broad segments of the population. Thus, Tilly’s examination complicates the simple dichotomy of winners versus losers, showing how even groups that were ostensibly on the “losing” side of history saw their actions as a fight for survival in the face of overwhelming change.

Tilly explores why this group considered themselves the losers of the revolution, even when, from the revolution’s perspective, they should have been on the “winning” side. He further investigates the contrasting experiences of the regions of Mauges and Saumurois.[2] Mauges, a poorer and more urbanized region, became the heart of the revolt against the revolution, while Saumurois, a wealthier and more connected region, showed no signs of resistance. Tilly attributes this contrast to the differing social structures and levels of modernization in each region. Mauges, with its agricultural and textile production, was more urbanized and thus more vulnerable to the revolutionary changes, creating tensions between rural and urban populations. In contrast, Saumurois was wealthier, more integrated into broader French society, and had a more lukewarm religious life, which made it less likely to be swept up by the excitement of the revolution. This contrast between Mauges and Saumurois illustrates how the local dynamics and social fabric shaped the nature of resistance, a theme that resonates in subsequent revolutions. [3]

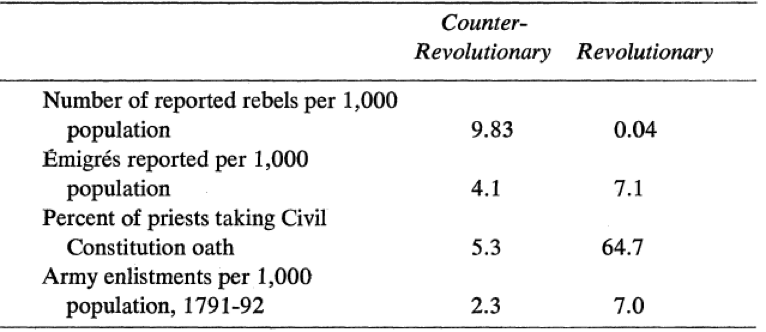

Drawing on these findings, Tilly interprets the rebellion in the Vendée as a response to modernization processes that restructured an agrarian society, which was isolated and characterized by a conservative value system. He adeptly identifies the specific group of losers of the revolution and, more importantly, elucidates the reasons why these individuals felt threatened and defeated by it. Tilly also demonstrates how those opposing the revolution, or later deemed losers, engaged with the new post-revolutionary reality. For example, he presents an illustrative table[4] comparing one of the most anti-revolutionary districts (Cholet) with one of the most revolutionary (Saumur). The counter-revolutionary region exhibited much more resistance to the new reality, which Tilly illustrates through selected factors. In fact, the comparison between these regions further underscores the complex relationship between social transformation and resistance, providing a deeper understanding of how the old order clashed with the new.

Table n.1

He notes that regions resisting revolutionary change had divergent demands and perspectives. On nearly every significant issue, the anti-revolutionary regions sought less change than their revolutionary counterparts. Those opposed to the revolution desired greater continuity in legal, financial, and religious matters. These differences in outlook and demand were not only apparent from 1789 onward but also steadily intensified, highlighting the persistent tensions between modernization and the groups seeking to preserve tradition. These enduring differences echo in later revolutions, including the Arab Spring and the revolutions of 1989, where the “losers” continued to resist change even when it became clear that the old order was no longer viable.

This dynamic of resistance is evident in the Arab Spring, where much like the Vendée rebels, the losers sought to preserve the ancien régime. However, for the Arab counter-revolutionaries, the notion of the ancien régime was not just a pre-modern, pre-capitalist agrarian system but a more recent post-colonial order. As Jamie Allinson[5] argues, while the Arab Spring is often viewed as a failure for the revolutionaries, it can be more accurately interpreted as a success for the counter-revolutionaries who defended the state and the progress they perceived in its achievements. In both the Vendée and the Arab Spring, counter-revolutionary forces were driven by existing classes or closely related social groups, and in both instances, the state emerged as the key actor defending the old order.

While the opponents of revolutionary change in 18th and 19th-century Europe, such as in the Vendée, drew support from the pre-modern, pre-capitalist agrarian past, the context for the rejection of the Arab Spring was markedly different. The Arab republics (with Bahrain being a unique case) had experienced revolutions from above that dismantled their old agrarian structures long before the Arab Spring—during the 1950s and 1960s. Thus, the counter-revolutionary forces sought to draw on the legacy of national development from the post-colonial era as a source of support. [6] For those rejecting the revolutions of the Arab Spring, their defense was centered on the sovereign state, which had been hard-won in the mid-20th century, both materially and symbolically. This encompassed state capitalism, independence from colonial powers, struggles against Israel, and a response to secularism perceived as a characteristic of the regime rather than an absence of faith in public life.

The counter-revolutions of the Arab Spring were not inherently anti-modern or anti-progress. Instead, they represented a defense of a specific form of modernity, one that was centered on the state and its achievements in the post-colonial era, including state capitalism, independence from colonial powers, and resistance to Israel. The counter-revolutionaries claimed their approach to modernity as the legitimate one, defending what they saw as the gains of earlier revolutions from above. This nuanced defense of a particular type of modernity mirrors the complexities of counter-revolutions throughout history, from the Vendée to the Arab Spring.

Similarly, the dynamics of defeat[7] in the revolutions of 1989 in Central and Eastern Europe also mirror the patterns observed in the Vendée and the Arab Spring. While the revolutions of 1989 led to democratization in many countries, they also left behind groups that, although unable to restore the old regime, continued to maintain certain elements of the pre-revolutionary order in their behavior, thinking, and expectations. [8] This situation is similar to the defeated groups in the Vendée and the Arab Spring, who clung to elements of the old system even as the new reality unfolded. As Piotr Sztompka has noted,[9], this clash between internalized patterns and the new system often prevents groups from fully adapting to the new order, leaving them in a state of ongoing tension. These enduring tensions highlight the long-lasting effects of revolution and the complex processes of adaptation and resistance that accompany it.

Piotr Sztompka’s emphasis on the effects of systemic transformation aligns closely with Tilly’s focus on the persistence of pre-existing networks and patterns of behavior. In both the Vendée and post-1989 Central and Eastern Europe, the defeated groups exhibited a strong attachment to old norms and institutions, creating tensions in adapting to the new revolutionary order as we said before.

Just as the Vendéans leveraged shared community and religious networks to sustain their counter-revolutionary struggle, the defeated side of 1989 relied on informal institutional ties and organizational remnants of the communist system. Observation that these internalized patterns often persist even after structural change helps explain why some authoritarian practices, patronage systems, and state-oriented mentalities survived in post-1989 societies. These remnants created ongoing tensions between the ideals of the new order and the lived realities of transition, leaving certain groups in a state of cultural dissonance.

Moreover, Tilly would point to the broader political context in shaping the outcomes of these defeated groups. In the Vendée, the decline of revolutionary terror and instability in the revolutionary government allowed for the persistence of certain elements of the old order. In 1989, the collapse of Soviet hegemony and the rapid push for democratization under Western influence similarly created opportunities for the losing side to adapt. However, this adaptation often involved reinterpreting or repurposing old patterns rather than fully embracing the new system. This resulted in a hybrid post-revolutionary landscape, where elements of the past continued to influence the trajectory.

Tilly would highlight how revolutions often fail to fully eradicate the structures and behaviours of the old regime. Instead, the trauma of rapid transformation leaves behind lingering tensions and unresolved legacies. This dynamic is as evident in the cultural and social legacy of the Vendée as it is in the enduring practices in post-1989 Eastern Europe. So Tilly’s work can also provide a nuanced framework for understanding how revolutions create not only profound change but also deep and lasting continuity.

When we apply Tilly’s framework to the Arab Spring, several themes can also emerge. For example Tilly would argue that Arab Spring counter-revolutionary movements represented a defense of traditional or pre-existing social orders—specifically, state sovereignty, authoritarian political structures, and religious values. Just as the counter-revolutionaries in the Vendée fought to preserve the monarchy and the church, counter-revolutionaries in the Arab world fought to preserve the power of authoritarian regimes, often invoking national sovereignty, security, and religious legitimacy as justifications. Tilly would note how both sets of counter-revolutionaries mobilized support by appealing to social identities and values that were threatened by the revolutionary changes, whether it was secularism, democratization, or economic modernization.

Tilly would point to how these counter-revolutions were enabled by the coercive capabilities of the state—including the military, police, and intelligence services—which were deeply embedded within the social fabric of the regime. Just as the French revolutionary government used brutal force to suppress the Vendée rebellion, Arab regimes used violence, repression, and surveillance to maintain control and stifle revolutionary movements. In this way, Tilly’s analysis provides a crucial lens for understanding the role of state power in counter-revolutionary efforts across different historical and geographical contexts.

Tilly would analyze the role of international dynamics—such as Gulf monarchies supporting counter-revolutionary forces or Western hesitancy toward prolonged democratization—in shaping these outcomes, just as foreign alliances and international pressures shaped the course of events in the Vendée.

In examining the experiences of the “losers” in revolutionary change, Tilly’s work provides a critical lens for understanding the dynamics of resistance and counter-revolution. Whether in the context of the Vendée, the Arab Spring, or the 1989 revolutions, the losers often sought to preserve aspects of the old order. These movements of resistance, while differing in context, are linked by broader social, cultural, and political shifts that revolutions bring about—and by the intense backlash they provoke from those who feel threatened or displaced by these changes.

Jiří Juhász is a Ph.D. candidate at Charles University in Prague, affiliated with the Department of Historical Sociology. He currently teaches theories and histories of revolutions and theories of conflict. His research centers on the Velvet Revolution of 1989 in Czechoslovakia and the group of losers stemming from this revolution. Additionally, he engages with contemporary Czech history and theories of revolution.

Title Image: The Battle of Le Mans (Defeat of Rebels), by Jean Sorieul. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Endnotes:

[1] Tilly, C. (1964). The Vendée: A Sociological Analysis of the Counter-Revolution of 1793. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

[2] Tilly, C. (1964). Tilly, C. (1964). Chapter 3. In The Vendée. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

[3] The aspect of urbanization, as a complicated and weaker point, is pointed out for example by Sewell, W. H., Jr. (1984). Charles Tilly’s Vendée as a model for social history. French Historical Studies, 13(2), 249-264.

[4] Tilly, C. (1963). The Analysis of a Counter-Revolution. History and Theory, 3(1), 30-58, p. 53.

[5] Allinson, J. (2022). The Age of Counter-revolution: States and Revolutions in the Middle East. Cambridge University Press.

[6] ibid., pp. 46-56.

[7] The question of the possibility of revolutions in democracies is (logically) underrepresented, an exception being Gunitsky, S. (2018) ‘Democratic waves in historical perspective’, Perspectives on Politics, 16(3), pp. 634-651. doi: 10.1017/S1537592718001044. or Berman, Chantal, Killian Clarke, and Rima Majed. 2023. WIDER Working Paper No. wp-2023-51. UNU-WIDER.

[8] There is a large literature on the continuity of thought, behavior, and expectations as a remnant of life in the removed regime. For example, Alexievich, S. (2016): The last of the Soviets (B. Schmidt, Trans.). Random House.

[9] Sztompka, P. (2004). The Trauma of Social Change: A Case of Post-communist Societies. In J. C. Alexander, R. Eyerman, B. Giesen, N. J. Smelser, & P. Sztompka (Eds.), Cultural trauma and collective identity (pp. 155-195). University of California Press.

Further Reading:

Ghodsee, K., & Orenstein, M. (2021). Taking Stock of Shock: Social Consequences of the 1989 Revolutions. New York: Oxford University Press.

C. Alexander, R. Eyerman, B. Giesen, N. J. Smelser, & P. Sztompka (Eds.)(2004), Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity (pp. 155-195). University of California Press.

Tilly, C. (1964). The Vendée: A Sociological Analysis of the Counter-Revolution of 1793. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Krapfl, J. (2014). Revolution with a Human Face: Politics, Culture, and Community in Czechoslovakia, 1989-1992. Cambridge University Press.

Ghodsee, K. (2017). Red Hangover: Legacies of Twentieth-Century Communism. Duke University Press.