By Zack White

In a well-received analysis of the British Army in the West Indies, Roger Norman Buckley described that the force’s military justice system as “capricious and arbitrary.”[1] Buckley’s analysis echoed the 18th century commentator on law William Blackstone, who dismissed military law as “arbitrary in its decisions.”[2] More recent scholarship has recognized that although the stipulations of military law’s foundational texts were harsh, the application of this system was much more nuanced.[3] However, whilst the discretionary aspect of the military justice system has increasingly been acknowledged, one facet remains neglected: the extent to which the administration of military law inherently prevented it from being ‘arbitrary’. Examining three revealing case studies drawn from transcripts of military trials, this article uses a legalistic lens to reassess the claim that military justice was ‘capricious and arbitrary’. Far from being “arbitrary,” military law’s application through the courts martial emerges as a carefully considered system, which prioritized the hearing of evidence and enabling witnesses to testify. By adhering to such principles wherever the army was deployed, the officers judging these trials were self-policing, providing a check on their power at a local level, which was also conducted by the government’s administrator of military law in London, the Judge Advocate General. These processes show similarities with those identified by historians of the non-military legal system in Britain during the age of revolution, where courts were bound by the law that they sought to administer.[4] More broadly, this piece encourages readers to examine the complex dichotomy in which legal systems can simultaneously be forms of control and, via their checks and balances, protections against oppression.

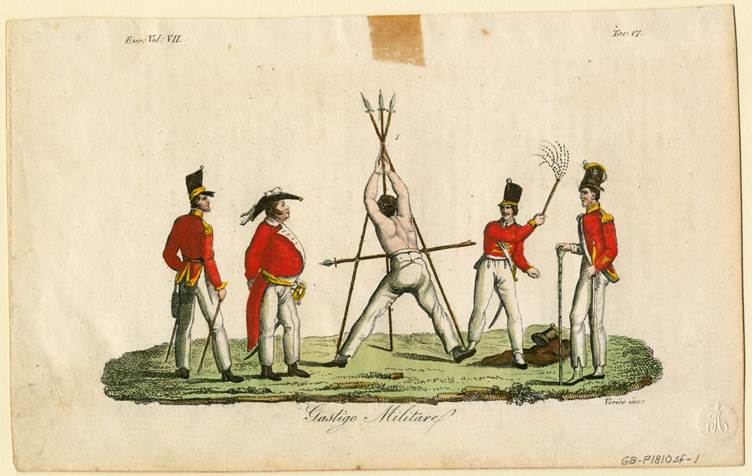

“Gastigo militare” (1810). Prints, Drawings and Watercolors from the Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection. Brown Digital Repository. Brown University Library. https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:228587/

In July 1817, Privates John Minshaw and Samuel Walker of the 103rd Regiment, faced trial in Quebec for desertion. The transcript for their trial highlights that military courts were both sensitive to practices in civilian courts, whilst also embracing practices which best served the army’s needs. Rather than being the final drafts of the proceedings, these proceedings are rougher drafts, containing sections which have been crossed out as the document has been redrafted. As a result, we gain an insight into how the legal process was molded over the course of the trial. Minshaw and Walker both pleaded “guilty.” Curiously though, the trial proceedings state: “The court recommended both the Prisoners, that if they had any favorable circumstances to bring forward in extenuation of their crime, or anyone to bring forward in support of their former good character, to stand their trial in order to have an opportunity to bring forward those evidences, and they both still persisted in pleading guilty to the charge against them.”[5] These events echo the findings of John Beattie, who has demonstrated that guilty pleas were discouraged by judges in non-military courts, as it ensured that all the evidence had to be heard. If the defendant pleaded guilty, the court would immediately proceed with sentencing and could not take any contextual information or extenuating circumstances into account.

The frank statement of motives points to a nuanced application of military law. What makes this case more curious, though, is that the court then proceeded to sentencing, awarding 800 lashes and branding with a letter D (for deserter). However, a legal question was then raised by an unspecified individual as to whether it was legal to proceed with sentencing without hearing evidence, even in the case of a guilty plea. This lack of awareness indicates that a plea of “Not Guilty” was presumed as a matter of course in court martial cases, obligating members of the court to consider the case according to the evidence presented, rather than the whims of the court’s officers. The court therefore adjourned to consult works of legal authority. The next day, it was determined that it was: “invariably practice in the civil courts to consider the voluntary confession of the prisoner in court as countervailing the necessity of further proof, but as the members of the court had never personally witnessed such a course of proceeding they thought it advisable to hear the evidence.”[vi] For Minshaw and Walker, this made no practical difference, as the eventual sentence was the same. There are two interpretations of this. On the one hand, this might reinforce the “arbitrary” argument by questioning the extent to which courts were truly influenced by evidence. However, these men had confessed to their guilt, and their punishment of 800 lashes was by no means the harshest issued for this crime. This example, therefore, highlights that adherence to legal process weighed heavily on the minds of those officiating in military courts.

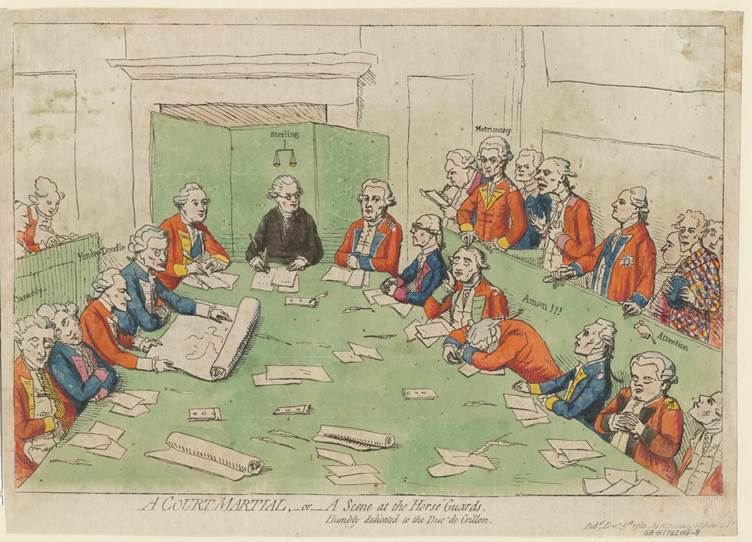

Gillray, James, “A court martial,–or–a scene at the Horse Guards: Humbly dedicated to the Duc de Crillon” (1782). Prints, Drawings and Watercolors from the Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection. Brown Digital Repository. Brown University Library. https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:234193/

When constructing a defense, the ability to articulate effectively was vital. Whilst officers could, and did, conduct lengthy defenses and cross-examinations of witnesses, rank and file cases are often notable for their brevity. In part, this is because the rank and file tended to be accused of crimes which were simpler to prove. Assessing whether a private had deserted was easier than ascertaining if an officer had acted dishonorably, as the latter was subjective. At times, efforts by the rank and file to engage in cross-examination could be awkward and counterproductive. In July 1813, Private Rufus Moon faced trial for desertion, and asked the witness, a civilian who arrested him, whether it was the case that when the witness had found Moon, the private offered to be the civilian’s prisoner. Moon’s attempted defense centered around the notion that he had willingly surrendered himself to the witness when he was apprehended. If force had not been required to bring him back to the unit, this could undermine any claim that he had actively sought to stay away from his unit. However, the awkwardly framed question resulted in a devastatingly emphatic response from the witness: “No, but […] he offered me five dollars to let him escape”. Unsurprisingly, Moon was found guilty of desertion and executed.[7] Clearly, his strategy had been hindered by an inability to articulate himself, which can be attributed to a lack of both education and experience in legal process. Nonetheless, the fact that he attempted to inject ambiguity into judges’ assessment of his actions speaks to a knowledge amongst the rank and file of how to ameliorate certain charges. Whilst he could not deny that he had been absent from his unit, Moon knew that if he could imply that he had been willing to return, he might secure a more lenient punishment. He therefore sought to manipulate the legal process, rather than passively accept whatever punishment the court decided upon. The sheer existence of a facility for defendants to cross-examine witnesses inherently undermines the notion that justice was disseminated “capricious” justice.

Whilst this inexperience in constructing a defense could therefore place the rank and file at a disadvantage when seeking to undermine a charge, all trials were nonetheless evidence-led, and all witnesses had to be heard. One notable example of the courts’ patience in awaiting a witness arose during Private John Williams’s trial for desertion. Williams claimed to the court that “he is not always in his perfect senses, therefore at times does not know what he does”. After hearing evidence from two witnesses that contradicted this claim, Williams called an entirely new witness who he insisted would be able to testify on his mental state. The court therefore adjourned until this new witness could be located and brought before the judges. Unfortunately for Williams, the man testified that he knew nothing about him whatsoever. Williams was found guilty and sentenced to serve for life.[8]

These brief case studies emphatically counter the idea that the military justice system was arbitrary in its practices. This is not to imply that the system was without flaws, but this article reminds scholars of the need to carefully appraise the divide between the letter of the law and the realities of its implementation.

Zack White is an award-winning historian and Leverhulme Early Career Research Fellow based at the University of Portsmouth with a particular interest in military law, soldier experiences, and race in the armed forces at the turn of the nineteenth century. The host of the Napoleonic Wars Podcast and Youtube channel, and founder of the Napoleonic and Revolutionary War Graves Charity, he is also the coordinator of the Heritage 1815 initiative. He has released two edited collections: The Sword & the Spirit: Proceedings of the First War and Peace in the Age of Napoleon Conference, and An Unavoidable Evil: Siege Warfare in the Age of Napoleon. His latest research looks at the role of racialized attitudes in the legal experiences of sepoys and lascars in the East India Company’s Army and Navy.

Title Image: “All Hands to a Court Martial.” Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Further Reading:

Alryyes, Ala. “War at a Distance: Court-Martial Narratives in the Eighteenth Century.” Eighteenth-Century Studies. Vol. 41, 4 (2008): 525-542.

Beattie, John, Crime and the Courts in England 1660-1800. Clarendon Press, 1986.

Berkovich, Ilya. Motivation in War: The Experience of Common Soldiers in Old-Regime Europe. Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Buckley, Roger N. The British Army in the West Indies: Society and the Military in the Revolutionary Age. University Press of Florida, 1998.

Conway, Stephen. “‘The Great Mischief Complain’d of’: Reflections on the Misconduct of British soldiers in the Revolutionary War.” The William and Mary Quarterly. Vol. 47, 3 (1990): 370-390.

Coss, Edward J. All for the King’s Shilling: The British Soldier Under Wellington, 1808-1814. Oklahoma University Press, 2010.

Cozens, Joseph. “‘The Blackest Perjury’: Desertion, Military Justice, and Popular Politics in England, 1803–1805.” Labour History Review. Vol, 79, 3 (2014): 255-280.

King, Peter, Crime and Law in England, 1750-1840. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Lockley, Tim, Military Medicine and the Making of Race. Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Steppler, Geroge. “British Military Law, Discipline, and the Conduct of Regimental Courts Martial in the Later Eighteenth Century.” English Historical Review. Vol. 102, 405 (1987): 859-886.

Endnotes:

[1] Roger Buckley, The British Army in the West Indies Society and the Military in the Revolutionary Age (University Press of Florida, 1998), 244.

[2] William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England (Clarendon Press, 1765), p. 400.

[3] Zack White, “Pragmatism & Discretion: Discipline in the British Army, 1808-1818,” (Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Southampton, 2022); Kevin Linch, The British Army: 1783-1815 (Pen and Sword, 2024), p.110.

[4] John Beattie, Crime and the Courts in England 1660-1800 (Clarendon Press, 1986); Peter King, Crime, Justice and Discretion in England 1740-1820 (Oxford University Press, 2000).

[5] Southampton City Archives, D/PM 20/34. Trial of Privates John Minshaw and Samuel Walker, 24 July 1817. This quote was crossed out in the drafting process.

[6] Southampton City Archives, D/PM 20/34. Trial of Privates John Minshaw and Samuel Walker, 24 July 1817.

[7] Southampton City Archives, Page and Moody papers, D/PM 20/26, Trial of Private Rufus Moon, 21 July 1813.

[8] The UK National Archives, War Office 71/214 General Court Martial Proceedings, Trial of Private John Williams, 29 August 1808.