By Oriane Guiziou-Lamour

For the last few years, France has seen a growing interest in rediscovering women authors from the modern period, whose works were either lost or purposefully erased from literary history, an erasure that especially affected erotic fiction written by women. While scholarship in the 1990s and early 2000s across the Atlantic by Joan Hinde,[1] Lucienne Frappier-Mazur,[2] Huguette Krief,[3] and Valérie André[4] on eighteenth-century women authors did not trigger a wave of reissues, this renewed attention now brings their works back into circulation. For instance, in 2024, Romain Enriquez and Camille Koskas edited the anthology Écrits érotiques de femmes, Une nouvelle anthologie du désir,[5] which finally bridges the gap between scholarship and public-facing research, highlighting an overlooked history of erotic works by women authors. The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries appear particularly rich, as evidenced by the works of Suzanne Giroust de Morency, Félicité de Choiseul-Meuse, and Marie/Elisabeth Guénard de Méré, who all wrote during this period. Often considered in isolation, their little-known works call for a joint study, not merely because they were all published during a similar period (1790–1820), but more importantly because they share a tension between writing eros and adhering to morality, as well as a troubled negotiation with the memory of the French Revolution.

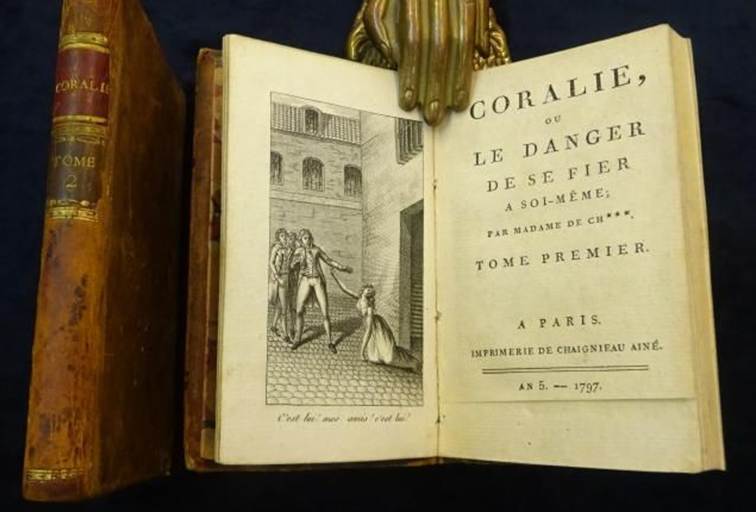

Between 1797 and 1800, that is during the Directory and the early years of the Consulate, each of these authors published a novel drawing on the aura of fantasy that shrouded the prisons of the Terror years (1793–94),[6] blending elements of lived experience, the rise of an anti-revolutionary literary tradition, and the influence of the Gothic novel. Coralie, ou le danger de se fier à soi-même (1797) by Félicité de Choiseul-Meuse, a highly rare novel today,[7] recounts the sentimental journey of the young Coralie and her lover Dolinsac, who are both imprisoned during the years of the Terror. Irma, ou les malheurs d’une jeune orpheline (1799), by Marie/Elisabeth Guénard de Méré,[8] is a fiercely anti-revolutionary roman-à-clef set in a fictionalized India, recounting the tragic story of Marie-Thérèse de France, daughter of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette. Illyrine, ou l’écueil de l’inexpérience (1799–1800), by Suzanne Giroust de Morency, follows the sentimental journey of Suzanne, an unhappily married woman who leaves her husband and daughter to reunite with her first lover in Paris, embarking on a series of romantic entanglements. In the third volume, the tide of history ultimately sweeps her up, and authorities imprison her in the prison des Anglaises.

In these works, sexuality serves as the prime locus of scrutiny, offering in turn the opportunity to explore the libertine possibilities of confinement favoring promiscuity (Giroust de Morency), to present revolutionary violence as sexual deviance and vice (Guénard de Méré), or to philosophically interrogate the relevance of a moral code of sexual conduct imposed upon women in a context where death is ever-present (Choiseul-Meuse). In any case, these understudied novels invite a renewed literary interpretation of the Terror and its aftermath in texts written by women authors. Such an interpretation centers on women’s multifaceted experience in the prison space, whether marked by the menacing accretion of sexual violence or by the revolutionary possibility for women to act upon their sexuality.

1793-94: Fictional and Revolutionary Disenchantment

By imprisoning their heroines, the authors place their works within the literary tradition of récits d’emprisonnement, a genre that flourished during the Terror, as Luba Markovskaia has shown in her work, building on Victor Brombert’s insights.[9] It gained popularity, as Cécile Tarjot notes, because “the topic of love in revolutionary prisons consistently generates passion as it orchestrates the conjunction of three powerful imaginaries: sentimental, revolutionary, and carceral”[10].

The imprisonment of Giroust de Morency’s Illyrine and Choiseul-Meuse’s Coralie reflects the “suffocating atmosphere [of 1793-1794], where the obsessive fear of schemes and the Jacobin ideal of transparency cast suspicion on everything secret.”[11] In these fictionalized accounts of the Revolution, love and desire become political transgressions, turning into charges made against characters. Coralie and her lover Dolinsac are imprisoned solely based on a false allegation made by the woman he abandoned, just as a jealous woman accuses Illyrine of being a spy. Illyrine skillfully weaves together humor, sexuality and politics, as the heroine’s prolonged stay in the prison des Anglaises stems from a list of lovers discovered in her home: “Corine went to the door, more dead than living: an entire revolutionary committee accuses me of harboring councils in my house with Séchelles, and thus arrests me in the name of justice, seals my belongings, seizes all of my documents, and writes an official report.”[12] The heroine realizes too late the folly of keeping such a list: “Oh, Lord! It is true indeed, this list contained the names of all my lovers, marked by the first letter of their name and their occupation.”[13] In the context of a widespread hunt for internal enemies, the author satirizes the absurdity of revolutionary committees, while illustrating the peril of having had illustrious lovers, especially when those men are famous revolutionaries.

While Illyrine is initially enthusiastic about the Revolution and Coralie blindly ignorant of the events unfolding, the imprisonment of the female heroes reflects a progressive fictional disillusionment that mirrors the revolutionary disenchantment of their authors. Robespierristes and their supporters are denounced by Giroust de Morency as “crim[inals]” and “cannibals” by Guénard de Méré and Choiseul-Meuse. While each novel presents a distinct perspective on the Revolution, the authors unite in their condemnation of the violence inflicted by citizens upon one another.

Sexual Violence and Sexual Liberation

From this vantage point, women appear particularly vulnerable to revolutionary violence, their bodies reduced to bargaining chips in a brutal political game. In Irma, Ximacelem (Maximilien Robespierre) attempts to persuade the heroine to marry him. When she resolutely refuses, he retaliates by worsening the conditions of her imprisonment: “Never shall the brightness of the skies be replaced by that of lamps! She should be given the coarsest of food, not enough to starve from hunger, and too little to satisfy her hunger. Remove these perfumes, these delectable dishes; she will never find pleasure in them again until the day she consents to becoming the contented wife of Ximacelem!”[14] Choiseul-Meuse places Coralie in a similar predicament. Before being imprisoned herself, she desperately tries to uncover the whereabouts of her lover, seeking his liberation:

Coralie was a beauty, and she was recognized as such by one who, by his status, surely knew the depths of these gloomy prisons. He promised to reveal the name the one in which her lover was held, and to help her save him. She threw herself at his feet, […] her touching gratitude overflowing. But the barbarian, moved by her tears, found in them new incitement for his shameful desires. […] Her refusal only stirred the cruelty of her protector, and Coralie, ignominiously dismissed from his house, once more thanked Providence for sparing her from the even greater affront she might have suffered.[15]

Front piece from Guénard de Méré’ 1799 novel, Irma, ou les Malheurs d’une jeune opheline

Egalitarian aspirations are synonymous with a rise in sexual violence, particularly against young women from respectable families. Unlike Coralie and Irma, Illyrine’s time in prison notably reflects a decrease in sexual violence. In this novel, such violence is more closely associated with female mobility, while imprisonment becomes a space for the liberation of female desire.

In Irma, a chaste and moralistic novel, sexuality is aligned with revolutionary vice. Irma finds it necessary to reassure her husband of her physical (and implicitly sexual) integrity during her imprisonment, affirming that she was never the “plaything of [her jailers’] abhorrent desires.” Guénard de Méré portrays Ximacelem in similarly charged terms, not only as physically grotesque, but also as morally corrupt, in sharp opposition to the moral ideal embodied by Irma. Guénard de Méré and Choiseul-Meuse place their heroines on the frontlines of history, where the threat of sexual violence shadows every stage of their captivity.

Nevertheless, prison can briefly relieve the anxiety of an uncertain future by uniting lovers. For men, it becomes a space where the female body serves as a medium for sublimating the fear of probable death. In Coralie, Dolinsac invokes the certainty of his own demise to persuade Coralie to consummate their union finally: “Overcome by love and the dread of impending death, drawn to pleasure by the very excess of despair, Dolinsac obtained the prize of the most ardent passion.”[16] Morality softens in the face of the impending specter of death. The author presents a masculine reclaiming of anxiety in the revolutionary context, embodied by men eager to possess the women they desire. However, viewing it solely as exploitation overlooks the more nuanced view of sex developed by Choiseul-Meuse, one that allows the heroine to absolve herself of responsibility for intercourse. The narration condemns the couple as mere window-dressing, a moralistic judgment intended to maintain decency for both reader and author. Although Coralie is later held accountable for violating moral codes with her lover, they are ultimately reunited at the end of the novel.

Carceral Communities and Collective Healing

The bonds that unite Irma with her family and companions, Coralie with Dolinsac, and Illyrine with the milord who cares for her, all together point to the central role of community within the prison space: a vital means of alleviating the anguish of the present. Notably, the sublimation of sexuality in Irma does not entail the absence of romantic love; on the contrary, it intensifies its emotional depth. In the fake memoir, desire is sublimated through filial and familial love, reflected in the blood ties uniting Marie-Thérèse de France and her husband, Louis de France, first cousins. The enduring memory of the beloved is enough to stave off the anxieties of the present by nourishing the hope of reunion. While prison signifies future pleasure for Irma, it represents, for Illyrine, the reawakening of pleasure: “We all imagined ourselves so near the end of our career, that we sought to enhance its final moments. If a poor soul were to face the sentence of his death, we would try to make his end as agreeable as possible, each of us striving to outdo the other.”[17]

The narrator depicts a prison that reestablishes a gallant, libertine utopian community in which the pursuit of pleasure becomes a shared aspiration. In a world where time is uncontrollable, prisoners attempt to master space, creating a paradoxical environment of hedonism beneath the guillotine’s shadow. Choiseul-Meuse similarly portrays a community where the certainty of death draws individuals closer and unleashes buried passions: “Coralie, whose window was low, thought she recognized a voice. […] Without hesitation, she rushed into the courtyard, recognized Dolinsac, and collapsed at his feet […]: ‘It’s him! My friends, it’s him!’ Coralie, who had always been so timid, no longer noticed that two dozen people surrounded her. She revealed, without hesitation, all the secrets of her heart. She went further: she called them friends. She was right: those who suffer misfortune are brethren.”[18] A moment of fraternal communion mirrors this recognition scene between Coralie and Dolinsac. Thus, while people tear each other apart outside, the prison becomes a space where the revolutionary ideals of equality and fraternity are, at last, enacted, serving the authors as a means of highlighting what seems to them the great paradox of the Revolution during 1793-1794: preaching fraternity while slaughtering one another.

Conclusion: Prison as (En)closure

When the French Revolution broke out, Giroust de Morency and Choiseul-Meuse were both 22 years old in 1789, while Guénard de Méré was 36 years old. For these authors, writing about love and sexual pleasure in Terror prisons appear not only as means for their heroines to endure the Terror, but more importantly as vehicles for working through the trauma of having lived it[19]. Sexual pleasure and love emerge not only as sources of resilience for the heroines in the face of the Terror, but also as a means through which the authors attempt to reckon and recover from its lasting wounds. While the portrayals of love and sexuality diverge significantly for these authors, underscoring the diversity in representations of the prison space across their novels, all published within just a few years of each other, Guénard de Méré, Giroust de Morency and Choiseul-Meuse are united in their condemnation of the Terror and express clear relief brought about by the Thermidorian Reaction. In these novels, the prison space contrasts with the continual threat and bloodshed of the outside, presenting the interior as an almost utopian haven. This space, while confronting the heroines with the loss of loved ones outside, ensures their physical integrity and offers the possibility to challenge moral norms. The shared need to love, to endure the anxiety of an uncertain future, along with the yearning for community, thus emerges as a means of withdrawing the characters from the violence of the Revolution.

Oriane Guiziou-Lamour is a doctoral candidate (ABD) in the Department of French at the University of Virginia. She studies the relationship between gender, sexuality and power during the eighteenth century. Her dissertation, titled “Le libertinage interdit: le roman érotico-sentimental ou développement et disparition d’un érotisme au féminin” explores the writings of Giroust de Morency, Choiseul-Meuse, and Guénard de Méré, as well as the active efforts of nineteenth-century critics and politicians to erase their work from literary history. Her most recent article, “Suzanne Giroust de Morency ou ‘Illyrine l’évaporée’ : de la confusion (auto)biographique au fantasme littéraire” was published in the journal Dix-huitième siècle.

Title Image: Interior of the La Conciergerie, the main holding area for prisoners during the terror in Paris. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Further Reading:

Note: While the relatively little-known novels mentioned in this article haven’t been translated into English, Dorothy Albertyn translated in 1970 Julie ou j’ai sauvé ma rose (1807), one of Félicité de Choiseul-Meuse’s novels, under the shortened title Julie.

Lucienne Frappier-Mazur, “Marginal Canons: Rewriting the Erotic,” Yale French Studies, no. 75 (1988): 112-128.

Beth Ann Glessner, Libertinism and Gender in Five Late-Enlightenment Novels by Morency, Cottin, and Choiseul-Meuse (Pennsylvania University, 1994).

Huguette Krief, Vivre libre et écrire. Anthologie des romancières de la période révolutionnaire (1789-1800) (Voltaire Foundation, 2005).

Joan Hinde Stewart, Gynographs. French Novels by Women of the Late Eighteenth Century (University of Nebraska Press, 1993).

Endnotes:

[1] Joan Hinde Stewart, Gynographs. French Novels by Women of the Late Eighteenth Century (University of Nebraska Press, 1993).

[2] Lucienne Frappier-Mazur, “Convention et subversion dans le roman érotique féminin (1799-1901),” Romantisme, no 59 (1988): 107-119. For its translation in English, see Lucienne Frappier-Mazur, “Marginal Canons: Rewriting the Erotic,” Yale French Studies, no 75 (1988): 112-128.

[3] Huguette Krief, Vivre libre et écrire. Anthologie des romancières de la période révolutionnaire (1789-1800), (Voltaire Foundation, 2005).

[4] Valérie van Crugten-André, “Félicité de Choiseul-Meuse: du libertinage dans l’ordre bourgeois,” Études sur le XVIIIe siècle. Portraits de femmes (Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles, 2000).

[5] Romain Enriquez, Camille Koskas, Écrits érotiques de femmes. Une nouvelle anthologie du désir. De Marie de France à Virginie Despentes (Bouquins, 2024).

[6] For literary studies on the period, see Huguette Krief, Entre terreur et vertu. Et la fiction se fit politique… (1789-1800) (Honoré Champion, 2010), and Stéphanie Genand, Le Libertinage et l’histoire: politique de la séduction à la fin de l’Ancien Régime (Voltaire Foundation, 2005).

[7] My thanks go to the Department of Early Printed Books and Special Collections at the Library of Trinity College Dublin, which granted me access to consult its unique copy of Coralie. Surprisingly, the pages had not been cut, meaning that no one had read it since its publication in 1797. In France, the only known library copy is held by the Bibliothèque municipale de Versailles (Rodouan A 431).

[8] In the limited and often dismissive scholarship on her work, she is typically referred to as “Elisabeth Brossin de Méré.” This appears to be inaccurate. Born Marie Guénard, she was consistently known during her lifetime as “Madame Guénard” a name used by contemporaries and early bibliographers well into the 19th century. No evidence has yet been found that she ever used the first name “Elisabeth,” nor is it used by those who knew her personally. Both names are retained here for the sake of clarity.

[9] See Luba Markovskaia, La Conquête du for privé. Récit de soi et prison heureuse au siècle des Lumières (Classiques Garnier, 2019) and Victor Brombert, La prison romantique. Essai sur l’imaginaire (José Corti, 1975).

[10] Cécile Tarjot, “Le récit sentimental pour imaginer la prison révolutionnaire, le cas de la ‘jeune captive’ et de son poète (Aimée de Coigny et André Chénier)” (unpublished). More generally, see her dissertation in progress, “La révolution sous les verrous : poétique et politique du récit carcéral (1789-1830).” All translations from French are my own.

[11] Anne de Mathan, Mémoires de Terreur : l’an II de Bordeaux (Presses Universitaires de Bordeaux, 2002), 42.

[12] Suzanne Giroust de Morency, Illyrine, ou l’écueil de l’inexpérience (Chez l’Auteur/Rainville/Mlle Durand/Favre/Les marchands de nouveautés, 1799-1800) vol. 3, 301.

[13] Giroust de Morency, Illyrine, vol. 3, 301.

[14] Marie/Elisabeth Guénard de Méré, Irma, ou les Malheurs d’une jeune orpheline ; histoire indienne (Chez Lerouge/Chez l’Auteur, 1799), vol. 1, 112.

[15] Félicité de Choiseul-Meuse, Coralie, ou Le danger de se fier à soi-même (Chez Chaignieau/Devaux/Vente/Deseine/Desjours/Chez tous les marchands de nouveautés, 1797), vol. 1, 118-119.

[16] Choiseul-Meuse, Coralie, vol. 2, 8-9.

[17] Giroust de Morency, Illyrine, vol. 3, 306.

[18] Choiseul-Meuse, Coralie, vol. 1, 123-24.

[19] For a historical study of the Terror and the notion of trauma, see Ronen Steinberg, The Afterlives of the Terror. Facing the Legacies of Mass Violence in Postrevolutionary France (Cornell University Press, 2019).