This post is a part of the 2025 Selected Papers of the Consortium on the Revolutionary Era, which were edited and compiled by members of the CRE’s board alongside editors at Age of Revolutions

By Irene Kim

Image 1. Attaque et débarquement anglais sur l’île d’Aix en 1757 et tentative de raid contre Rochefort. Guerre de Sept ans.

Around 4 and 5 o’clock in the late afternoon of 14 September 1758, HMS Essex cast its anchor in the harbor of the Aix, a small island of Rochefort which, like other Atlantic ports, had undergone a recent British siege at the height of the Seven Years’ War. The third-rate ship of the line obviously did not arrive with the intention of recommencing last year’s cannonade. Waiting for the northeasterly wind to dwindle down, the crew were anxious to dump 450 disease-ridden men and women back to where their ancestors had set sail five generations ago. Hardened and uncouth but bound by their almost fanatical devotion to the Catholic faith, some of the French-speaking prisoners were the living relics of Cardinal Richelieu’s proselytizing ambitions for Canada. The refugees would not have expected a frigid reception that rivalled their expulsion. Five years later, they found themselves reduced to ‘these Canadians who should not be allowed to return to their homeland.’[1]

How can one reconcile the continuity of heritage between the French and the Acadians and their ill-fated reunion? The 450 unfortunates included the first of the Acadian exiles to be shipped to France under the British flag after the fall of Île-Royale (Cape Breton Island) and Île-Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island) in the summer of 1758, who would continue trickling in with the eclipsing wartime fortune of France. The grand dérangement of 1755 has been eternalized by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Evangeline: A Tale of the Acadie (1847), but its second outbreak in 1758, as well as the years of tribulations following both deportations, are often subsumed under narratives of pilgrimage to Louisiana. Moreover, prevailing assumptions of intra-ethnic solidarity make it difficult to understand the double deracination of the repatriated. This paper, therefore, addresses these gaps by illustrating the immediate aftermath of an unprepared encounter, as well as its subsequent influence on the aggressively utilitarian policies of Duc de Choiseul, who eventually perpetuated the grand dérangement into the peripheries of the Atlantic.

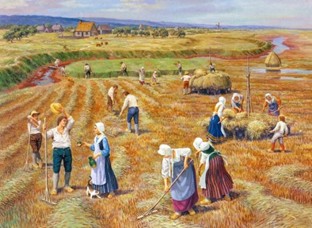

The Acadians were the population of predominantly French descent who had settled in the present-day Nova Scotia in the seventeenth century. In 1604, Sieur Pierre Dugua de Mons established the colony of la Cadie on an island in Passamaquoddy Bay, four years ahead of the foundation of Quebec by his accompanying geographer and cartographer Samuel de Champlain. Initially, geographical isolation and rich reserve of cod attracted seasonally migrant fishermen instead of trans-Atlantic settlers who became concentrated in the Lawrentian Valley. Administrative neglect from Paris even enabled a decade-long civil war between Massachusetts-allied Huguenot governor Sieur de La Tour and his Jesuit-backed contender D’Aulnay. The 300 original immigrants in 1632, tied to France by nothing but a few Catholic priests, flourished into a peripheral enclave with distinguishing features from both the mainland and the hubs of Nouvelle France. They included a more decentralized seigneurial hierarchy,[2] frequent intermarriages with the neighboring Mik’maqs,[3] and an overall primitive, unintriguing, and zealous demeanors in the eyes of the French visitors. In obscurity, Acadia prospered into a rustic commune by clearing out the salt marshes of the Bay of Fundy with the aboiteaux dikes imported from homelands in western France.[4] Even after the British takeover under the Treaty of Utrecht (1714) following the Queen Anne’s War (1702–1713), the habitants managed to outlive the fleur-de-lis by half a century. Tactfully temporizing the demands to sign the Oath of Allegiance to the British Crown, they retained their status as les français neutres[5] until it emerged as a security threat on the eve of the French and Indian War (1754-1763), which would kindle the Seven Years’ War across the Atlantic in 1756.

The Acadians’ tenacious resistance to the Oath led to the grand dérangement of 6,000 to the British colonies during the autumn of 1755, which continues to elicit sympathy and outrage in the francophone North America. But the much overshadowed second wave in 1758 showed a cold preponderance of wartime pragmatism over any ethnic solidarity in France. On 26 July 1758, after weeks of futile resistance, Governor Augustin de Boschenry de Drucour surrendered the garrison of Louisbourg to Major-General Jeffrey Amherst. To his shock, the British terms of capitulation dictated a complete evacuation of both Île-Royale and Île-Saint-Jean, including the civilians ‘that have not carried Arms…to France.’[6] Among them were the Acadians who had been spared from the deportation of 1755, only because they had migrated coerced and cajoled to migrate by Abbe Jean-Louis Le Loutre between 1749 and 1751. Forced to support the partisan resistance against the British Nova Scotia, they had reluctantly traded their farmsteads for the rocky, famine-stricken islands ‘where one does not see the sun sometimes for a month.’[7] Years of fruitless pleas for relief to the governors, themselves drained of budgets, left them destitute and languid, and a nuisance to the officials. One Monsieur de Varenne even came to justify the upheaval of 1755, that ‘it must be considered, that these people were absolutely [in]tractable as to the English,’ who could not ‘do otherwise than they did, in expelling their bounds a people, who were constitutionally, and invincibly, a perpetual thorn on their side…’[8]

No longer under scrutiny of political affiliation as in 1755, the remaining Acadians were destined for France alongside the prisoners of the Troupe de la Marine who would be exchanged for their enemy counterparts.[9] An incident following Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew Rollo’s capture of Île-Saint-Jean on 17 August consolidated the British resolve to clear all islands of habitants. As Admiral Boscawen later reported, the discovery of a few British scalps from the estate of Governor Villejouin in Port La Joie served as a proof that Île-Saint-Jean had ‘been an Asylum of all the French Inhabitants of Nova Scotia who had ‘constantly carried on the inhumane practice.’[10] While Rollo went on a capturing spree, HMS Essex embarked from Louisbourg on 18 August. Thus began the de facto re-expulsion of about 3,500 Acadians[11] to the westernmost French ports of La Rochelle, Rochefort, Saint-Malo, Cherbourg, Le Havre, Morlaix, and Boulogne-sur-Mer. Owing to the relatively little inflow of migrants, low infant mortality, and exceedingly high birth rate, the descendants of Richelieu’s pioneers made up roughly 2/3 of the Acadians.[12] Yet, their untimely homecoming to the disease-ridden, constantly shelled fringes of maritime France would invoke nothing but panic among the local officials completely unequipped to receive them. It was too late when Villejouin, himself a captive on one of the ships carrying the officers to England, sent notice to Versailles on 8 September.

All these wretched people will therefore, I believe, go to France. I dare to tell you their sad situation – it’s been three years since the last refugees were on the island. They had to endure many losses and fatigue to get there, and there they found themselves deprived, so to speak, of any help.[13]

The firstcomers to Aix on 14 September, composed of officers and Guards of the Marine, sailors, and ‘[p]eople from Île-Royale and elsewhere,’ were lucky enough to receive marginal accommodations and sympathy. Sieur Baudry, serving in the absence of Rochefort Intendant of the Marine Ruis-Embito, immediately sent fresh food to those on board and implored Marquis de Massiac, the Secretary of State for the Navy, to let him prepare for ‘such a sad reception’ by admitting the sick to the hospitals at the expense of feverish soldiers. Otherwise, he feared that ‘these islanders will suffer from a multiplicity of illnesses that could cause, by complicating the ills of the bad air that already reigns in the present season.’[14] On 19 September, they were released at Rochefort and headed for La Rochelle, where 63 sailors were exchanged for the similar number of British captives from Angouleme and Cognac.[15] Lacking immediate guidance from the Versailles and unaware of the nine other ships to follow Essex, Baudry improvised relief measures with remarkable alacrity, taking ‘every possible care to get housing by the city to those who landed here.’ It consoled him that ‘there have been very few [patients] so far,’ and that quite a lot, probably officers and soldiers with connections to the mainland, ‘intend[ed] to retire with their families’ in France.[16] His wishful expectations were betrayed by the arrival of the second ship, ‘La Marie,’ on the evening of the 22nd, after which the number of patients ‘increase[d] extraordinarily’ to 270.[17] Nevertheless, rations were distributed and foundries and seminaries, including ‘a special room’ to quarantine the ill, were opened for lodging.[18] Jean-Jacques-Blaise D’Abbadie, commissaire de la marine of La Rochelle, appears to have followed Rochefort’s example upon receiving his share of prisoners from both ships on the 28th.[19]

Contrary to their generosity, the state was determined to heavy-handedly economize the process of relief. Receiving the first letter from Baudry, Massiac replied on 21 September that Rochefort and La Rochelle must provide a ‘list of these families and their qualities, with all the clarifications [he] can get on what may have happened on the Île-Royale.’[20] The request indicated Versaille’s thorough ignorance of the loss of Louisbourg, which would only arrive on 2 October, and the homeless besides the prisoners. On 30 September, while communications with the ports were being stalled, Massiac added that those from Île-Royale must be categorized as follows: ‘families who have property in France and who can provide for themselves,’ ‘those who have a profession and can continue [practicing] it in Rochefort,’ those ‘who may be intending to move to another part of the Kingdom,’ and ‘the workers and fishermen who can be employed for their services.’[21] Only on 9 October did he acknowledge the existence of the fifth tier, ‘those who are absolutely unable to do anything and who are without resources.’ They were to be the sole beneficiaries of rations, vis-à-vis ‘those inhabitants who can provide for themselves.’ The phrase crossed out between ‘who’ and ‘can,’ decipherable as ‘need nothing,’ underlined his resolve to cut corners.[22] Reading those demands on 12 October, Ruis-Embito asked for Massiac’s patience, for it would take some time to list and classify the refugees who were spreading out between Rochefort and La Rochelle.[23]

Sympathy and prudence dissipated as the guests multiplied into 3,500 starving mouths. Just in two days, the belated news impelled Ruis-Embito to implement the new instructions as soon as possible. His warning to D’Abbadie on the 14th marked a drastic reversal from his cordial pleas to Massiac in September. For the ‘habitants of Île-Royale who are in a position to earn their living working in the port,’ rations were to be terminated a week after their arrival.[24] When the 10th ship approached La Rochelle on 26 October, Ruis-Embito became completely aligned with the stringent outlooks of Massiac. ‘We are ruining ourselves in every way, and we can’t help it,’ he noted on the very day. That 90 out of 440 passengers had died from diseases during their voyage must have made their presence especially revolting. Rochefort was out of hospital beds,[25] especially for women, for whom there was ‘no other establishment than the orphans’ hospital’ with ‘only 12 beds.’[26] But he turned down Massiac’s suggestion to convert the naval arsenal of Aix to a hospital and sent the excess patients to D’Abbadie. The decision, while in consideration of avoiding inviting English raids, markedly differed from his earlier plan to lodge the habitants in place of the sick soldiers. Among those unaffected, guidance was offered to anyone wishing to resettle elsewhere, for ‘[t]his expense was less than the cost of maintaining them.’ Most importantly, for the healthy wishing to stay where they were, Rochefort set the precedent for the policy that would permanently torment the Acadian refugees. The heads of such families were drafted to the Arsenal de Rochefort, upon which they were removed from the rationing list. Only every family with more than two children would receive ‘6 to 7 [sols] per head,’ which would amount to ‘quite a big saving.’[27]

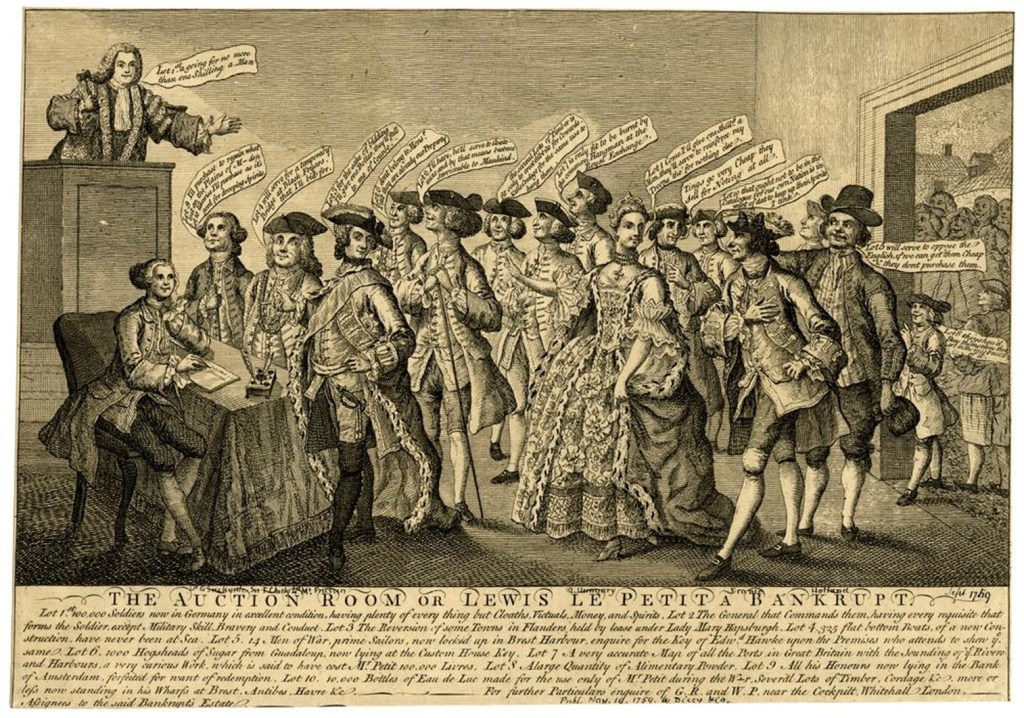

On 30 December 1758, when the newly arriving spread out into the ports of Cherbourg and St. Malo, Massiac’s successor Nicolas-René Berryer systemized Rochefort’s experiment into a three-tiered relief that relegated the Acadians to onerous dependents; or, he legally reaffirmed of their burdensome status in the garrison of Louisbourg, for not only Ruis-Embito but also Prévost, the former commissaire général de la marine of Île-Royale, had been consulted. First, all officers from Canada were to ‘continue to enjoy their salaries and wages as if they were doing their services and working in the colony.’ Second, sailors and soldiers of the Marine were to be sent home with due payment. Then came the declaration for the ‘habitants and the common people’:

[A]ll those who can be useful must be made to work in the ports for the royal service, paying them at the normal prices and in cash in order to give them the means to subsist, but without yet granting them the ration, and for those who are absolutely poor and unable to do anything, they must be given six sols per day per person until further notice.

It was a guise of magnanimity from the court dwindling in bankruptcy amidst the losing global war. The hierarchy of productivity disregarded the difficulty of finding work in Bourbon France ‘in which guilds and compagnonnages regulated labor.’[28] Their occupations were limited to menial and easily substitutable jobs-ploughmen (laboureur) and coaster (caboteur) for men and laundress (blanchisseuse) for women.[29] On top of this, the six sols proved extremely meager compared to the other royal subsidies. The nuns from the same islands, who were sent to assist the hospitals of La Rochelle, were given 12 sols a day, and the missionaries arriving at Cherbourg 20 sols a day with promises of ‘same assistance’ to the others ‘who will still be able to return to France.’[30] A more striking comparison is the 6 sols granted to the Alsatian families at Rochefort who had been waiting to emigrate to Louisiana. In 1756, they followed their family who had been sentenced to a trans-Atlantic exile for their Lutheran faith three years ago, only to be intercepted by the British en route.[31] Despite their status as religious dissidents, that they were ‘mainly composed of women and children who cannot work’ justified the distribution of pension equal to that for the unemployed Catholics.[32]

The Acadian crisis reached its full swing as more and more swarmed into the ports bereft of funds and jobs. The édits bursaux terminating the circulation of public funds left the local bakers refusing to spare their bread in fear of not being reimbursed by the officials. Only then did it dawn on Ruis-Embito that six sols would never suffice for minimum living conditions. In vain, he warned Berryer that ‘rumor is rife that some have died of hunger’ in Rochefort and La Rochelle and begged him to guarantee a day’s wage of at least 16 sols to each father working as a day laborer.[33] The concurrent resurgence of smallpox at the end of the year wreaked havoc on those withered by the voyage,[34] some of whom were sent to the parish graveyards almost immediately after landing on the French shores.[35] Ladvocat de la Crochais, a St. Malo lawyer who was hosting 22 refugees in his farm, even implored commissaire de la marine Frédéric Joseph Guillot to consider ‘the sacrifice [the Acadians] have made of all their possessions in order not to leave the service of France.’ He was certain that without his help, ‘these unfortunate people,’ 17 of whom were women and children, ‘would have lacked the necessities and remained like those who are a league from here in this parish, all sick and several already dead.’[36]

Berryer, however, was determined not to intervene more than keeping as many employed as possible. Such callous pragmatism becomes transparent in his exchanges with Armand-François de Chanlaire, commissaire des classes of Boulogne, who first encountered the refugees in early 1759. That January, Berryer urged him to ‘get rid of them as soon as possible’ by sending them off to factories or lands in need of cultivation around Amien. Crossed out was his condescending remark, ‘that they do not know any professions other than ploughman.’[37] In March, he conveyed his reservations against Chanlaire’s proposal to occupy the women with fabric trades, citing cost of materials and the waiting period before sales. Instead, he recommended embarking their young men on ‘the King’s corsairs or frigates,’ for ‘they are not prisoners.’[38] They were, in fact, rendered such by the government set on integrating them to the lowest denominator of the society. Irked by their refusal a week later, Berryer ordered the commissaire to ‘exclude from them the help that the King gives them.’ The end of his letter summarized his perception of the Acadians as excess unskilled labor to be disposed of at the first opportunity:

If, on the one hand, the intention of His Majesty is to relieve these families, it is necessary, on the other hand, to reduce this expense as much as possible, especially by employing the habitants in a useful way.[39]

The Acadians reacted by wandering from one port to another in search of whatever work. Such only intensified surveillance of recurrent payments of pension, which were reported from Cherbourg, Le Havre, and St. Malo in mid-1759. Berryer ordered their officials to track down all such movements to prevent duplicate listings for six sols and not to promote ‘transmigrations’ lest the refugees become accustomed to vagrancy.[40] The Cherbourg refugees were only yearning for the war to be over in order to return to Canada, which led to their petitions to allow cousin marriages, for ‘a wife from the country [France] would not want to follow.’[41] Berryer’s exhaustion is evident in his note of approval to grant such couples dispensations—‘It is worth preventing this inconvenience.’[42] In other words, it would be a win-win to have them gone in a few years. Despite all the exhortations, he did not stop accusing the Acadians of avoiding work to live off their 6 sols.[43] Blaming ‘the habits [of idleness?] they have acquired’ in France, he virtually terminated all relief on 29 July 1761.[44]

An illusion of rescue came when the tide of the Seven Years’ War had turned irrevocably against France with the defeats at the Plains of Abraham (1759), Qiberon Bay (1759), and Pondicherry (1761). Berryer’s successor Duc de Choiseul restored the six-sol-pension on 14 November 1761, followed by the initiative to repatriate the remainder of the Acadian prisoners from the British Colonies and England. But there was no room for unconditional charity in a war-weary regime plunged into the debt of 2,300 million livres, about twofold that of 1753.[45] While he did not ‘want to see the Acadians perish from poverty,’ [46] he proved just as brutally realistic, if not more creative, as his predecessor. If Berryer had wished them to go back to the lost colonies, Choiseul’s circle flirted with the wildest ideas of sending them to where they would be made best use of. On 26 December 1761, the duke announced his final plan to the ports which had been burdened with the refugees:

The expense which costs the King, Sir, the Acadian and other families of North America who are withdrawn to your department being a pure loss for His Majesty… theirs will continue during the first quarter of next year, after which time they will no longer enjoy the 6 sols per head which have been granted to them. However, as I foresee that after this term most of these families would perhaps still find themselves exposed to poverty, you will be able to foresee in advance that those who wish in this interval to move to Cayenne, to Martinique, to Sainte-Lucie, in Guadeloupe or in Saint-Domingue will continue to enjoy the same grace that his majesty gave them in France.[47]

On 4 April 1763, Versailles was beset with a wave of petitions for ‘the freedom to return to Acadia and Canada,’[48] preferably the Islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon, or to ‘stay in France and renounce the benefits from the King.’[49] The only alternatives, however, turned out to be joining the exploration of Îles Malouines (the Falkland Islands) or cultivating Belle‑île-en-Mer, a constantly flooded island of Brittany torn by incessant change of hands since the mid-17tn century.

The authorities suppressed their grievances with unprecedented ruthlessness. Controller General of Finance Henri Bertin, frustrated by those resisting the demands to move to Cayenne, suggested ‘sending them to work in the mines.’[50] His note to Intendent Fontette of Caen derided the Acadians as ‘these Canadians who should not be allowed to return to their homeland,’[51] a sentiment which Choiseul concurred with gleefully: ‘I will not hide from you that I would be very happy to see them make this determination [to leave], they cause a considerable expense in France without any occupation.’[52] The grand dérangement, after all, was never over, for reunion with long-lost kins remained a luxury on the war-ravaged soils.

Irene Kim is an independent historian and a former strategy consultant based in Seongnam, South Korea. Born in 1993, she majored in International Relations at Yonsei University and Yonsei Graduate School of International Studies. Her areas of focus are 18-19th century Europe and North America, with a bias for Nouvelle France and the later period of the Napoleonic Wars. Currently, she is writing Voices from 1812, a three-volume daily chronicle of the Russian Campaign of 1812, to be published by Helion & Company.

Title Image: Joseph Vernet, View of Rochefort Harbor, from the Magasin des Colonies.

[1] Bertin to Fontette, 23 June 1763, AD Calvados [Caen], C 1019.

[2] Naomi E. S. Griffths, From migrant to Acadian: a North American border people, 1604-1755 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005), 34, 47-9, 64-5; Andrew Hill Clark, Acadia: the geography of early Nova Scotia to 1760 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1968), 90-96, 114-5, 118-9; John Bartlet Brebner, New England’s outpost: Acadia before the conquest of Canada (New York: Burt Franklin, 1928), 37-39, 43-44.

[3] See Sieur de Diéreville, Relation du voyage de Port Royal de l’Acadie ou de la Nouvelle France, in Ludger Urgel Fontaine, ed., Voyage du Sieur de Diereville en Acadie (Quebec, 1885), 45-6.

[4] Christopher Hodson, The Acadian Diaspora: An Eighteenth-Century History (Oxford University Press, 2012), 26-7.

[5] The term continued to be in use as late as in the 1750s and 1760s; see John Thomas, Diary of John Thomas, in John Clarence Webster ed., Journals of Beauséjour: Diary of John Thomas, Journal of Louis de Courville (New Brunswick, Sackville: The Tribune Press, 1937), 18; John Salisbury, Expeditions of Honour (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2011), 154; Winslow to Monckton, Grand Mines, 22 August, 1755, in Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society 3 (1883): 71.

[6] ‘Copy of Journal kept by —Gordon, One of the Officers engaged in the Siege of Louisbourg under Boscawen and Amherst, in 1758,’ Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society 5 (1886–87), 142.

[7] Chevalier de James Johnstone, Memoirs of the Chevalier de Johnstone: Adventures after the battle of Culloden (Aberdeen: D. Wyllie & Son, 1871), 178.

[8] Monsieur de la Varenne and Ken Donovan, “A Letter from Louisbourg, 1756 (with an introduction by Ken Donovan),” Acadiensis 10, no. 1 (1980): 126-7.

[9] Jean-Franois Mouhot, “Les habitants des iles Saint-Jean et Royale,” Chapitre 1, in Les réfugiés Acadiens en France, 1758-1785: l’impossible réintégration? (Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2012), Kindle.

[10] Boscawen to Pitt, 13 September 1758, CO 5/53, pp. 123-5, cited in Earle Lockerby, “Deportation of the Acadians from Ile St-Jean, 1758,” Acadiensis 27, no.2 (1998): 71-2.

[11] Lockerby, 48-76; Mouhot, “Les habitants des iles Saint-Jean et Royale”; A. J. B. Johnston, Endgame 1758: The Promise, the Glory, and the Despair of Louisbourg’s Last Decade (University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 276.

[12] Clark, Acadia, 123, 129, 131; Brebner, 38; Griffths, The Contexts of Acadian History, 48; Edme Rameau de Saint-Père, Une colonie féodale en Amérique: L’Acadie, 1604-1881, T. 2 (Paris, 1889), 350-1; Clark, Acadia, 131.

[13] Villejoin to Massiac, 8 September 1758, Archives Nationales de France, fonds des Colonies (hereafter ‘AN Col’) C 11 B 38 fol.165-167.

[14] Baudry to Massiac, 16 September 1758, Service Historique de la Marine (Hereafter ‘SHM’) Rochefort 1 E 414, n° 498.

[15] Baudry to Massiac, 30 September 1758, SHM Rochefort, 1 E 414, n° 510.

[16] Baudry to Massiac, 19 September 1758, Archives de la Marine (hereafter ‘AM’) Rochefort, 1 E 414, n° 502.

[17] Baudry to Massiac, 23 September 1812, SHM Rochefort, 1E 414, n° 505.

[18] Baudry to Massiac, 19 September 1812, AM Rochefort, 1 E 414, n° 502.

[19] Massiac to D’Abbadie, 9 October 1758, AN Col B 108, Folio 107 ½.

[20] Massiac to D’Abbadie, 21 September 1758, AM Rochefort, 1 E 160, f 625.

[21] Massiac to Ruis-Embito, 30 September 1758, AN Col B 108, Folio 102.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ruis-Embito to Massiac, 12 October 1812, SHM Rochefort, 1 E 414, n° 521.

[24] Ruis-Embito to D’Abbadie, 14 October 1758, SHM Rochefort, 1 E 414, n° 521.

[25] Ruis-Embito to Massiac, 26 October 1758, SHM Rochefort, 1 E 414, n° 562.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Hodson, 97.

[29] Berryer to Ruis-Embito, 26 May 1759, Archives du Port de Saint-Servan, C 8, Liasse 7 (C 8 / 7).

[30] Berryer to L’Isle Dieu, 11a December 1758, AN Col B 108.

[31] Glenn R. Conrad, “L’immigration alsacienne en Lousiane, 1753-1759,” Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française 28, no. 4 (1975): 574.

[32] Ruis-Embito to Berryer, 21a November 1758, AM Rochefort, 1 E 414, lettre n° 611.

[33] Ruis-Embito to Berryer, 26 December 1759, SHM Rochefort, 1 E 415, n° 726.

[34] Mouhot, “Déportation des îles Saint-Jean et Rotale,” Introduction, in Les réfugiés Acadiens en France; Ernest Deseille, “Les Canadiens (Acadiens) de rile St.-Jean a Boulogne 1758-1764”, La societe historique acadienne: les cahiers, IV, 5 (avril, mai, juin 1972), 203, cited in Lockerby, 80.

[35] 1758-21-10 // 1758-11-15, AD Charente-Maritime (La Rochelle), 3 E 33-80, notaire Mérilhon père, année 1758.

[36] Ladvocat de la Crochais to Guillot, 10 May 1759, SHM Brest 1 P1.

[37] Berryer to Chanlaire, 12b January 1759, AN Col B, vol. 110.

[38] Berryer to Chanlaire, 10c March 1759, AN Col B, vol. 110.

[39] Berryer to Chanlaire, 23 March 1759, AN Col B, vol. 110.

[40] Berryer to Guillot, 10 August 1759, AN Col B, vol. 110; Berryer to Ranché, 12 October 1759, AN Col B, vol. 110; Berryer to Guillot, 10 August 1759, AN Col B, vol. 110.

[41] Acadians of Cherbourg, 18c September 1759, AD Manche, Saint-Lô, 6 Mi 252 to 257.

[42] Berryer to Abbé de L’Isle-Dieu, 15 December 1759, AN Col B, vol 110.

[43] Berryer to Ranché, 17 August 1760, AN Marine B3 vol. 547, folio 131.

[44] Berryer to the administrators of the Marine, 29 July 1761, AN Col F3, vol. 16.

[45] The figure is for the year 1764; the global scale of the war, as well as Silhouette’s tax policy, exacerbated the financial strain in Paris. See James C. Riley, The Seven Years War and the Old Regime in France: The Economic and Financial Toll (Princeton University Press: 1986), 183-4, 148-153.

[46] Choiseul to Port Commissioners, 14 November 1761, AN Col B 113.

[47] Choiseul to Intendents and Commissaries of the port, 26a December 1762, AN Col B 115.

[48] Choiseul to Bertin, 4 April 1763, AN Col B 117, folio 117.

[49] 1764-00-00b, AN Col G1 512.

[50] Marion F. Godfroy, Kourou and the Struggle for a French America (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 100.

[51] Bertin to Fontette, 23 June 1763, AD Calvados [Caen], C 1019.

[52] Choiseul to the Municipal Council of Morlaix, 18 June 1764, cited in Jean Ségalen, “L’odyssée de la communauté acadienne de Morlaix,” Les Amitiés Acadiennes 64, (1993), 1178.