By Kathleen Telling

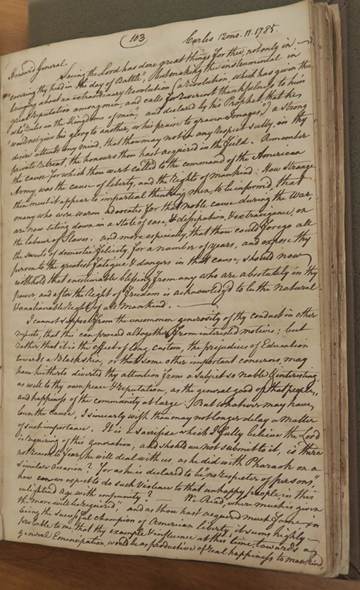

In 1785, Robert Pleasants, a wealthy tobacco planter, abolitionist, and prominent member of Henrico County’s Quaker community, penned a letter to Virginia’s most famous son, George Washington. Addressing him as “Honour’d General,” Pleasants reflected on the divine favors that had not only granted Washington success in his efforts to secure the United States’ liberty but had also granted Washington a “great reputation among men.” Yet for all of Washington’s grand feats, Pleasants feared that the great man’s legacy was in danger.

Letter from the Pleasants to Washington

The concerned Quaker, or Friend, urged Washington to remember that he had lately risked his life for the glorious cause of liberty. Strange then, Pleasants mused, that he should return home and rest in “a state of ease, dissipation, and extravagance on the labor of slaves.” How could a man such as Washington, Pleasants wondered, a man who had been prepared to lay down his life in the name of liberty, be capable of denying that “inestimable blessing” to those who were “absolutely in [his] power.” By championing emancipation, not only would Washington resolve this glaring hypocrisy, but his efforts would surely be honored as “crowning the great acts of his life.” Pleasants concluded by acknowledging that the “Honour’d General” may find such a frank address from a mere acquaintance to be presumptuous. However, his convictions that the moral health of the retired general and the nation were at stake compelled him to be bold. Washington’s response–if he supplied one at all–is unknown.[i]

If Washington was affronted, he would perhaps have been able to console himself with the knowledge that he was not the only prominent Virginian to receive such a direct note from Pleasants. In 1791, one year after launching the Virginia Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery as a founding member, Pleasants wrote to then Congressman James Madison soliciting his support for a petition to introduce a bill of gradual abolition in the House of Representatives. Perhaps Madison’s apparent ambiguity about slavery’s longevity gave Pleasants reason to believe he would find an ally in his fellow Virginian. Echoing his earlier appeal to Washington’s sense of legacy, Pleasants invited Madison to consider how “noble” it would be for a man such as he, “favored with abilities and influence,” to act as a friend to the “ignorant, injured, and helpless.”[ii] Madison replied to Pleasants that it would not be prudent to introduce the petition as it would constitute a breach of the trust (a “public wound,” in his words) with his many pro-slavery constituents who had put him in office.[iii]

Undeterred by Madison’s dismissal, Pleasants reached out to Thomas Jefferson in 1796 to request Jefferson’s support in establishing a free school for both free and enslaved Black children. Knowing Jefferson’s long held support of public education, Pleasants characterized the man as “a real friend to the true cause of liberty and endowed with ability and influence in regulating and promoting suitable plans for such a purpose.”[iv] Jefferson, though cordial in his reply, ultimately decided against throwing his support behind a plan that would bring enslaved children in regular contact with free Black children. Friend of liberty he might he have been (and certain that “ignorance and despotism seem made for each other”), Jefferson argued that to educate those who he believed could never be fit for freedom was simply at odds with their happiness.[v]

Embedded across these exchanges was the language of contested manhood in early Republic Virginia. Though Pleasants employed the usual religious rhetoric of late eighteenth and nineteenth-century moral reformers, he was careful to include specific overtures to each man’s understanding of himself as a civic leader. As wealthy white planters and patriarchs, Pleasants and his correspondents occupied similar positions of Southern social power that largely went unchallenged during and after the American Revolution. Each man was also steeped in a Revolutionary and Republican culture of expectation for white Southern men–Virginians, especially–to shape the new nation. An anonymous 1777 appeal in the Virginia Gazette urging young men not to lose heart was characteristic of this legacy-minded manhood: not only would Continental soldiers be venerated in the present day, the author argued, but their efforts would have the added benefit of “fixing on Virginians the glorious and envied epithet of brave.”[vi] Although Pleasants was preempted from Revolutionary service by his fierce devotion to pacifist Quakerism and men such as Washington, Madison, and Jefferson were held as the models to which Southern men should aspire, all men were intimately invested in the country that would emerge from Revolutionary efforts. Moreover, each man’s manhood was intimately tied to the long uncontested expectation that dominance was the proving ground upon which white Southern manhood was built. Their differences lay in how they performed masculinity and the stakeholders to whom they were ultimately beholden.

Virginia Society for Promoting the Abolition of Society, Virginia Gazette, 1790, Virginia Museum of History and Culture

Pleasants’ pleas to Washington, Madison, and Jefferson were borne out of a mid- to late-eighteenth century push to cleanse American Quakerism of worldly influences. Following advice issued by the Pennsylvania Yearly Meeting in 1774, Quakers across the former British colonies concluded that they could no longer reconcile the Quaker Peace Testimony with the inherent violence of slavery. The legal roadblocks to manumission, especially those within the Southern states, compelled Quakers to lay aside their historic aversion to appearing in court and more recent aversion to the formal world of public politics and challenge the laws preventing them from fulfilling the dictates of their faith.

Pleasants was a fitting choice to act as a liaison between Virginia Quakers and the planter elite. Having long served as an active member of and clerk for Henrico Monthly Meeting of Friends, provided necessary funds for his community’s affiliate Meeting for Sufferings, and now aged into the role of a respected meeting Elder, Pleasants was by all counts a religious patriarch. And as his voluminous records of family correspondence attested, he was more than comfortable offering his advice (solicited or otherwise) on his real and virtual relations’ concerns. He could also reach out to the gentry class as a fellow member of the Virginia elite. The Pleasants name had been in Virginia as early as the 1660s, when the first John Pleasants settled in what became Henrico County, converted to Quakerism, and purchased the land upon which he built the family plantation, Curles Neck, conferring wealth and status upon succeeding generations of Pleasantses. Quakers were expected to live modestly and be wary of accumulating riches: but it was wealthy Quakers, often enslavers in the South, whose fortunes supplied poor relief, paid for meetinghouse repairs, and reassured their antagonistic neighbors that Quakers would not become a drain on public resources. Quaker men were expected to provide, regardless of the source from which they drew their provisions.

To engage men such as Washington, Pleasants had to carefully navigate the varied and often contradictory expectations of him as both a Southern and a Quaker man in the early United States while appealing to elite Virginian men’s manhood in turn. Pleasants’ wealth, claim to an early family presence in Virginia, and extensive landholdings confirmed his status as the ideal planter-patriarch easily capable of providing for his numerous relations. But his fierce devotion to a dissenting religion marked him and his coreligionists as irregular, even unmanned. Well before the emergence of an evangelical masculine ideal that prized “piety, sobriety, and nonviolence,” Southern Quaker men were beholden to masculine standards at direct odds with those generated by their religious convictions.[vii]

Long before the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, Southern Quaker men were thorns in the sides of royal officials and provincial legislatures alike. As pacifists who couldn’t serve militias, join in raids against Indigenous nations, or aid efforts to capture those who self-emancipated–all means by which white Southern men proved their manliness–Quaker men were unable to serve British imperial interests in a conventionally masculine way. More recently, Thomas Paine’s “Epistle to Quakers” castigated Friends for refusing to support the Patriot cause. Quakerism, Paine argued, had the “direct tendency to make a man the quiet and inoffensive subject of any.” Rather than take an active part in history, Quaker men “quietly and passively resigned” themselves to every changing government. It wasn’t just that the neutral Quakers were opportunistic fence sitters in Paine’s view; functionally, they were women.[viii]

Presumably, the sort of manly civic engagement that critics such as Paine hoped Quaker men would engage was not a nearly single-minded focus on abolitionism. Quakers like Pleasants were stepping boldly into the civil sphere, a critical component of the new American manhood, but they were doing so in service of an ideal that fundamentally threatened the racial power structures undergirding Southern (and, frankly, American) society. Nor did Pleasants’ legal activism and political overtures signal his embrace of the recent all-important emphasis on manly individualism: beholden to an intensely communal religious tradition and disinterested in occupying a position of formal political power, Pleasants represented the longevity of community identity. Though Southern evangelicals were forging an alternative expression of humane masculinity, Pleasants and other Quaker men’s antislavery efforts nonetheless marked their politicking as distinctly outside the Southern masculine racialized norm. A contested vision of white male public performance.

Contested, but not marginalized. All three of Pleasants’ correspondents and Pleasants himself were caught in the conflicting expectations of white Southern manhood in the early Republican era. The former fought in the name of everyman republicanism as members of the aristocratic planter elite. The latter developed a civic persona entirely premised on the destruction of one of the pillars that confirmed his own elite status even as he continued to benefit from his familial and personal investment in slavery. Each man determined what was an acceptable expression of their manhood in accordance with their regional, religious, and class contexts. What was immutable, though, was the ever-present tacit understanding that white Southern masculinity was defined by the ability to exert power over others and to leave a public legacy that would long outlive them. Though Pleasants urged Washington not to rest on the extravagant oppression of those he enslaved, the comfort he felt in addressing the leading member of Virginia society was enabled by the hundreds of enslaved from whose labor Pleasants and his family drew their fortunes. Nor did he (much like many of his fellow Quakers) dispute the belief that white men were most fit to occupy spaces of authority and directly shape the nation’s future, whether in reform work or formal politics. Like Washington, like Jefferson, Madison, and all other members of the Virginia gentry class, Pleasants faced a new nation that was at once new and entirely familiar. The notion that white men should not be in control went virtually uncontested by those who wielded its social power. But the inconsistencies and instabilities of what that control should look like were inherent in the character of the new American man.

Katy Telling is an historian of the family, household authority, and Quakers in the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century American South. She received both her PhD (2025) and MA (2019) in History from the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. She is currently the Postdoc 2026 Coordinator at the John Carter Brown Library. Telling serves as a board member of the Friends Historical Association and as the Productions Editor for Commonplace Journal. Her BlueSky handle is @katytelling.bsky.social.

Title Image: George Washington by James Peale. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Further Readings:

Bienstock, Barry, Annette Gordon-Reed, and Peter Onuf, eds. Family, Slavery, and Love in the Early American Republic: The Essays of Jan Lewis. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021.

Carruthers, A. Glenn. Quakers Living in the Lion’s Mouth: The Society of Friends in Northern Virginia, 1730-1865. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2012.

Glover, Lori. Southern Sons: Becoming Men in the New Nation. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2007.

Hardin, William Fernandez. “This Unpleasant Business’: Slavery, Law, and the Pleasants Family in Post-Revolutionary Virginia.” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 125, no. 3 (2017): 211-246.

Soderlund, Jean. Quakers and Slavery: A Divided Spirit. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014.

Endnotes:

[i] “Robert Pleasants to George Washington, 11 December 1785,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-03-02-0384. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Confederation Series, vol. 3, 19 May 1785 – 31 March 1786, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1994, pp. 449–451.]

[ii] “Robert Pleasants to James Madison, 6 June 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-14-02-0024. [Original source: The Papers of James Madison, vol. 14, 6 April 1791 – 16 March 1793, ed. Robert A. Rutland and Thomas A. Mason. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983, pp. 30–31.]

[iii] James Madison to Robert Pleasants (October 30, 1791). (2021, April 05). In Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/primary-documents/letter-from-james-madison-to-robert-pleasants-october-30-1791

[iv] Robert Pleasants to Thomas Jefferson (June 1, 1796). (2020, December 07). In Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/primary-documents/letter-from-robert-pleasants-to-thomas-jefferson-june-1-1796.

[v] “Thomas Jefferson to Robert Pleasants, [27 August 1796],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-29-02-0135. [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 29, 1 March 1796 – 31 December 1797, ed. Barbara B. Oberg. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002, pp. 177–178.]

[vi] A Soldier, “Fellow Soldiers,” Virginia Gazette [William Parks], February 5, 1777, History Commons.

[vii]Janet Moore Lindman, “Acting the Manly Christian: White Evangelical Masculinity in Revolutionary Virginia,” William & Mary Quarterly vol. 57, no. 2 (Spring 2000): 393-416.

[viii] Thomas Paine, “Epistle to Quakers,” from Bradford’s 3rd edition of Common Sense, 1776, The Thomas Paine Historical Association. https://www.thomaspaine.org/writings/1776/epistle-to-quakers.