By Nicolai von Eggers

The Haitian Revolution, which began when a revolt broke out 1791 on the Northern Plain in the French the colony of Saint-Domingue, ultimately led to the abolition of slavery and the creation of the first Black-led independent state in the Western Hemisphere. Nonetheless, scholars have struggled to determine what the first wave of revolutionaries originally sought to achieve. Was it independence and emancipation? Or were the aims merely improved working conditions and greater security? Or was it something in-between?[1]

Among the early revolutionary leaders was Jeannot Bullet, a figure shrouded in controversy and portrayed in historical accounts as excessively violent. Jeannot was executed a couple of months into the insurrection by a fellow revolutionary leader, Jean-François Papillon, and the historiography has almost unanimously explained the execution as due to Jeannot’s violence.[2]

However, a deeper investigation into the execution reveals a more complex story of division and of competing political visions within the revolutionary movement. Revisiting the execution of Jeannot will thus allow us to rethink what we know about the political ideals of the first wave of Haitian revolutionaries and the internal divisions of the revolutionary movement.

The Execution of Jeannot

Scholars have often attributed Jeannot’s execution on November 1, 1791, to his alleged brutality. The execution is described in multiple accounts that all portray Jeannot as a cruel and monstrous figure. Yet, although we apparently have a handful of contemporary descriptions of Jeannot, there is much to suggest that they all rely on a single source: the eye-witness account of Gabriel Le Gros.

Gros was a white Frenchman enrolled in the local militia. Jeannot’s revolutionary guerrillas captured him after a confrontation in late October 1791. Gross witnessed how Jean-François alongside Jeannot, one of a half-dozen leaders of the revolutionary guerrilla war, arrived in the camp and executed Jeannot. Gros claimed that Jean-François ordered Jeannot’s execution due to his brutality, promising to spare white prisoners and maintain order. Gros claimed, “Jean-François, the general in chief, who was known to be more humane, had become irritated by Jeannot’s cruelty and had him arrested and taken to Dondon, where he was shot the same day.”[3]

However, Gros’ account, which was subsequently published in 1792 and 1793 in various French and English editions in Saint-Domingue, France, and Baltimore, is far from trustworthy. Gros went on to work for Jean-François as his personal secretary and thus had personal motives to present Jean-François favorably, as he served in his inner circle and subsequently sought to justify to his white audience his own actions during captivity. This begs the question: Could there be other reasons as to why Jean-François killed a fellow revolutionary leader?

Competing Revolutionary Strategies

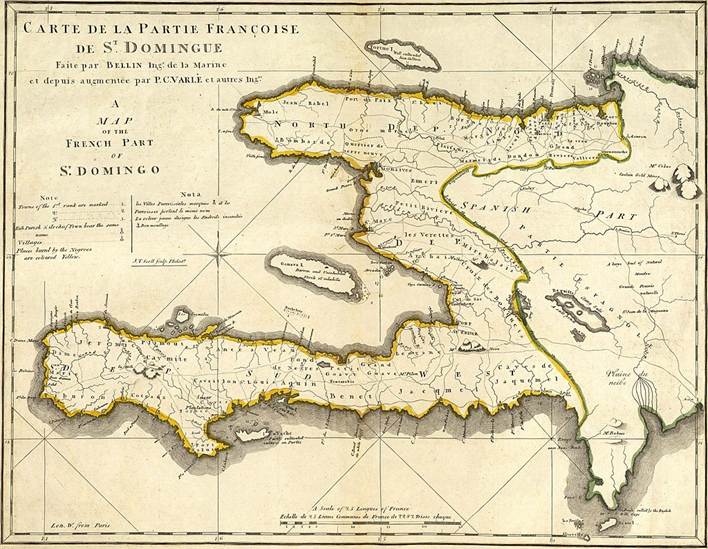

There is much to suggest that questions of strategy divided the early Haitian revolutionary movement. After an uprising broke out on Saint-Domingue’s Northern Plain in late August 1791, tens of thousands of people joined the uprising. They were in an area of about 2000 km2, mostly in the mountains and hills surrounding the Northern Plain. Different areas thus had different leaders who organized the troops and oversaw large operations that included women and children.

Map of Saint-Domingue, 1789 (Wikipedia)

Jeannot emerged as one of the most skilled generals in the early fighting. On 27 August, he took the strategically important town of Grande-Rivière, which provided a link between then plain and the mountains, and on 10 September, he secured the mountainous town of Dondon, which was important for securing lines of provision to Spanish Santo Domingo. From his mountainous stronghold, Jeannot conducted regular raids onto the plain – Jeannot himself on horseback leading a small cavalry of revolutionaries – and managed to hold certain parts of it for shorter periods of time.[4]

A letter dated 15 October 1791 from Toussaint Louverture – who still remained in the background of the revolution at this point – to one of the rebel leaders, George Biassou, reveals that the uprising at this moment revolved around the strategy of conquering Le Cap, the main city of the Northern Plain and a crucial port, and thereby take complete control over the region. Such a strategy would almost undoubtedly have involved the complete abolition of slavery. Or, as Jeannot put it in a letter to the leader of the French army, General Philippe François Rouxel, viscount de Blanchelande:

Abandon Le Cap. Let them [the French] carry off their gold and their jewels. We are seeking only that dear and precious object, freedom. That, General, is our statement of our beliefs, which we will uphold with the last drop of our blood. We lack neither gunpowder nor cannons. So: Liberty or death![5]

Revolutionary leaders such as Dutty Boukman, Paul Blin, and Jeannot seem to have been the most ardent pursuers of this strategy of fighting for complete control over the plain until death, which is what happened. On 1 November, fellow revolutionary leader, Jean-François killed Jeannot. A few days later, Paul was killed by “the leaders of the revolt,” according to a member of the white militia and one of the first historians of the revolution, Antoine Dalmas.[6] Some have interpreted the “leaders of the revolt” to signify Jeannot, but since he was already dead, it is likely that the perpetrators were Jean-François and Biassou.

Only a few days after Paul’s death, Boukman suffered the same fate. He died of more “natural” revolutionary reasons, during a battle with the French. However, more than a month before, the director of one of the plantations claimed to have found a note ordering the execution on Boukman on another revolutionary leader killed in battle. As the manager of the Clément plantation put it in his manuscript:

In the pocket of Georges, who was one of the leaders of the revolt whom we had killed, we find a note with the following words: “I give the power and ordain to Georges, general major of my cavalry, to kill Bouqman and Paul wherever they may be, signed Jean-François King.” What motives cold the highest commander of the black army have to send out a such order?[7]

What motives, indeed? By the end of the November, the rest of the revolutionary leadership had been exterminated, leaving Jean-François and Biassou in charge of the operation.

Shortly afterwards, still in November, Jean-François and Biassou took up negotiations with the French. The demands were no longer “liberty or death.” Instead, in a letter to Lieutenant Colonel Annie-Louis de Tousard, the revolutionary leaders proposed the following:

1. pardon for the officer corps [revolutionary leaders] and the legal registration of their freedom,

2. general amnesty for all the enslaved,

3. freedom for the leaders to withdraw wherever they wish

4. full enjoyment of the effects in their possession[8]

In subsequent letters, Jean-François and Biassou also bargained for improved working conditions for the enslaved population in Saint-Domingue. The French refused, and the Haitian Revolution ultimately continued.

The Fall of Jeannot’s Vision

By the end of the fall, the revolutionary leadership had thus changed, and the strategy and the aims of the revolutionary shifted significantly alongside this change. The aim was no longer general emancipation or even independence. It was freedom for the leaders and vague promises of improved conditions for the rank and file.

Were Jean-François and Biassou simply being pragmatic? With many of the early leaders gone and with a hitherto failed strategy of taking control of the Northern Plain, were they not simply putting forth a more realistic plan that could ensure the uprising did not lead to anything? Although we cannot be sure, there is much circumstantial evidence to suggest that Jean-François and Biassou purged the revolution of rival leaders with rival visions. Consequently, their “pragmatic” strategy was not a question of adapting to circumstances but a premeditated plan that involved assassinating other key figures in the movement. What is more, we should not necessarily assume that Jeannot’s plan for general emancipation and independence was entirely utopian. In fact, there is an argument to be made that Jeannot was pursuing his strategy (supported by Paul and Boukman, it seems) from a position of relative strength.

In his description of his time as Jeannot’s captive, Gros reported on a conversation he had with “a mulatto named Aubert.” Aubert explained to Gros the composition of Jeannot’s movement and particularly the surprisingly large number of free people of color it involved. According to Aubert, the movement included “the hardened followers of Ogé,” a free man of color who was executed the previous year for inciting a rebellion.[9] The movement also included “the less daring mulattoes, who, not caring to be exposed, silently and cheerfully awaited the effects of a revolution which they imagined favorable to them” as well as some who were more or less forced to join.[10] Furthermore, in Gros’s short description, we encounter both Black and brown officers as well as a contingent of white priests who perform religious services. One of the leaders of the free men of color was Candi who, having initially fought against Jeannot with his group of militiamen, decided to join Jeannot’s movement. Two weeks after Jeannot’s execution, Candi and his men defected to the royal army.

We can thus speculate, with some confidence, that Jeannot was in fact leading a multi-colored movement. That his vision for general emancipation and presumably better opportunities for free people of color as well was able to unite two groups otherwise opposed to one another. Jeannot was strong in a region in which the free-colored movement against the regime was traditionally strong, and it seems he managed to create a revolutionary ideology and strategy that could unite Black and colored revolutionaries. With Jeannot gone, this alliance no longer held up, and Candi and his men abandoned the revolutionary movement.

Reassessing the Legacy of Jeannot and the Early Revolution

Jeannot’s portrayal as a sadistic figure has overshadowed his significant contributions to the early revolution. His vision of general liberty, independence, and alliances beyond the color line was a precursor to principles that, even if they had their ups and downs, ultimately defined the Haitian Revolution. While Jean-François and Biassou’s reformist approach can be seen as pragmatic, there is also a case to be made that they ultimately set back the revolution and obstructed the fight for emancipation. Jeannot’s strategy represented a more bold and comprehensive vision for freedom, one which was necessarily more utopian than what Jean-François and Biassou imagined was attainably. The limited strategy also failed, and the Black rebels secured freedom only after defeating the colonial powers and obtaining independence.

Whatever the case, the story of Jeannot and his execution highlights the internal divisions and competing strategies amongst the first wave of Haitian revolutionaries. It also underscores the challenges faced by revolutionary movements in balancing pragmatism with radical ideals. By revisiting Jeannot’s role in the revolution, we gain a deeper understanding of the early struggles for freedom in Haiti and the complex dynamics that shaped one of history’s most significant events.

Nicolai von Eggers is an associate professor in history at the University of Aarhus, Denmark. His work on the intellectual histories of the French and Haitian Revolutions has appeared in journals such as Global Intellectual History, History of European Ideas, and the Journal of Caribbean History. He is currently leading a research project on international republicanism in the years 1815 to 1840.

Further Reading:

Nicolai von Eggers, “Why Was Jeannot Executed? A Possible Plan for General Liberty, Independence, and a Black-coloured Alliance at the Beginning of the Haitian Revolution,” Journal of Caribbean History Vol. 58, No. 1 (2024): 1-27.

Jeremy Popkin, Facing Racial Revolution. University of Chicago Press, 2007.

Laurent Dubois, Avengers of the New World. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004.

Marlene Daut, Awakening the Ashes. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2023.

John Garrigus, “Vincent Ogé ‘jeune’ (1757-91): Social Class and Free Colored Mobilization on the Eve of the Haitian Revolution,” The Americas Vol. 68, No. 1 (2011): 33-63.

Endnotes:

[1] Yves Benot argues that revolutionaries fought for independence from the earliest stages of the revolt. See Benot “The Insurgents of 1791, Their Leaders, and the Concept of Independence” in David Geggus and Norman Fiering, eds., The World of the Haitian Revolution (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019), 99–110. David Geggus also suggests that this may have been the case. See Geggus The Haitian Revolution: A Documentary History (Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett), 82. However, John Garrigus, Laurent Dubois, and Malick Ghachem suggest that the struggle for independence only emerged much later as the revolution progressed. See Dubois and Garrigus, eds. Slave Revolution in the Caribbean 1789-1804: A Brief History with Documents (Boston/New York: Bedford, 2006); Ghachem, The Old Regime and the Haitian Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 277.

[2] See for instance C.L.R. James, The Black Jacobins (London: Penguin, [1938] 2001), 77; Carolyn Fick, The Making of Haiti: The Saint-Domingue Revolution from Below (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1990), 113; Laurent Dubois, Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005), 123; Jeremy Popkin, A Concise History of the Haitian Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 42.

[3] Gabriel Le Gros, quoted in Geggus in The Haitian Revolution, 85.

[4] Dubois, Avengers, 115.

[5] Geggus, The Haitian Revolution, 82.

[6] Antoine Dalmas, Histoire de la révolution de Saint-Domingue, vol. 1 (Paris: Mame frères, 1814), 216.

[7] Quoted in Jacques Thibau, Le temps de Saint-Domingue, 302.

[8] Jean-François, Biassou, and Belair Letter (1792) translated and printed in Madison Smartt Bell, Toussaint Louverture: A Biography (New York: Pantheon, 2007), 39-41.

[9] See John Garrigus, “Vincent Ogé ‘jeune’ (1757-91): Social Class and Free Colored Mobilization on the Eve of the Haitian Revolution,” The Americas vol. 68, no. 1 (2011): 33-63.

[10] Aubert quoted in Gros, translated and printed in Popkin, Facing Racial Revolution, 127.