This post is a part of the 2023 Selected Papers of the Consortium on the Revolutionary Era, which were edited and compiled by members of the CRE’s board alongside editors at Age of Revolutions.

By Corinne Gressang

Susan Conner’s work and mentorship have had a profound and enduring impact on French History. In remembering her work, this paper will apply her methodology and findings on prostitutes during French Revolution to the experience of religious women. Two of Conner’s articles will foreground my paper. “Public Virtue and Public Women: Prostitution in Revolutionary Paris, 1793-1794,” which first appeared in the journal Eighteenth-Century Studies, in 1994, and “Politics, Prostitution, and the Pox,” from the 2001 edition of the Journal of Social History contributed enormously to historians’ understanding of the place of women during the revolutionary decade. Susan Connor’s evaluation of the meaning of “virtue” for prostitutes during the French Revolution had resonance for the religious women who also did not fit into the Revolution’s vision for virtuous womanhood. As Conner noted, the “revolutionaries were quick to invoke [Virtue’s] name,” but less quick to grapple with its meaning.[1] Virtue became “republican virtue” and the Catholic Church’s monopoly on virtue became anathema to revolutionary France. While Conner’s work studied the women whose “sexual appetite” was allegedly endangering both men and society, the nuns’ complete refusal of their sexual appetite, through celibacy, was an equal and opposite threat.

Connor’s work builds on historians like Carol Blum, Joan Landes, and Olwen Hufton. Blum traced this new definition of virtue from the pages of Rousseau to Robespierre in her book Rousseau and the Republic of Virtue. She agreed with Conner that virtue remained somewhat unclearly defined. She wrote that virtue “has been treated as a white space into which other, more meaningful signs were to be inserted.”[2] Rousseau was the philosophe who perhaps spent more time than the others agonizing about the virtuous role of women. However, Connor might disagree with Landes about whether women “enthusiastically responded” when Rousseau “extended an invitation to women to join in the creation of his virtuous republic.”[3] Both nuns and prostitutes were unable to respond to this new domestic model of virtue, which excluded them from the public sphere or their religious cloister. Advocating that mothers should serve as natural nurses and fathers as natural teachers, Rousseau criticized parents who neglected the education of their children and shamefully shipped them off to convents.[4] However, despite this shift, it was important to remember that 14 percent of women “born in the second half of the eighteenth century were permanent spinsters.”[5]

Conner described a masculine form of virtue displayed in the strength of one’s civic devotion. The question remained: what happened to the more feminine form of virtue which identified virtue with celibacy and Christian morality?[6] Moreover, Susan Conner’s “Politics, Prostitution, and the Pox,” asked whether revolutionary governments were “willing to deal with these issues [concerning prostitutes] on moral terms, economic terms, or in a social context.”[7] The very same questions emerged concerning the women at the center of my study, sisters and nuns. The Parisian prostitutes and the former nuns had much in common as they tried to navigate a new relationship between virtue and power.

Virtue, for the nun, meant cultivating her relationship with God and becoming more Christ-like. The entire goal of the cloister was the cultivation of virtue. For nuns, virtue was defined by their rule and centuries of Catholic traditions. This sentiment was perhaps best expressed by Gabriel Gauchat, a Visitandine nun from Langres who kept a diary during the Reign of Terror. In it, she argued, “One thing reassures me infinitely in this singular disposition, it is the distance I have from sin and my constant zeal for the practice of virtue. I practice interior and exterior mortification in all that I can; I give a lot of time to prayer, I avoid all dissipation, I keep an exact enclosure; I make requests on all sides to have masses and communions.”[8] A nun practiced self-denial and discipline which helped guide her on a virtuous path. This definition of virtue was founded on Christian principles and practice.

While nuns sought a life that avoided all dissipation, not all women had the financial resources to avoid turning to prostitution in times of need. Although officially condemned prior to the Revolution, prostitution was commonly practiced by women in times of need. It was one of the only types of labor women could perform for which men paid women more money.[9] While prostitution was never lauded, it was nevertheless practiced widely in Paris. These two groups of women soon found themselves outside of the ideal of republican virtue once the Revolution broke out.

When Maximillian Robespierre wrote his famous reports on The Principles of Political Morality on the 18th of Floreal or May 7th, 1794, he was not only discussing the relationship between virtue and terror, but he also outlined a new idea of republican virtue. To women, he wrote;

You will be there, young citizens, to whom victory must soon bring back brothers and lovers worthy of you. You will be there, mothers of families, whose husbands and sons raise trophies to the Republic with the remains of thrones. O French women, cherish freedom purchased at the price of their blood; make use of your empire to extend that of republican virtue! O French women, you are worthy of love and respect from the earth! What have you to envy of the women of Sparta? Like them, you have given birth to heroes; like them, you devoted them, with a sublime abandonment, to the Fatherland.”[10]

The republican ideal for women was to give birth to (and raise) French citizens. Connor argued, “in keeping with this virtue of antiquity, the Jacobins heralded the monogamous marriage, maternity, domesticity, and an ordered society that accepted distinctions between the sexes as a natural, unchanging phenomenon.”[11] However, neither nuns nor prostitutes resembled anything close to this Jacobin vision of virtue.

As France was transforming during the Revolution, women who did not fit neatly into these newly defined roles were often left in vulnerable positions. Conner eloquently argued that women in poverty during the Revolution, “could find no place within this new revolutionary society.”[12] The same could be said for the sisters and nuns who were forced from their religious habits. This raises the question of whether any women found a space in this new revolutionary society that excluded women from politics but required them to perform public duties. As women were increasingly excluded from politics and the public sphere, their role became even more connected to the domestic realm. Both women practicing prostitution and religious observances were a threat to this society.

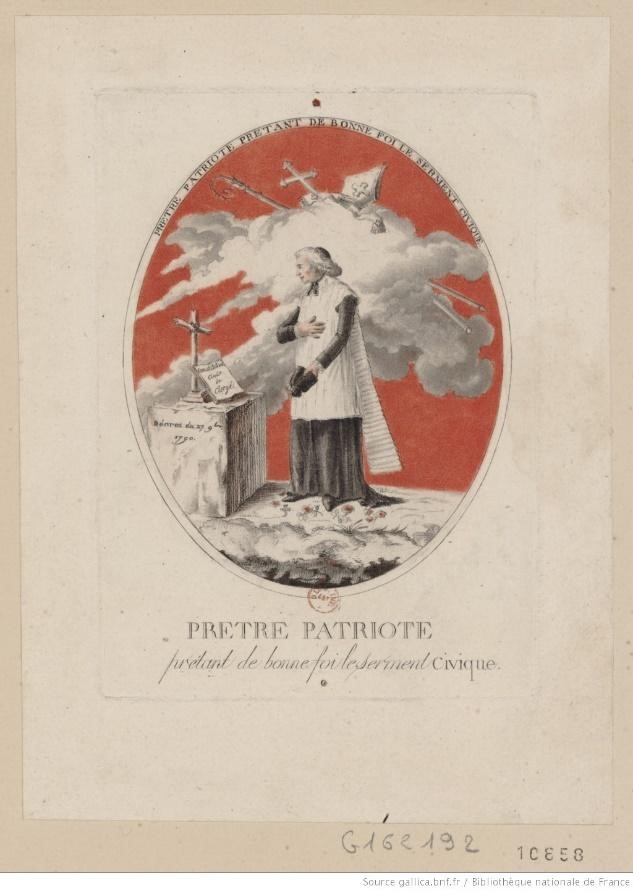

For example, Conner described the legal status of prostitutes as “functionally outside the law,” neither protected nor permitted.[13] The same could be said for women religious. Just a year before as the Code of 19-22 July 1791 redefined the definitions and penalties for municipal offenses like prostitution, a new definition of the role of the Catholic Church in France was already defined in the Civil Constitution of the Clergy (passed in July of 1790). Interestingly, while there was a path for male clergy to be elected to the posts, women religious were conspicuously absent from this new revolutionary religious arrangement. Or, put another way, there was no such thing as a “Constitutional nun,” in the same way as there was a space created for “Constitutional clergy.” The revolutionaries imagined such a thing as a “Patriot Priest”, but could there be such a thing as a “Patriot Nun”? I would argue, their answer would be no. Women’s utility to France lay in her unique childbearing abilities. Nuns who intentionally denied their procreative capabilities were rejecting their very nature and more importantly their unique duties to France.

Meanwhile, the state replaced the church as the arbiter of virtue. While not exactly illegal yet, there are parallels between these two groups of women who were neither protected nor permitted. While patriotism meant performing a useful function for France and virtue meant harnessing each woman’s reproductive potential for the good of France, neither nuns nor prostitutes could easily fit the mold. We could easily sort Conner’s prostitutes and the nuns into the familiar tropes of women as either a seductress or virgin, an Eve or Mary. As many before me have discovered, there was more to compare than to contrast about these two groups of women in Revolutionary France.

Furthermore, for both the prostitute and the nun, Revolutionary agents violated their privacy and intervened in new ways during the years of the Revolution. For the prostitute, this meant venereal disease inspections starting in 1793, and the end of looking the other way when women engaged in this activity.[14] For the nun, it meant their end of a cloistered existence, sealed off from the world. In the D XIX series in the Archives Nationales, agents visited every convent in France to record the people and possessions inside of it. Their houses, possessions, and innermost sanctuaries were searched and prodded. Moreover, representatives penetrated the convent walls to make sure that all the inhabitants had been aware of the prohibition on solemn religious vows (February 13, 1790) and their ability to leave the convent if they chose. For many women, these incursions into their holy sanctuary made them feel a sense of rupture and violence from being ripped from their convents. Under the guise of liberty and revolutionary principles, the revolutionaries violated these women’s privacy. Once again, Gauchat wrote, “Everything in me announced the violence of an all-too-human attachment [to the convent], and the rupture of which threw disorder and anguish into all my faculties.”[15] These new laws, intended to bring freedom, often did not feel like it to the nuns that were affected by them. Another Visitandine, a Mother superior from Lyon, said “death would be a thousand times sweeter to us than a departure from our blessed cloister.”[16] Firmly cloistered nuns were prohibited from having any interaction with the outside world, but then, were suddenly forced into it by the end of 1792. They were forced into the world that they had renounced. Meanwhile, the women who had been engaging in prostitution were also suddenly under much more scrutiny. The nuns’ seclusion from the public was as abhorrent as the prostitutes whose trade was attacked for being too publicly practiced. They represented two aberrations of the revolutionaries’ vision of virtuous women in Revolutionary France.

Another obvious parallel between Conner’s research and my own was the fact that both the convent and the brothel were “practical solutions for economic problems.”[17] First, convents often served as a dumping ground for excess daughters. Families concentrated their wealth to provide for their most eligible daughters. Subsequent daughters were often given lesser dowries to provide for them in the convent. These daughters were often declared legally dead, and therefore, could not lay claim to further inheritances. For families hoping to maintain their wealth or social standing, the convent was a respectable alternative to marriage. To help illustrate the havoc these new inheritance laws played on members of religious organizations, we can look to Margueritte Sophie Badeau, aged forty-two, a professed member of the Visitandine convent in the diocese of Autun. She wrote to the Papal Legate after the Concordat of 1801 to:

take a domain that produces about seven hundred francs in rent, which by right of morte main returned to the power of the lord of the place, when she entered religion… and that since the dissolution of the religious houses, the so-called Margueritte Sophie Badeau has not been able to subsist on any other resource than the modest pension of fifty francs, and the fees which she earned from the education of some young girls. It has been five months since a serious illness made it impossible for her to instruct the children, and because of that enforced rest, she is now reduced to the help of charitable souls. Legal experts consulted believe that according to the current laws of France, Margueritte Sophie Badeau can take possession of her property. [18]

When the revolutionaries changed the laws regarding inheritance and the cloister, there were suddenly new heirs presenting themselves to share in an inheritance that could never have been theirs before the Revolution. This unanticipated flood of possible inheritors was only complicated by the Catholic Church’s restrictions on inheritance for women who had sworn permanent vows of poverty. Legal battles ensued in the decades following the Revolution as these new laws rippled to future generations. These laws had an enormous impact on the economic situation of families.

Similarly, prostitution was a means of survival for women living constantly on the edges of poverty. They were often temporary or seasonal practitioners of the trade.[19] At a time when the Revolution had little funds to spare and was particularly reluctant to help poor women, this was one of their few sources of financial relief. One estimate put prostitution as the largest form of employment for women after the Code of 1791.[20] Meanwhile, convents, a traditional source for charity were closing, mendacity was suppressed, and there were increasingly fewer other options for the estimated 30% of women living in “indigence.”[21] The government would only offer aid to the deserving poor, or those women who could prove dire straits, defined by Conner as a woman with “four, five, or six children, who has been working in textiles or lace… and needs immediate assistance.”[22] Young, single, and able-bodied women need not apply for aid because none would come. These women often had few other choices.

One of the most obvious parallels between Conner’s chosen subjects and my own was the lengths to which the revolutionary laws sought to control and direct female sexuality. A virtuous wife and a mother used her body and allowed her body to be used correctly—through the natural process of marriage, sex, childbearing, and childrearing. Any deviation from this role was a subversive perversion of a woman’s natural state, and therefore, became a threat to the state. I will argue that the nuns’ celibacy was as much, if not more, of a threat to public virtue than the occasional prostitute. During the height of the Revolution, that is the Year II, there was a swift but severe backlash against the visibility of prostitution.[23] October 1, 1793, there was a raid on the prostitutes, inspired by a decree the commune made three days earlier, in it, they argued that prostitutes had disrupted public order and “encouraged libertinage.”[24] Conner did now draw the reader’s attention to the fact that the prostitutes were arrested, but she emphasized how few of them faced the severest penalties for the offenses. While “public women” may not have fit with the new ideals of republican virtue, one in which mores surrounding sexuality were suddenly loosed from the grasp of the church, there was little enthusiasm for punishing practitioners. The revolutionaries preferred women who bore French citizens and raised them in patriarchal families but perhaps recognized the socio-economic need for prostitution.

The nuns were, in some ways, worse. One of the most significant criticisms of nuns in the Enlightenment salons was their unnatural existence outside of marriage. Celibacy was criticized as contrary to nature and cruel. As historian Mita Choudhury has written, “Men of letters began to understand the moral woman as the more natural woman devoted to being a wife and mother.” This meant that “all nuns appeared as deviant women unable to fulfill their natural vocation as wives and mothers.”[25] Their celibacy was, therefore, an unnatural suppression of healthy urges. However, despite the Enlightenment philosophes raging about the dangers of the convent and the revolutionaries’ concerns about the damage that prostitution left on public morals, when it came time to punish these rule breakers, there was little enthusiasm for it.[26] For example, in my research, I found only a small fraction of the 25,000 to 30,000 nuns in France actually faced death at the guillotine.[27] Those who did lose their lives for their faith were charged with political or counterrevolutionary crimes as well.

Conner found that of all the women who were detained or harassed for crimes related to prostitution, only one bore the “full weight of sanctions.” In this unique instance, the woman was drunkenly yelling “vive le Roi, vive le Reine,” a deeply troubling counterrevolutionary sentiment.[28] One might argue that her punishment might have had much less to do with her profession than the Revolutionary Tribunal making an example of her public disobedience. This question of whether she died for her identity as a “femme public” or her counterrevolutionary rhetoric, might not be possible to disentangle.

The same can be argued concerning those alleged “martyrs of the faith” who perished. While the church honors the nuns who died with the title of martyr, the state saw them as simple criminals and counterrevolutionaries. For the church to bestow the title of martyr, the victims had to suffer for their faith. Otherwise, they might be categorized like any other criminal. However, it was undoubtedly true that the nuns who went to the guillotine had broken laws, and many had evidence of counterrevolutionary attachments. For example, the Sixteen Carmelites of Compiègne— who were guillotined and later became the subjects of a novel, a play, and an opera— were officially charged with conspiring against the Republic. Marie de l’Incarnation, a member of the convent who escaped death, reported that the officials “accused them of holding nocturnal meetings, of being in correspondence with the emigrants, including the famous sectarian Théot, who called herself the mother of God; and of having concealed the mantles of the crown.”[29] Of these specific accusations, we can be sure that nearly all of them were true, with perhaps the exception of the accusation about Théot. The Carmelites certainly met in the night to say the divine office. We know they were in correspondence with émigré priests, and we also know they had a close connection to the crown because of their close relationship with Louis XV’s daughter, Marie Louise. Therefore, much like the prostitute who lost her life, the Carmelites did not fit into the vision of republican virtue, but that did not mean that they were guillotined for it. In fact, it was their combination of counterrevolutionary sentiment with public disobedience to the new revolutionary decrees that threatened the Revolution.

Neither the public women nor the former inhabitants of convents truly fit into the new vision of virtue proposed by Rousseau and adopted by Robespierre. Instead, they occupied a sort of in-between space—neither protected nor permitted. Conner’s body of work offers historians the ability to take women on their own terms. In a world where women had limited agency, both nuns and prostitutes made the most of the available options. Susan Conner’s work on prostitution during the Revolution has echoes into the new directions the history of women during the Revolution is taking.[30] As historians, we stand on the analysis of those who came before. I have appreciated the chance to revisit Susan Conner’s work and apply it to my own.

Dr. Corinne Gressang is an Assistant Professor of History at Slippery Rock University. Her dissertation topic developed after reading an editorial in a short-lived Catholic newspaper called L’Ange Gabriel (1799). The editor argued that the French nuns had suffered expulsion from their convents, and they were the most unfortunate victims of the Revolutionary decade. Dr. Gressang’s curiosity about what became of these women became the focus of her dissertation which she is currently revising for publication.

Title Image: Brothel Scene. French School, 18th century, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Endnotes:

[1] Susan P. Conner, “Public Virtue and Public Women: Prostitution in Revolutionary Paris 1793-1794” in Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 28, no. 2 (1994-95), 222.

[2] Carol Blum, Rousseau and the Republic of Virtue: The Language of Politics in the French Revolution (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1986), 30.

[3] Joan B. Landes, Women in the Public Sphere in the Age of the French Revolution (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1988), 66-67.

[4] Rousseau, Emile, 16.

[5] Olwen Hufton, Women and the Limits of Citizenship (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992), 67.

[6] The term virtue was more prevalent in the language of the revolution; however, the issue of morality was a thorny one. The Revolutionaries would have to wrestle with whether there was a moral system that existed outside of Christianity. This topic however is outside of the narrow vision for this paper to compare Conner’s scholarship and its applicability to religious women.

[7] Susan P. Conner, “Politics, Prostitution, and the Pox in Revolutionary Paris,” in the Journal of Social History, (2001), 715.

[8] « Une chose me rassure infiniment dans cette singulière disposition, c’est l’éloignement que j’ai du péché et mon zèle constant pour la pratique de la vertu. Je m’exerce à la mortification intérieure et extérieure en tout ce que je puis ; je donne beaucoup de temps la prière, j’évite toute dissipation, je garde une exacte clôture ; je présente des requêtes de tous les côtés pour avoir des messes et des communions. » Gabriel Gauchat, Journal d’une visitandine pendant la Terreur ou Mémoires de la soeur Gabrielle Gauchat [Reproduction](Paris, 1855), 53. Accessed by http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb37261342x.

[9] Conner, “Public Virtue and Public Women,” 222.

[10] « Vous y serez, jeunes citoyennes, à qui la victoire doit ramener bientôt des frères et des amans dignes de vous. Vous y serez, mères de famille, dont les époux et les fils élève insipides trophées à la République avec les débris des trônes. O femmes françaises, chérissez la liberté achetée au prix de leur sang ; servez-vous de votre empire pour étendre celui de la vertu républicaine ! ô femmes françaises, vous êtes dignes de l’amour et du respect de la terre ! qu’avez-vous à envier aux femmes de Sparte ? Comme elles, vous avez donné le jour à des héros ; comme elles, vous les avez dévoués, avec un abandon sublime, à la Patrie. » Robespierre, The Principles of Political Morality.

[11] Conner, “Public Virtue and Public Women,” 235.

[12] Conner, “Public Virtue and Public Women,” 229.

[13] Conner, “Politics, Prostitution and the Pox in Revolutionary Paris,” 721.

[14] Conner, “Public Virtue and Public Women,” 224.

[15] « Il était sans doute impossible de jeter sur l’état de mon âme un regard juste. Mon extérieur ne dénotait que faiblesse, que tristesse et ennui. Tout annonçait dans moi la violence d’un attachement trop humain et dont la rupture jetait le désordre· et l’angoisse dans toutes mes· facultés. Cependant il n’était rien de moins analogue à mes intimes dispositions. » Gauchat, Journal, 88.

[16] Mère Marie-Jéronyme Vérot, “The Letter,” in I Leave You My Heart: A Visitandine Chronicle of the French Revolution, Mère Marie-Jeronyme Vérot’s Letter of 15 May 1794 Translated and Edited by Péronne-Marie Thibert (Philadelphia: Saint Joseph University Press, 2000), 47.

[17] Conner, “Public Virtue and Public Women,” 222.

[18] Archives Nationales, AF IV 1900, Dossier 1, Piece 24. « Vous Expose Margueritte Sophie Badeau âgée de quarante-deux ans, religieuse professe du monastère de la Visitation Ste. Marie de Charolles au diocèse d’Autun quêtant dans le monde elle prendrait un domaine d’environ Sept cents francs de rente, qui par droit de main morte est rentre au pouvoir de seigneur de lieu, lorsqu’elle entra été religion. Celui-ci outre une dote consistent en un contrat de deux cent vingt-cinq livres de rente, assura à sa communauté un pension ingère de cinquante franca de contrat de deux cent vingt-cinq livres, comme bien ecclésiastique, est entre le mains du Gouvernement français ; de dote que depuis la dissolution des maisons religieuses la dite Margueritte Sophie Badeau n’a en peu subsister d’autre ressource que la modique pension de cinquante francs, et les honoraires quelle retirait de l’éducation de quelques jeunes filles. Il y a cinq mois qu’une maladie grave la met dans l’impossibilité d’instruire les enfants et le tranquille en sort qu’elle est maintenant réduite aux secours des âmes charitables. Des juristes consultes habiles croient que d’après les loix [sic] actuelles de la France, la dite Margueritte Sophie Badeau peut rentrer dans son bien. »

[19] Conner, Public Virtue and Public Women, 222.

[20] Conner, Public Virtue and Public Women, 228.

[21] Conner, Public Virtue and Public Women, 228.

[22] Conner, Public Virtue and Public Women, 229.

[23] Conner, Public Virtue and Public Women, 230. Interestingly, Conner suggests that this is one argument that could be made but hesitates about whether she desires to make it.

[24] Conner, Public Virtue and Public Women, 231.

[25] Choudhury, Convents and Nuns, 5, 6.

[26] Perhaps no work better demonstrates the criticisms of the convent more so than Diderot’s The Nun. Denis Diderot, Leonard Tancock, trans., The Nun, (Penguin: New York, 1974).

[27] Generously calculated, the number of nuns who were put to death for their beliefs was a few hundred. A fraction of the 30,000 who had lived in France. However, the high profile of the Carmelites of Compiègne, who were recently tapped as candidates for equipollent canonization, sometimes obscured the reality that very few faced severe punishment.

[28] Conner, Public Virtue, and Public Women,” 232.

[29] « Le procès-verbal les accusa de tenir des conciliabules nocturnes, d’être en correspondance avec les émigrés, et avec cette trop fameuse sectaire Théot qui se faisait appeler la mère de Dieu ; d’avoir recelé les manteaux de la couronne. » Marie de l’Incarnation, La Relation du Martyre, Manuscrit I.

[30] Recent scholarships on Prostitutes include many of the same themes Susan Connor’s work discussed. For example, Clyde Plumauzille argued that the revolutionaries were willing to recognize the relationship of prostitutes to society “without fully including them in the new civic community.” Clyde Plumauzille, “Sex as Work: Public Women in Revolutionary Paris” in Life in Revolutionary France, Mette Harder and Jennifer Ngaire Heuer, eds. (London: Bloomsbury, 2020), 199.