By Julia M. Gossard

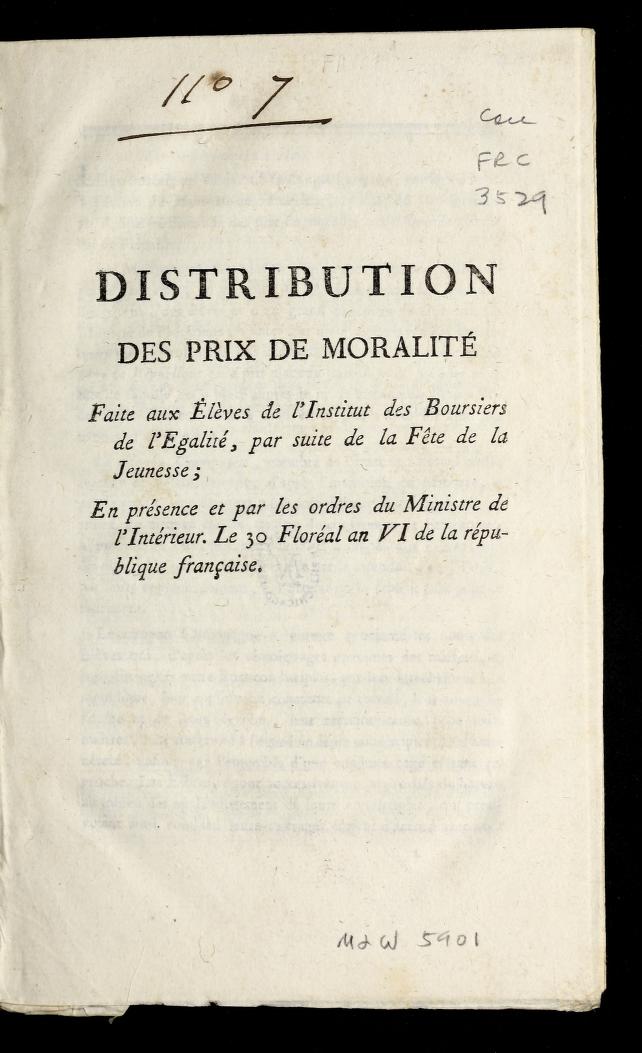

On the 19th of May 1798, Citizen Champagne, the director of the French National Institute of Equality, awarded eighteen students with “morality prizes” (prix de moralité). These prizes recognized students for their outstanding accomplishments in education, as well as their commitments to being ideal, young citizens. Intriguingly, while celebrating the students’ valor, the speech Champagne gave to the crowd during the ceremony acknowledged that the Revolution was in a precarious place. Having come out of the Terror, the Directory was far from stable. There was a palpable anxiety that the achievements the revolutionaries of 1789 fought for would soon be forgotten, replaced with despotism.[1] Using Enlightenment language that emphasized the themes of slavery and oppression, Champagne reminded his pupils that their “fathers received this homeland when she was still degenerate, when she was still enslaved; they set her free.” It was only through “passion, glory, and, of course, fear” that their fathers had overthrown the “master’s yoke.” But within this triumphal narrative, Champagne explained that the Revolution was not over. In fact, it was the students’ “greatest task” to give the next generation “a grander and more illustrious homeland” that would “flourish under [the students] talents, morality, and virtue.”[2]

Champagne was just one of many revolutionaries who imagined that this more progressive French Republic was possible through the intense inculcation of civic morality and virtue in schools. Starting in 1797, a handful of students from their department’s Central School (école centrale) were honored for their dedication to young citizenship at the annual “Festival of Youth” (fête de la jeunesse). In addition to restructuring school curriculum and assignments, incentivizing students with a public award for their educational and civic achievements could help educators more easily mold children into the types of young citizens that were needed in this next unpredictable phase of the Revolution.

Inculcation was not a new method, as the ancien régime had long used charity and local schools in an effort to raise ideal subjects, but the emphasis on civic virtue and morality was a revolutionary invention. Drawing on the Roman republican tradition, the most virtuous of French citizens were those who took an interest in the success of the republic. People had to commit to the ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity. A young citizen’s devotion was to be expressed publicly through unwavering patriotism, reverence for the revolutionaries, strong leadership skills, congeniality with his or her peers, a desire to be a life-long learner by promising to take in interest in the latest political developments and on the continual debate regarding the proper organization of representative government.

At the Youth Festival, the public gathered outside of their department’s école centrale to extol the joys of being a child in a free republic without the shackles of subjecthood and oppression.[3] During the Youth Festival, school administrators gave out a handful of Morality Prizes in grammar, mathematics, physics, and drawing to the most outstanding students in the class. Despite the fact that these subjects do not immediately seem to tie to one’s moral repute, administrators emphasized that every discipline was essential to creating a well-rounded citizen. Speech was essential to communicate with others; art to express oneself; and science to discover the laws of nature. By performing well in their classes, students fulfilled their moral requirement. They were becoming ideal young citizens who could serve their republic well in the future.

To further encourage revolutionary ideals at every level of sociability, students voted in particular categories for their peers. For example, at every institution, one student won the civics prize (prix de civisme). Although school administrators and teachers determined the remaining categories, which included several mathematical prizes, science and physics prizes, art and drawing prizes, as well as grammar prizes, they voted as a faculty in order to avoid nepotism and favoritism. In this way, the prizes became mock elections where students became comfortable with both the practice of voting as well as the rationale behind representative government. This same strategy can be seen around the globe today with students from the United States, Great Britain, and China staging elections for student-run governments and academic clubs. These processes help students learn about civic leadership and the democratic process.

In addition to learning about elections, these prizes encouraged the children of revolutionaries to take up arms in the future and follow in the footsteps of their fathers. With the rise of the Enlightenment and a meritocracy, education became a lynchpin for social advancement for members of the middle and upper classes.[4] Children from notaries, lawyers, professional politicians, and commercial magnates primarily received morality prizes. These schools awarded the prizes as a way to ensure that the direct descendants of the Revolution would shape the future the way the revolutionaries had planned. Starting in youth, one’s popularity and social status depended upon an individual’s commitment to liberty, equality, and fraternity. Youths would internalize this and practice it throughout their lives, according to school administrators.

After the awards were handed out, school administrators usually gave a speech about the importance of patriotism and liberty. Administrators used this as an opportunity not only to further inculcate students but also as an opportunity to reach the larger public. For example, at the École Centrale de l’Eure in 1799, the administrators decided to follow the awards presentation with a tree planting-ceremony they dubbed “The Tree of Liberty.” It adorned the entrance to the school as a “symbol of strength and courage” against the “horrors of oppression.” Much like how a tree had to be nurtured in order to grow, so did young citizen’s sense of patriotism and virtue. But once they had blossomed, both the citizen and the tree would be “glorious examples of the blessed republic.” The administrator ended the speech to a chant of “Vive la République,” which according to the scribe, was shouted for twenty minutes. This ceremony reminded students, their families, and the community-at-large that citizenship and patriotism had to be continually cultivated, like a tree, from infancy to old age.[5]

Although extant documents reveal that only a handful of morality prize ceremonies took place between 1797 and 1799, their existence is still noteworthy. They occurred at a time when the Revolution seemed anything but certain. Patriotism and a belief in the power of liberty waned in the wake of Robespierre’s Great Terror. Republicans were concerned with not making the “same mistakes as Athens,” and having the revolution die out over the next generation. Instead, inculcation in primary and secondary schools would ensure that republicans’ sons, daughters, grandsons, and granddaughters would hold their same Enlightenment values in high regard. But, the prix de moralité may have meant nothing more to the students than serving as little baubles of patriotism in a slowly unraveling revolution. After all, not even inculcation could stop Napoleon’s advancement and the incredible political instability that would characterize the next forty years of French history. Even though the Empire replaced the Republic, this strategy of inculcation remained at the forefront of social reform programs and political debate throughout the nineteenth century.

Julia M Gossard is an Assistant Professor of History and Distinguished Assistant Professor of Honors Education at Utah State University. During her time as a Short-Term Fellow at the Newberry Library in Chicago, IL she discovered French pamphlets pertaining to prix de moralité. Julia researches the history of childhood and youth in eighteenth-century France. At Utah State University, she teaches courses on comparative Atlantic revolutions, early modern and modern European history, and gender, sexuality, and the family. More about her research and teaching can be found on her website: juliamgossard.com. You can also Tweet her @jmgossard.

Further reading:

The Newberry Library’s French Revolution Collection Pamphlets

Mona Ozouf, Festivals and the French Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991).

Lynn Hunt, Politics, Culture, and Class in the French Revolution (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2004)

Endnotes:

[1] Considering that 18 months after Champagne gave his speech Napoleon’s coup d’état on November 9, 1799 would reverse the revolution, perhaps this anxiety was warranted.

[2] “Distribution des Prix de Moralité,” FRC 3529, The Newberry Library (Newberry, hereafter).

[3] “Journal de l’Ecole Centrale et de la Société d’Agriculture du Département de l’Aube,” FRC 5.633.1, Newberry. The Directory organized these types of public, national holidays in order to encourage fraternity, patriotic zeal, and social harmony among the masses.

[4] Charity schools and hospital-orphanages continued to serve children of the poor, giving them a rudimentary education in reading, writing, and arithmetic while teaching them craft skills in preparation for labor or apprenticeships.

[5]“Journal de l’Ecole Centrale et de la Société d’Agriculture du Département de l’Aube,” FRC 5.633.1, Newberry.

One thought on “Prix de Moralité: The Inculcation of Young French Citizens”