This post is a part of our “Native American Revolutions” Series.

By Karim M. Tiro

In July 1779, Claude de Lorimier, an officer in the British Army, was traveling with a party of Mohawk warriors dispatched from the Montreal area to raid Patriot villages in New York. En route, they encountered several Oneida warriors allied with the United States. Rather than engage the putative enemy, the British-allied Mohawks turned on the officer and drove him into the woods. While Lorimier hid, the Mohawk and Oneida warriors cordially discussed how they might avoid harming one another. The Oneidas even had the temerity to ask the Mohawks to supply them with a white captive. The Mohawks demurred, but they did agree to fire their weapons upon departing to mask the parley.[1] This meeting was an exercise in what today would be termed “deconfliction.” It was not an isolated episode.

In choosing sides during the American Revolution, the Mohawks and Oneidas and all other Native nations had to weigh their prospects for retaining their territory and autonomy. As neutrality ceased to be an option, their decisions largely became a function of location. Those who lived farther away from Patriot society (or who had already lost their lands and left) chose to act on what appeared to be a last opportunity to arrest settler encroachment. In the case of the six nations of the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) Confederacy, the already-exiled Mohawks joined with the British, as did the western nations: the Senecas, Cayugas, and Onondagas. The Oneidas and Tuscaroras, whose lands were on the front edge of Indian country, could not afford to alienate their non-Native neighbors. They prudently supported the Patriots. The war fractured the unity of the Iroquois peoples.

However, disunity over the Revolution did not entirely dissolve their sense of shared identity or interest. While Natives aligned with each side were committed to military victory, they hoped their fellow Natives might be spared harm. The kind of meeting that Lorimier described was part of a continuum of cooperative acts. Native prisoners had a penchant for escape when other Natives were their keepers. Native diplomats on multiple occasions tried to dissuade or delay British or American strikes directed at Native targets. And when persuasion failed, Native guides leading the forces toward those targets sometimes had to lose their sense of direction. British and American officers did have an inkling of what was going on. As one put it, “I doe not think that Indians will doe anything to hunt those of their own Colour, Especially those that are Related and connected together as the Six Nations and the Iroquois are…unles there shal happen to be a sufficient number of white people present.”[2]

Of course, deconfliction had its limits. The Revolutionary War was brutal and messy and put Iroquois people in danger at each other’s hands. Without a doubt, the greatest example of such an unwanted encounter was the Battle of Oriskany in August of 1777. While the warriors on both sides did not arrive seeking combat with each other, they did not shy away from it once it started. After several hours of fighting, two hundred British soldiers and Native allies lay dead, including thirty-six Senecas. Casualties on the Patriot side were significantly higher, and included an unknown number of Oneidas and Tuscaroras. Such events could not be allowed to pass with impunity. In retaliation, Mohawks and Oneidas sacked one another’s villages, albeit only after their populations had fled. Significantly, lethal revenge sanctioned by the Native ‘mourning-war’ tradition was generally directed outward, against non-Natives: Senecas clubbed to death Patriot prisoners shortly after the battle. Eleven months later, they again cited their losses at Oriskany when executing more Patriot prisoners.

It is worth noting that, despite the animosity generated at Oriskany, efforts at deconfliction among the Iroquois only increased in its aftermath, and they were successful. The Battle of Saratoga took place only weeks later. According to one participant, the Oneidas and Tuscaroras fought well for the Patriots, but the British-allied Indians “ran off through the wood.”[3] Despite mutual residual resentments, no similar confrontation took place over the six years of war that followed.

During the American Revolution, Native Americans of many nations made very significant contributions—and sacrifices—to both Great Britain and the United States. Indeed, commanders judged their services as scouts, spies, and fighters to be indispensable. In aligning themselves with whichever side offered the best prospect for their independence, Natives gambled on a favorable outcome. Unfortunately, they all lost. Natives who sided with the British saw their ally cede their lands at the peace treaty even though those lands were not theirs to cede. Natives who sided with the Americans never received the gratitude that they thought was their due; they were expropriated just as quickly as the hostile nations. In the war’s wake, the Iroquois were left battered, dispossessed, and divided by an international border. In that context, the history of their covert cooperation was easy to overlook. But we should not overlook it. The American Revolution is sometimes referred to as an “Iroquois civil war,” but efforts at deconfliction show that Natives had not allowed their interests to be completely subsumed by the conflict.[4]

Karim M. Tiro is chair of the Department of History at Xavier University. He is the author of The People of the Standing Stone: The Oneida Nation from the Revolution through the Era of Removal (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011). His current work focuses on the removal of Native American peoples from the northern United States in the 1820s and 30s.

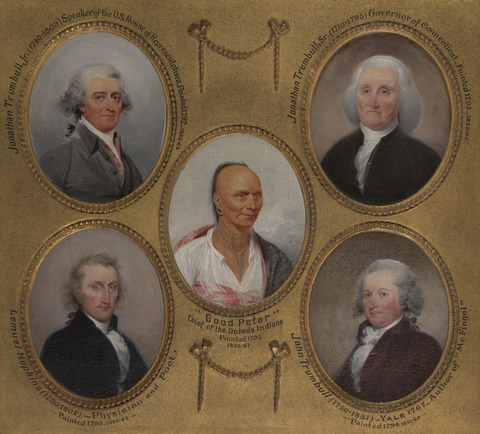

Title image: F. Bartoli, Ki-On-Twog-Ky (also known as Cornplanter ), 1732/40-1836.

Endnotes:

[1] “The particulars of a Conference Held by a Deputation from Mr Lorrimiers Scout with a Party of Oneidas,” July 29, 1779, B120:62-64; Alexander Fraser to Frederick Haldimand, July 29, 1779, B120:56-57, both Haldimand Papers, National Archives of Canada.

[2] Duncan Campbell to Haldimand, July 6, 1780, B111:213, Haldimand Papers.

[3] John Hadcock to Lyman C. Draper, May 6, 1872, Draper Manuscripts, 11U:264, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison.

[4] I investigated this question further in “A ‘Civil’ War? Rethinking Iroquois Participation in the American Revolution” Explorations in Early American Culture 4 (2000): 148-65. For a contrary view, see Joseph T. Glatthaar and James Kirby Martin, Forgotten Allies: The Oneida Indians and the American Revolution (New York: Hill and Wang, 2006), esp. 360n. 21.

Thank you for bringing attention to this critical POV.

Drums Along the Mohawk Outdoor Drama by Walter D . Edmonds in Mohawk, NY includes the Iroquois narrative as a crucial part to the entire story.

drama-drumsalongthemohawk.com

http://www.facebook.com/drumsongthemohawk

Kyle Jenks

Writer,Producer, Director

LikeLike