This post is a part of our “Race and Revolution” series.

By Erica Johnson

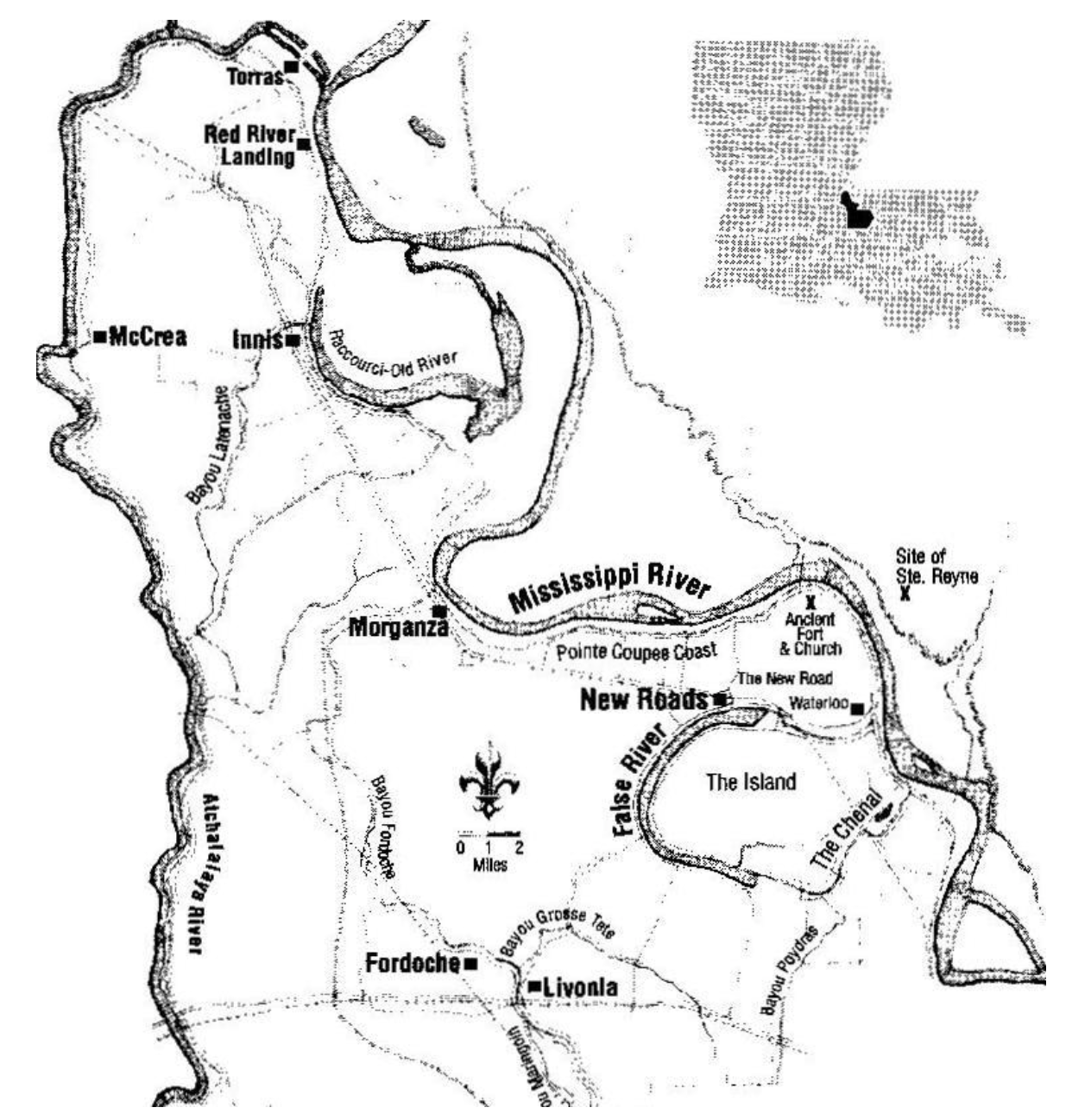

The flight of refugees from the Haitian Revolution intertwined the histories of Louisiana and Saint-Domingue. The story of one refugee, Pierre Benonime Dormenon illustrates how perceptions of the Haitian Revolution and racial prejudices within Louisiana affected an emerging white Creole identity. In Louisiana, Dormenon was the Point Coupée parish judge, but political opposition forces sought his disbarment based on alleged activities in the Caribbean. According to the Louisiana Superior Court Case court report, accusers contended that Dormenon “aided and assisted the negroes in Santo Domingo in their horrible massacres, and other outrages against the whites, in and about the year 1793.” What role Dormenon played in the Haitian Revolution is not clear, nor is it clear how slaves and free people perceived him. Nonetheless, claims of Dormenon’s actions during the Haitian Revolution called into question his own racial identity.

Dormenon’s accusers focused heavily on his racial sympathies. The most shocking portrayal of Dormenon as black was in the testimony of Antoine Remy. Remy recounted a discussion with an innkeeper, a Mr. Prat, in a southern parish of Saint-Domingue. “He [Prat] heard him [Dormenon] say several times that he hated whites and was ashamed to be one of them,” testified Remy. He added, “He [Dormenon] believed that by opening a vein he could take in some black blood.” This testimony is questionable, because Remy based it upon hearsay. However, it was still significant within Dormenon’s case, because it deepened Dormenon’s connection to and sympathy for people of color.

If the prosecution could not make Dormenon black, the prosecution could allege that he took a bride of color, a quadroon woman. According to translator, Henry Paul Nugent, “Remi [sic] and Ellingham [sic] swore in their affidavit that Mr. Dormenon was married, in their presence, to a woman of colour; (which it seems is the same thing as to commit massacres;) in court they declared they had only heard of his marriage.” Dormenon did not arrive in the United States with a wife. He appeared single in all census records, and died a bachelor. He did not even address the supposed marriage in his rebuttal. Despite the lack of evidence, such as a marriage certificate or an eyewitness, the prosecution wanted to emphasize his supposed empathy for people of color.

The accusation of an interracial marriage between Dormenon and a quadroon woman is significant in many ways, especially in regards to the racial prejudice in Louisiana and the intentions of the prosecuting attorneys. The Superior Court tried him for involvement in the massacres in Saint-Domingue; therefore, the union was completely irrelevant. The opposition did not present any solid evidence of a legal union, such as a marriage certificate or firsthand accounts. More significantly, the supposed wedding would have taken place in Saint-Domingue, not in a state or territory of the United States. Saint-Domingue never forbade interracial marriages. The court record did not state if the judge would disbar Dormenon for marrying a woman of color, although miscegenation laws long in effect in Louisiana would have made it plausible.

Louisiana legal history remained consistent on the matter of racial endogamy. The 1724 Code Noir forbade marriages between whites and blacks. The Spanish expanded the regulations to include unions between whites and people of color or mixed concubinage in 1777. Violations of the laws resulted in expulsion from the colony or a fine. Yet, these laws did not prevent biracial unions. There was a brief shift in these laws following the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Oddly, the Black Code of 1806, drafted by the territorial legislature, did not include articles concerning intermarriage. The Digest of the Civil Laws Now in Force in the Territory of Orleans of 1808 prohibited marriages between whites and free people of color in Louisiana.

Dormenon faced disbarment if convicted by the Superior Court of the grave, racialized charges against him. Louisianans could not try him for a crime committed in Saint-Domingue, as they could have while under the French. Trying him for crimes in a United States territory required convincing a jury beyond a shadow of a doubt, and such a conviction would have been unlikely. The Louisiana House of Representatives, a democratically elected branch of the U.S. government, declared Dormenon innocent upon reviewing the evidence of the case. Yet, for a man with a long career in the law, disbarment was not a light sentence. Upon Dormenon’s removal from the bar, Nugent asserted, “The treatment…proves that the bar is in the most abject state of servitude, and that a lawyer may be expelled as arbitrarily as a slave may be sent by his master to jail, to receive a lashing.” This dramatic parallel between a lawyer and a slave certainly expressed Nugent’s perceptions of the misuse of the judiciary by white Creoles within the territory. Dormenon’s white creole identity was under fire, but the fact that the trial took place across empires and beyond borders ultimately protected Dormenon.

Erica Johnson is an Assistant Professor of History at Francis Marion University. She specializes in French Atlantic history. She co-edited The French Revolution and Religion in Global Perspective with Bryan A. Banks. Her book, Philanthropy and Race in Saint-Domingue, is forthcoming with Palgrave MacMillan as part of the Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial series.

Title image: Louisiana, c. 1814

Further Readings:

Nathalie Dessens, From Saint-Domingue to New Orleans: Migration and Influences (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2007).

James Alexander Dun, Dangerous Neighbors: Making the Haitian Revolution in Early America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).

Erica Robin Johnson, Louisiana Identity on Trial: The Superior Court Case of Pierre Benonime Dormenon, 1790-1812. M.A. thesis, University of Texas at Arlington, 2007.

Paul Lachance, “Repercussions of the Haitian Revolution in Louisiana,” in The Impact of the Haitian Revolution in the Atlantic World, David P. Geggus, ed. (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2001), 209-230.

Ashli White, Encountering Revolution: Haiti and the Making of the Early Republic (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010).

Endnotes:

[1] François-Xavier Martin, Orleans Term Reports (St. Paul: West Publishing, 1913), 129.

[2] Testimony of Antoine Remy, in Recueil des dépositions faites pour et contre le Sr. P. Dormenon par-devant la Cour Supérieure du Territoire de la Nouvelle-Orleans, trans. Carol Johnston (New Orleans: Chez A. Daudet, 1809), 11-12.

[3] Henry Paul Nugent, Observations of the Trial of Peter Dormenon, Esquire, Judge of the Parish Court of Point Coupee (New Orleans: Published for the Author, 1809), 107.

[4] Stewart R. King, Blue Coat or Powdered Whig: Free People of Color in Pre-Revolutionary Saint Domingue (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2001), 193.

[5] First Legislature of the Territory of Orleans, “Black Code,” Acts Passed at the First Session of the First Legislature of the Territory of Orleans (New Orleans: Bradford & Anderson, 1807).

[6] A Reprint of the Moreau Lislet’s Copy of A Digest of the Civil Laws Now in Force in the Territory of Orleans (Baton Rouge: Claitor’s Publishing Division, 1971), 24.

[7] Nugent, An Account of the Proceedings, 36.