By Emily Sneff

The New York Times first devoted an entire page to the Declaration of Independence exactly 100 years ago, on July 4, 1918. Thirty years ago, NPR’s Morning Edition began a tradition of reading the Declaration on air. Last year, NPR also published the text in 113 consecutive tweets, and the sheer number of tweets as well as the fragmentation caused by the 140-character limit sparked confusion and criticism.[1] Taken out of context, essential phrases in the Declaration were perceived as subtweets, propaganda, or a call for revolution in the Trump era.

The tradition of publishing the Declaration annually on July 4 dates much further back, however. In fact, it appears that the first printer to republish the Declaration of Independence on July 4 with the intention of marking the anniversary was also the first printer ever to publish the Declaration: John Dunlap. He and David C. Claypoole included the text on the front page of The Pennsylvania Packet, and Daily Advertiser (Philadelphia, PA) on July 4, 1786, the tenth anniversary. By 1801, republishing the Declaration of Independence in newspapers on or around July 4 was a trend on the verge of becoming a tradition and an expectation. The Telegraphe and Daily Advertiser (Baltimore, MD), for example, first included the Declaration by request on July 4, 1799, and republished the text annually through 1806.[2] Before 1801, only a handful of newspapers printed the Declaration in any given year. In 1801, at least twelve newspapers printed the text in late June or early July; by 1806, that number more than doubled. As the individual who requested that the Telegraphe print the Declaration in 1799 wrote to the printer, “you have it in your power to gratify all without displeasing any, by giving it a place…” But, as last year’s tweets proved, even a text as intrinsic to our national identity as the Declaration can become polarizing. The 1801 uptick in July 4 newspaper printings, for example, coincided with a tense moment of political transition, and crystallized in part because of the association between the new President and the Declaration.

Four months before the 25th anniversary of independence, the presidency transferred to Democratic Republican Thomas Jefferson from Federalist John Adams, the two men who would be memorialized by John Quincy Adams as “the hand that penned that ever memorable Declaration and the voice that sustained it in debate.”[3] By this time, it was widely known that Jefferson was the principal author of the text, and his supporters used this as a selling point. The June 30, 1801 True American (Trenton, NJ) printed the Declaration of Independence and Jefferson’s inaugural address, explaining, “The first, severed the bands by which we were held under foreign subjugation, and announced our independence as a Nation—the measures which produced the latter, burst the chains of domestic usurpations, and established our Freedom as Citizens.” A year later, on July 5, 1802, The True American referred to Jefferson as “our present Political Pilot,” and the Declaration as “the chart by which he steers the vessel of state.” The July 23, 1801 Republican Gazette (Concord, NH) prefaced the Declaration with several pro-Jefferson notes, including, “Herein you may find the cause, why the Royalists, the British Federalists, the old and young Tories, hold such an implacable hatred to Mr. Jefferson, whom they have called a ‘coward,’ because they could never intimidate, nor warp him from his inflexible republican principles.”

While Jefferson was praised for his “republican principles,” John Adams was rebuked for forgetting his revolutionary ideals and accused of being a monarchist, and these traits were attributed to their respective parties. A note preceding the Declaration of Independence in the July 3, 1800 American Citizen and General Advertiser (New York, NY) encapsulates the tension at that time. The printers remarked that the “bold and republican declaration” was written, “by Jefferson, whose genius, talents and republican virtues, justly intitle him to the highest honours—to the most exalted station that his country has to bestow.” They then recommended the Declaration “to the attentive perusal of every citizen who venerates the cause of liberty, and who firmly believes that monarchy is not ‘a stupendous fabric of human wisdom,’” a quote pulled from John Adams’ Defence of the Constitutions of Government.[4]

Partisan bickering around the Declaration of Independence even led to “fake news.” On June 30, 1800, the Federal Gazette (Baltimore, MD) reported, “that the man in whom is centred [sic] the feelings and happiness of the American people, Thomas Jefferson, is no more,” with an account of his death a few days earlier (twenty-five years ahead of his actual death on July 4, 1826). The influential Aurora General Advertiser called the story “A Federal Bore!” and declared it “a fabrication intended to damp the festivity of the 4th of July, and prevent the author of the Declaration of Independence from being the universal toast of the approaching auspicious festival.”[5] Unlike the “fake news” of today, it took days for both the false story and correction to spread, and the Aurora’s assertion about timing seems plausible.

Evidence of polarization can even be found at the local level. On July 2, 1805, The Albany Register prefaced the Declaration of Independence with a note that included this statement: “Let the man who declaims against this invaluable instrument, be spurned by freemen as an enemy to the liberty and independence of his country…” A postscript informed the reader that the city council, “composed almost wholly of federalists,” had determined “that the Declaration of American Independence SHOULD NOT be read on the 4th of July inst.” Remarks in the next issue quoted the Declaration itself as a defense for the need to revisit it annually: “‘a decent respect to the opinion of mankind requires’ it.” Ultimately, in a meeting on the morning of July 4, the council reversed its decision, and “every murmur hushed, and the day was celebrated in a manner highly becoming American Freemen.”[6]

In Adams’ and Jefferson’s presidencies as in Trump’s, the challenge of engaging with the Declaration of Independence is that it is both specific to its time, and evergreen. When one looks beyond “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness,” one finds a roadmap for evaluating whether their government has become “destructive of these Ends,” and how to effect change. Specific grievances—for instance, the ones about immigration—were relevant in 1776 and 1800, and are still relevant in 2018. The Declaration of Independence is the inheritance of every American, regardless of party or status, and it is also the responsibility of every American to know the text. For this reason, at the Declaration Resources Project, we have sought to create scholarly resources to support teaching and learning about the Declaration of Independence. Looking beyond the partisan conflicts, our goal of increased and ongoing engagement with the text builds on the example of those newspaper printers who made republishing the Declaration on July 4 a tradition that continues today.

Emily Sneff (on Twitter @emily_sneff) is the research manager of the Declaration Resources Project at Harvard University, and as of Fall 2018, she will be a doctoral student in history at the College of William & Mary. The principal investigator of the Declaration Resources Project is Danielle Allen (on Twitter @dsallentess), and the project’s mission is to create innovative scholarly resources to support teaching and learning about, and ongoing engagement with, the Declaration of Independence. To learn more, visit declaration.fas.harvard.edu or follow @declarationres on Twitter.

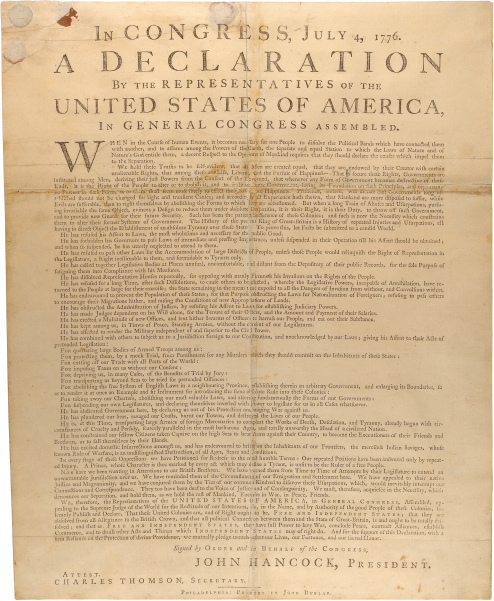

Title Image: The Declaration of Independence in the The Pennsylvania Evening Post, July 6, 1776.

Further Reading:

Allen, Danielle. Our Declaration: A Reading of the Declaration of Independence in Defense of Equality. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2014.

Maier, Pauline. American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. New York: Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., 1997.

McDonald, Robert M.S. “Thomas Jefferson’s Changing Reputation as Author of the Declaration of Independence: The First Fifty Years.” Journal of the Early Republic, 19:2 (Summer, 1999), 169-195. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3124951.

Endnotes:

[1] Amy B. Wang, “Some Trump supporters thought NPR tweeted ‘propaganda.’ It was the Declaration of Independence,” The Washington Post, July 5, 2017 https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2017/07/05/some-trump-supporters-thought-npr-tweeted-propaganda-it-was-the-declaration-of-independence/?utm_term=.6e9a8cd62747

[2] In 1799, John Adams’ name was left off the list of signers, and the error was repeated in 1800. It does not appear to be an intentional slight, but given the timing, it certainly could have been perceived as one by certain readers.

[3] John Quincy Adams, “Second Annual Message,” December 5, 1826. The American Presidency Project, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=29468.

[4] In context, the quote reads, “I only contend that the English constitution is, in theory, both for the adjustment of the balance and the prevention of its vibrations, the most stupendous fabric of human invention; and that the Americans ought to be applauded instead of censured, for imitating it as far as they have done.” John Adams, “A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America,” The Works of John Adams, vol. 4, 1851. http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2102.

[5] As reprinted in the American Citizen and General Advertiser (New York, NY), July 5, 1800.

[6] The Albany Register (Albany, NY), July 9, 1805.

One thought on “Convulsions Within: When Printing the Declaration of Independence Turns Partisan”