By Elena Schneider

You can start a book project thinking it is about one thing, but then realize in the writing that it is actually about another. When—way too many years ago—I began my study of the British invasion and occupation of Havana at the end of the Seven Years’ War, I thought I was writing a story about empires. The book would chart the clash between two competing imperial systems—their similarities and differences, convergences and divides—during a dynamic moment of imperial rivalry and reform. I was writing a book about empires, and I still did to a large extent, but when I immersed myself in the archives, I began to see that the protagonists of this battle were not those that I expected. Written all over eyewitness reports of the fighting in Havana were accounts of the critical role played by free and enslaved people of African descent. Their lives were entangled with empires and in fact shaped them, but they engaged in this battle for their own reasons, and remembered it differently once the cannons fell silent. As I came to see, embedded in this imperial contest over territory was a racial struggle over rights fought by Cuba’s black soldiers. Their struggle became the heart of my book—a story of successes followed by another of broken promises and betrayals.

Over a longer history than just this one battle, foreign machinations against Cuba created opportunities for free people of color who were willing to volunteer as soldiers to protect the island from attack. By putting their lives at risk to defend the island, black soldiers met an urgent need and proved themselves essential to the safety and strength of the Spanish empire. Marginalized in other areas of the economy, they had incentive to volunteer for dangerous military service. Militia service allowed them opportunities to rise by their merits that were not necessarily available in other economic sectors. In response to repeated foreign incursions in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, militias of free people of color cropped up across the island. They were especially large and well established in Havana—the Caribbean’s most populous and wealthiest city, the way station of the fabled Spanish treasure fleets, and the most frequent object of foreign attack.

Because the best defense is a good offense, Havana’s soldiers of color not only defended the island at home but also targeted enemy ships and port cities abroad. Alongside enslaved African laborers, they served on privateering vessels and amphibious operations launched from Spain’s military base in Havana against neighboring British territories. Many of these Spanish operations have fallen off the pages of history books, but they include attacks on the Bahamas (1703, 1720), Pensacola, Florida (1719), Charleston, South Carolina (1706), and St. Simon’s Island, Georgia (1742). In describing these exploits, one of Havana’s earliest chroniclers declared that its population of African descent had a “talent” for war, “proven in expeditions they have made, with credit to the nation and the fatherland.”[1]

Havana’s free population of color leveraged their military service to gain status and privileges in Cuban society. Over generations, free families of color used militia service to help propel themselves into elite status. This phenomenon was not exclusive to Havana, but several historians of Latin America have commented on the ability of soldiers there to ascend social hierarchies. A captain of the militia of free pardos (of mixed race), Antonio Flores provides a striking example. Entering the militia as a common soldier in 1708, he rose through the ranks following his service in several overseas operations in Florida and Georgia, which even saw him taken to France as a prisoner of war. As battalion commander, Flores added the aristocratic prefix “de” to his name and managed to send his sons, later members of the militia as well, to primary and secondary school, despite official exclusions for children of color.[2]

During the British siege of Havana of 1762, Cuba’s black soldiers stood on the front lines of the defense of the Spanish empire from a massive amphibious assault. The attacking British war fleet consisted of more soldiers and sailors than lived in any British American city at the time. In the face of this onslaught, Havana’s defenders included members of the free black militias, already renowned for their military prowess, and more than 3,000 enslaved volunteers who rushed into the city to serve in exchange for their promised freedom. They fought alongside Spanish soldiers and sailors and white militia from the island, but even British combatants commented on the preponderance of men of African descent defending Havana’s Morro fortress and launching counterattacks.

By no means did all people of African descent in western Cuba rush forward to fight for the Spanish crown. Some made a break across enemy lines to spy for the British or fled to the interior to escape their bondage. But in general, blacks in Havana helped make the siege so protracted it almost failed, and British armies lost more men to a virulent yellow fever outbreak than they had in the entire Seven Years’ War in North America. The defense of Havana was so fierce it took down a massive British army and severely limited the plans for the occupation.

After Britain returned Havana to Spain at the end of the war, black veterans of the siege lobbied for greater rights and rewards in recognition for the role they had played in the noble but ill-fated defense. At first their efforts saw some success. The new Captain General sent Captain Antonio de Soledad and his sub-lieutenant Ignacio de Albarado, two officials of the battalion of morenos libres (free blacks) of Havana, to Spain to be honored at the royal court and awarded medals by the King. Other members of the militias of color were singled out for financial rewards and distinctions.

When enslaved veterans petitioned for the manumission that had been promised them during the fighting, a mere 200 of their numbers were set free. Many hundreds more were not. The demands of these men ran at cross-purposes with the labor needs of Cuba’s burgeoning sugar industry. In the wake of Havana’s return, government officials pledged a new commitment to the African slave trade and plantation agriculture in order to renew the economy of the island and build stronger bonds with Havana elites. Crowds of enslaved Africans who had gathered in Havana’s Plaza de Armas in pursuit of their freedom were ordered to go home and return to “subordination under their owners.”[3] Soon the petitions of free black militia members for better treatment would fall on deaf ears as well.

In bitter moments like these—and others would follow—black veterans were forced to come to terms with the full stakes of having fought in wars for an empire that enslaved and oppressed them. These wars offered scarce and precious opportunities to grasp their freedom or improve their lives. But as they learned soon after, the societies they fought for would not hesitate to break promises made to them after their military necessity had passed. This is a familiar history throughout the hemisphere, and it applies to the experiences of black soldiers in wars as diverse as the Spanish-American-Cuban War, World War II, and Vietnam. It also rings true today. Too often veterans return home to find the endemic racism and bias that drove them into military service has not abated, especially if they are immigrants of vulnerable status or people of color. As history has too often shown, when the fighting is over, another battle resumes.

Elena Schneider is an assistant professor of history at the University of California, Berkeley. Her book The Occupation of Havana: War, Trade, and Slavery in the Atlantic World was published by the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture and the University of North Carolina Press in 2018. Her research and teaching focus on Atlantic History, Cuba and the Caribbean, and comparative colonialism and slavery.

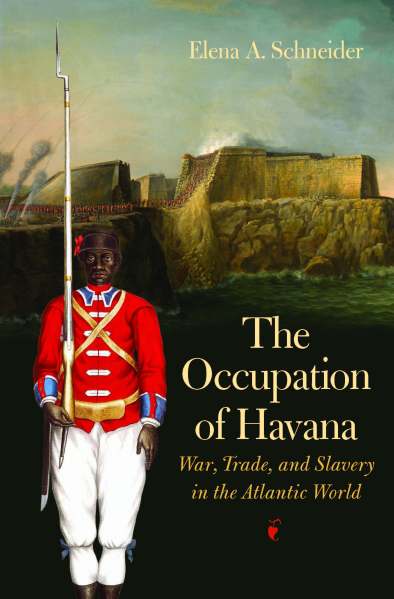

Title image: “Design of the Uniform of the Battalion of Morenos of Havana,” by the mulato painter José Nicolás de la Escalera, Archivo General de Indias.

Endnotes:

[1] José Martín Félix de Arrate, Llave del Nuevo Mundo: Antemural de las Indias Occidentales (Havana, 1964), 97.

[2] On Antonio Flores and his family, see Ann Twinam, Purchasing Whiteness: Pardos, Mulatos, and the Quest for Social Mobility in the Spanish Indies (Stanford, Calif., 2015), 152 –158; Herbert S. Klein, “The Colored Militia of Cuba,” Caribbean Studies, VI, no. 2 (July 1966), 17–27; Pedro Deschamps Chapeaux, Los batallones de pardos y morenos libres (Havana, 1976), 26, 56–60; María del Carmen Barcia, Los ilustres apellidos: Negros en la Habana colonial (Havana, 2009), 355 –356; and Jane Landers, Atlantic Creoles in the Age of Revolutions (Cambridge, Mass., 2010),152 –154, 162.

[3] AGI Santo Domingo 1212, Ricla to Arriaga, Nov. 20, 1763.