By Robin Wright

At the Washington state capitol in Olympia, a man wrapped in an American flag jacket held a home-made sign boldly proclaiming, “Give me liberty or give me COVID 19.” He joined thousands of protestors who came out to denounce stay-at-home orders imposed by state governors. Around the country, cardboard placards asserted protestors’ commitment to “Live free or die.” In Ohio, Michigan, and California, protestors insisted that, “My Constitutional Rights are Essential,” and in Kentucky protestors labeled the governor a “tyrant.” Some even attribute the coronavirus to “King George (Soros),” linking protests to the colonists’ rebellion against King George III, while reinforcing anti-Semitic conspiracies about Jewish philanthropist George Soros. In each case, protestors used the words of the founding fathers to legitimate their anger and appealed to the American Revolution to justify their defiance.

Images of the protests circulated widely, with observers generally deriding the conflation of public health ordinances with rising tyranny. Many were incredulous that someone would invite death via COVID-19 rather than acquiesce to temporary restrictions. With revelations of big-donor money behind some of the protest Facebook pages, it seemed as if these unlikely protests were astroturfed, or falsely made to appear grassroots through the concealed orchestrations of conservative foundations.

Yet the rhetoric and rage displayed in recent protests is not new. Protestors are drawing on a broader conservative discourse centered on the Constitution and American Revolution. Across a diverse cohort of right-wing, libertarian, militia, pro-gun, and white nationalist movements, the Constitution functions as a key symbol in the struggle to advance white exclusionary claims to the U.S. nation. These groups position contemporary grievances as a continuation of the founding fathers’ struggle against tyranny. Speakers at rallies and online commenters herald the coming of the Second American Revolution, inciting patriots to remain armed and ready for combat. Facebook pages are filled with memes referencing a quote by Thomas Jefferson, “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.”

The genealogy of this rhetoric extends back to the reorganization of militia and white nationalist organizations in the 1980s, when white nationalist leaders like Louis Beam believed that a white insurrection was the only way to defend the Constitution.[1] Timothy McVeigh was wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with Jefferson’s quote when he was arrested for the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. Tea Party activists in the early 2000s named the movement after the 1773 Boston Tea Party. Most recently, the occupiers of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge claimed that public lands were unconstitutional and tyrannical.

Recent protests tap into this constitutional talk, equating governors and legislators with tyrants who must be overthrown to protect liberty. Appealing to the American Revolution allows protestors to identify as the “the people” acting in righteous defense of the Constitution. This conflation of COVID-19 protestors with “the people” positions white, suburban Americans as the “true” Americans.

Claiming that only three percent of Americans participated in the American Revolution, contemporary militia groups signal that a virtuous minority can win a war on behalf of the silent majority. They further argue that the Constitution benefitted of all Americans, even though it was written by white men. By comparing themselves to the founding fathers, conservative activists argue that they do not have to be representative of the American public to represent the public’s interests. As true Constitution lovers, they have the moral authority to determine what is best.

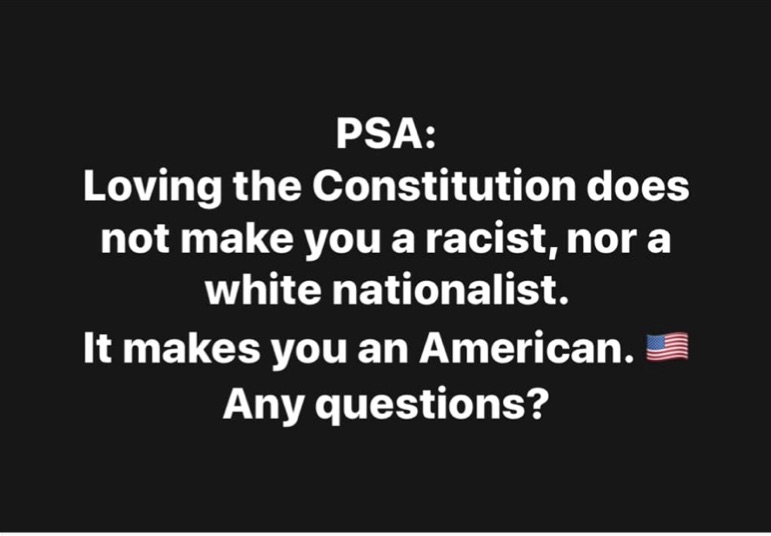

Asserting the moral authority of the founding fathers and contemporary protestors conveniently side-steps questions of race. As one meme proclaims, “Loving the Constitution doesn’t make you a racist, or a white nationalist! It makes you an American.” Constitutionalists argue that race no longer matters because racism no longer exists. A patriot can be any color, so long as you defend the Constitution.

While this appears racially neutral, it naturalizes white privilege by delegitimizing any right to state services or redress based on race and structural racism. A world where race does not matter is a world with no collective accountability, only self-responsibility. It thus renders current demands to protect certain classes of people (by geography, race, ability, etc.) as anti-American, even tyrannical.

The language of tyranny trades a structural analysis of power for a more convenient story of good and evil. Tyrants are the enemy of all, regardless of race, gender, sexuality, or religion. As the supposedly unmarked group, white people become “the people,” able to make group-specific claims under the guise of universality.

The COVID-19 protestors are not all white, but invoking “the people” through revolutionary language protects the structural forces of racial inequality that have marked this nation since its birth. This narrative rejects the foundational role of slavery in America’s formation; the vitriol directed towards the New York Times’ 1619 Project exemplifies the denial of white supremacy in America’s history. Hillsdale College, the conservative beacon of liberal arts education, created a new online course to disprove that “the central feature of America is not freedom, but slavery.”

It also elides the founding fathers’ desire to advance the dispossession of Native land. Occupiers of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge claimed the land as constitutionally theirs and desecrated Paiute artifacts. Yet they also hailed the Burns Paiute Tribe as fellow victims of oppression by the federal government, gesturing to Native presence only to bolster their own position.

“We the people” advances white nationalism by defending white privilege even as it disavows the explicit racism of white supremacist movements. Revolutionary rhetoric not only legitimates exclusionary politics, it primes people to be ever-vigilant against the threat of tyranny. Within this discourse, COVID-19 represents just such a threat. Whether it’s via China, George Soros, or 5G towers, the novel coronavirus appears to be the perfect foil for new attacks on (white) Americans’ unbridled autonomy. While GOP money may play a roll, self-described patriots already attuned to constitutional talk did not need to be told to be mad. They were already scanning the horizon for new infringements on their constitutional rights, with a ready-at-hand framework to justify their actions as the descendants of the founding fathers and standard-bearers of the Constitution. They saw the signs. They had the guns. The second American Revolution was coming, and they were ready.

Robin Wright is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Geography, Environment, and Society at the University of Minnesota. Her dissertation explores right-wing mobilization of the Constitution in the Pacific Northwest, and her research interests include race, law, and social media studies.

Title Image: Photo of 2020 protests to re-open the economy in Olympia, Washington.

Further Reading:

Belew, K. Bring the war home: The white power movement and paramilitary America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018.

Bonds, A., and J. Inwood. “Beyond white privilege: Geographies of white supremacy and settler colonialism,” Progress in Human Geography, 40/6 (2016), 715-33.

Flint, C., ed. Spaces of hate: Geographies of discrimination and intolerance in the U.S.A. New York: Routledge, 2004.

Gallaher, C. On the fault line: Race, class, and the American patriot movement. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003.

Moreton-Robinson, A. The White Possessive: Property, Power, and Indigenous Sovereignty. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

Endnote:

[1] Kathleen Belew, Bring the war home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018).