Click here for part one, which focuses on the legal history of the nègres épaves in colonial Haiti. Part two (click here) examines how two mid-eighteenth-century wars affected colonial Haiti’s response to runaways.

By Erica Johnson Edwards

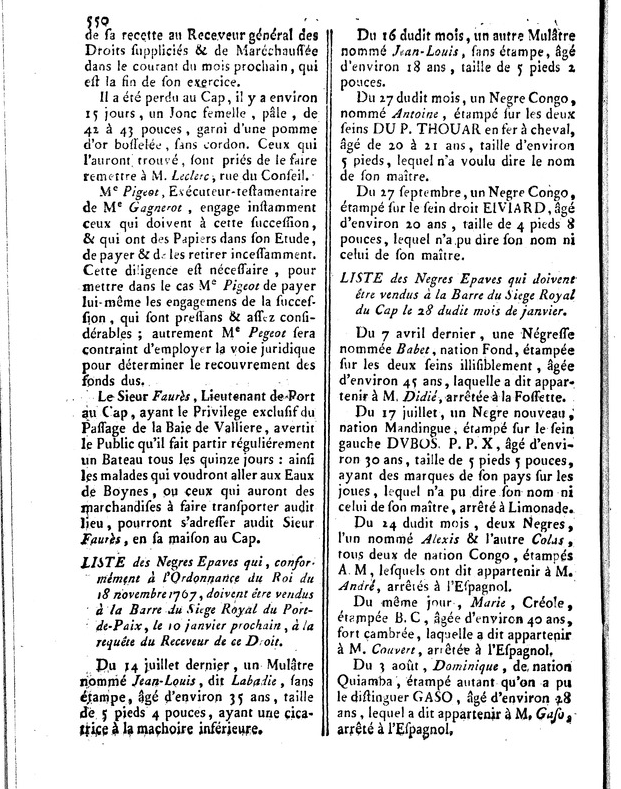

In November 1767, King Louis XV issued a comprehensive set of regulations for nègres épaves in colonial Haiti. Article III of the king’s ordinance required publication of lists of the nègres épaves in the Affiches Américaines before their sale.[1] Despite the inconsistency of the information in the advertisements in the Affiches, it is possible to learn significant details about who the unclaimed runaways were. They were young and old, creole or from scattered parts of West and Central Africa and bore marks of their origins and their enslavement. Colonial authorities and colonists who dehumanized them carried out this process of detaining, advertising, and selling these runaways. A careful review of newspaper records, though, reveals other aspects of the humanity of these men, women, and children who attempted to self-liberate in colonial Haiti in the period between the end of the Seven Years’ War in 1763 and the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution in 1791. I provide a small sampling of the contents of the Affiches in this post.

During the first five years after the king’s ordinance, the Affiches Américaines advertised 372 nègres épaves between ages 4 and 66. However, most of those with a listed age were in their 20s or 30s, but authorities did not provide an age for at least half of those in the Affiches. In Cap Français, the baby of an unnamed 18-year-old woman (Congo) died within 3 days of their imprisonment.[2] The authorities provided this information to indicate that she had been pregnant and recently gave birth to alert a slaveholder or manager who might claim her or to promote her fertility to potential buyers at an auction. Indeed, a woman with a child would be appealing to slaveholders for her fertility, but there was no guarantee they would be sold together. For example, having captured Nannette (Coueda) with her 4-year-old child in Dondon in early August 1773, authorities intended to sell them both in January of 1774.[3] These two cases are striking because women represented less than 15% of reported runaways, most likely because of their parenting roles.[4] Indeed, the majority of maroons were male. The Affiches Américaines advertised 12-year-old Daniel (Congo), 13-year-old Charles (Nago),14-year-old Jean-Jacques (Thiamba), 55-year-olds Jacques (Timbou) and Hardi (Arada), and 66-year-old Jean-Baptiste (Miserable) among the nègres épaves to be sold in colonial Haiti.[5] While Daniel, Charles, and Jean-Jacques were still teenage boys, the advertisement describes how Jean-Baptiste and Hardi presented their advanced age, having white hair and grey beards.

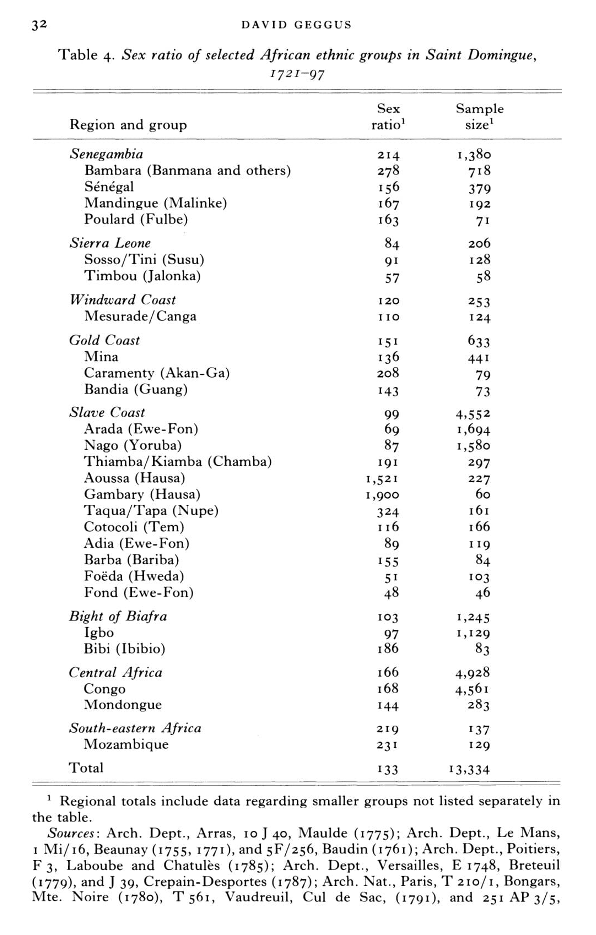

From 1768 to 1773, the Affiches Américaines advertised nègres épaves who were Carib, creole, and African-born. In early September 1771, the Barre du Siège Royal de Saint-Louis listed a Carib runaway named François. Although he was listed as “said to be free,” without proof of his freedom and having been imprisoned for over four months, he was set to be sold on the first of October.[6] Similarly, Jean-Nicolas, a mulâtre creole from Curaçao (a Dutch colony), was listed as “said to be free” among the nègres épaves from Cap in February of 1772.[7] Since the 1767 ordinance did not explicitly address runaways who were “said to be free,” members of the justice system relied upon a law from 1713. The earlier ordinance stated that blacks who claimed to be free but could not prove their freedom would be “declared épaves, acquired and confiscated for sale for the profit of the king.”[8] Further, each list of nègres épaves included runaways of various ethnicities of West Africa. For example, in mid-May 1773, the Barre du Siège Royal du Petit-Goave listed an unnamed Cotocoli (Bight of Benin) man, Pierre and Cupidon as Ibo (Bight of Biafra), and Polite, César, Gaspard, and la Fortune as Congo (West Central Africa).[9]

Whether born in the Caribbean or Africa, the nègres épaves advertised in the Affiches Américaines bore marks of their origins and their enslavement. Descriptions of Jean (Canga) and an unnamed negre nouveau (newly enslaved person) (Congo) included marks of their African ethnicities as well as brands burned onto their skin by their enslavers. The advertisement does not elaborate on the markings from their African homes. However, it does provide the locations on their bodies and identifiable letters of the brands.[10] Though these two men were branded, not all runaways had brands, as was the case with Jean-Nicolas, an unbranded mulâtre creole from Curaçao mentioned above. But brands were not the only markings of enslavement that runaways bore. When authorities arrested François (Congo) in late March of 1770, he was wearing a nabot au pied (ball and chain on the foot).[11] This suggests he had previously made an unsuccessful attempt at maronnage. Further, it is likely some runaways suffered injuries from their violent capture by the militias or maréchaussée. For instance, Louis (Congo) had lash marks on his left shoulder and some of his teeth had been knocked out.[12] In addition, Pierre (Bambara) and François (Caramenty) had scars from smallpox.[13] It is possible Europeans used these enslaved men to experiment with the disease and treatments.[14]

While authorities and colonists used the Affiches Américaines to advertise nègres épaves for sale as chattel, the newspaper listings allow historians a glimpse into the humanity of the diverse peoples sold in this eighteenth-century intracolonial slave trade. Further, it highlights the brutality of enslavement and the real risks of maronnage. Many enslaved peoples in colonial Haiti, whether born in the Americas or Africa, bore brands burned onto their skin by their enslavers to mark them as property. As these advertisements show, age was not a factor in maronnage. Men, women, and children attempted to self-liberate from the horrors of slavery. As the previous two posts showed, nègres épaves were pawns in the struggles for authority fought between colonial and metropolitan authorities. Yet, this post highlights how runaways also engaged in this battle for authority. Instead of fighting over property, they fought for their lives. Prior to the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) that ended slavery in colonial Haiti, enslaved peoples on the island revolted against their enslavement continuously throughout the eighteenth century.

Erica Johnson Edwards is Assistant Professor of History at Francis Marion University. She is the author of Philanthropy and Race in the Haitian Revolution, part of the Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

Title image: Leonard Parkinson, Maroon Leader, Jamaica, 1796.

Further readings:

Manigat, Leslie F. “The Relationship between Marronage and Slave Revolts and Revolution in Saint Domingue-Haiti.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences (June 1977): 420-438.

Debien, Gabriel. “Le Marronage aux Antilles Françaises au XVIIIe siècle.” Caribbean Studies. Vol. 6, No. 3 (Oct. 1996): 3-43.

Eddins, Crystal Nicole Eddins. African Disaspora Collective Action: Rituals, Runaways, and the Haitian Revolution. PhD Diss., Michigan State University, 2017.

Geggus, David. “On the Eve of the Haitian Revolution: Slave Runaways in Saint Domingue in the Year 1790.” Slavery & Abolition Vol. 6, No. 3 (1985): 112-128.

Endnotes:

[1] Louis-Elie Moreau de Saint-Méry, “Ordonnance du Roi concernant les Negres épaves. Du 18 Novembre 1767,” Loix et Constitutions des Colonies Françoises de l’Amérique sous le Vent, vol. 5, (Paris, nd), 139-141.

[2] Etat des Negres Epaves qui, conformément à l’Ordonnance du Roi du 18 Novembre 1767, doivent être vendus le 27 Juillet prochain, à la Barre du Siege Royal du Cap, à la diligence du Receveur de ce Droit,” 22 May 1771, Affiches Américaines, 207.

[3] Coueda was an ethnicity in the Bight of Benin. “Liste des Negres Epaves qui doivent être vendus à la Barre du Siege Royal du Cap le 28 dudit mois de janvier,” 17 November 1773, Affiches Américaines, 551.

[4] Crystal Nicole Eddins, African Diaspora Collective Action: Rituals, Runaways, and the Haitian Revolution, PhD Diss., Michigan State University, 2017, 130.

[5] “Liste des Negres Epaves qui doivent être vendus à la Barre du Siege Royal du Fort-Dauphin, le 1 avril prochain, à la requête du Receveur de ce Droit,” 27 February 1773, Affiches Américaines, 94; “Le lundi 4 du mois de Janvier prochain, il sera vendu à la Barre du Siege Royal de Jacmel, à la requête du Receveur des Epaves audit lieu, conformément à l’Ordonnance du Roi du 18 Novembre 1767, 11 November 1772, Affiches Américaines, 548-549; “Etat des Negres Epaves qui, conformément à l’Ordonnance du Roi du 18 Novembre 1767, doivent être vendus le samedi 7 Juillet prochain, à la diligence du Receveur de ce Droit. Extrait des Registres des prisons Royales du Port-de-Paix,” 16 May 1770, Affiches Américaines, 235; and “Liste des Negres Epaves qui doivent être vendus à la Barre du Siege Royal du Cap le 28 dudit mois de janvier,” 17 November 1773, Affiches Américaines, 551-552.

[6] “Etat des Negres Epaves qui, conformément à l’Ordonnance du Roi du 18 Novembre 1767, doivent être vendus le premier Octobre prochain, à la Barre du Siege Royal de Saint-Louis, à la Requête du Receveur de ce Droit audit lieu,” 4 September 1771, Affiches Américaines, 383.

[7] “Etat des Negres Epaves qui, conformément à l’Ordonnance du Roi du 18 Novembre 1767, doivent être vendus le 28 mars prochain 1772, à la Barre du Siege Royal du Cap, à la Requête du Receveur de ce Droit audit lieu,” 22 February 1772, Affiches Américaines, 95.

[8] Moreau de Saint-Méry, “Ordonnance des Administrateurs, touchant des Negres Epaves; Arrêtés relatifs à son enregistrement au Conseil du Cap, et Arrêtés du Conseil d’Etat portant cassation desdits arrêtés, ect. Des 18 Février, 4 Avril, 21 Juillet et 18 Novembre 1767; 10 Février, 8 Mars, et 6 Juin 1768,” Loix et Constitutions, 94.

[9] “Etat des Negres Epaves qui, conformément à l’Ordonnance du Roi du 18 Novembre 1767, doivent être vendus le 2 Juillet prochain, à la Barre du Siege Royal du Petit-Goave, à la Requête du Receveur de ce Droit audit lieu,” 19 May 1773, Affiches Américaines, 233-234.

[10] “Etat des Negres Epaves qui seront vendus le 5 octobre prochain, à la Barre du Siege Royal de Saint-Marc, à la Requête du Receveur des Epaves,” 26 August 1772, Affiches Américaines, 415-416.

[11] Gabriel Debien suggested that a nabot de pied could weigh around 25 pounds. Se “Les esclaves des plantations Mauger à Saint-Domingue (1763-1802),” Bulletin de la Société d’Histoire de la Guadeloupe, no. 43-44 (1980), 70. “Liste des negres marons que le Receveur des Epaves du Fort-Dauphin se propose de vendre à la Barre du Siege Royal dudit lieu le 5 juillet prochain,” 25 April 1770, 203.

[12] “Etat des Negres Epaves qui, conformément à l’Ordonnance du Roi du 18 Novembre 1767, doivent être vendus le 13 janvier prochain, à la Barre du Siege Royal du Port-au-Prince, à la Requête du Receveur de ce Droit,” 1 December 1773, Affiches Américaines, 571.

[13] “Etat des Negres Epaves qui seront vendus le 3 octobre prochain, à la Barre du Siege Royal du Port-de-Paix, à la Requête du Receveur des Epaves,” 5 August 1772, Affiches Américaines, 380; and “Etat des Negres Epaves qui, conformément à l’Ordonnance du Roi du 18 Novembre 1767, doivent être vendus le 7 Octobre prochain, à la Barre du Siege Royal du Port-au-Prince, à la Requête du Receveur de ce Droit,” 25 August 1773, Affiches Américaines, 404.

[14] See Linda Schiebinger, Secret Cures of Slaves: People, Plants, and Medicine in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2017).