This paper is an outgrowth of a talk given at the Newberry library on January 15, 2021.

By Christine Adams

Many Americans may be tempted to interpret Biden’s inauguration as the opening of a new chapter, and in many ways it is, but we must remain on guard to the extremism that persists in the United States. In the wake of the violent attacks on the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, historians have stepped forward to offer ways to think about these events. Drawing on their own areas of expertise, they have looked to the past as a way of understanding the tensions of this particular moment. Those who cannot remember the past are not condemned to repeat it—pace George Santayana. History does not repeat, and no historical event offers a perfect parallel to the present. As Margaret MacMillan notes, “There are no clear blueprints to be discovered in history that can help us shape the future as we wish. Each historical event is a unique congeries of factors, people, or chronology.” However, she also suggests that “by examining the past, we can get some useful lessons on how to proceed and some warning about what is or is not likely to happen.” In her words, history can help us to be wise. [1]

The unsettled era of the French Revolution (1789–1799) offers insight to our current historical moment as the former U.S. president still refuses to accept recent election results as legitimate, firing up an already potent and dangerous White nationalist movement that feeds on social media-fueled fever dreams. During the tumultuous 1790s, the French grappled with the desire for and fear of change, deep political divisions, profound social inequalities, and rumor and fear-mongering, all against a backdrop of war and economic strain. The violence that emerged from these tensions and France’s inability to arrive at a stable democratic political consensus are reminders that political and social progress are never linear. Particular moments—including the September Massacres of 1792, the Reign of Terror, and Thermidor and its aftermath—offer lessons for our fractured times.

1. Rumor, disinformation, and fears of conspiracy can be profoundly dangerous when they take hold in a society.

When the French Revolution broke out in 1789, it seemed at first that the country would become a constitutional monarchy. However, the French king, Louis XVI, was less than enthusiastic about his loss of authority, and many others—especially members of the nobility and the Catholic Church—opposed the shift to representative government, often working actively to undermine it. The result was that people on the political Left in favor of more democratic institutions and potentially a republican form of government became increasingly radicalized in response to what they saw as resistance from the Right. Consequently, the political scene in France became increasingly tense over the course of 1791 and 1792, with sporadic outbreaks of violence.

Tensions were spurred along by the media. Freedom of the press had been instituted under the reforms of the National Assembly in the early phases of the Revolution, leading to an explosion of newspapers. While some journalists tried to be objective, others simply amplified wild rumors. The Leftwing press frequently expressed frustration with the slow pace of political reform. Their level of trust in the institutions of government was low, and the rhetoric they employed aroused the popular classes against the elite, especially the former nobility. The most radical newspapers—including Jean-Paul Marat’s L’Ami du peuple (Friend of the People) and Jacques-René Hébert’s Père Duchesne, narrated in the voice of a Parisian working class man, a sans-culotte—gave voice to class hatreds. These and other radical newspapers were especially inflammatory in stirring people up against the “aristos,” technically the former nobility, but a term that came to define anyone opposing the Revolution. [2]

Adding to the inflammatory mix, France declared war on Austria and Prussia in the spring of 1792, believing that the two monarchies were a threat to their fledgling constitutional government, especially after the Austrian emperor Leopold II and the Prussian king Frederick William II issued the Pillnitz Declaration in 1791 in support of Louis XVI. It was a toothless document, but one that revolutionaries in the government found threatening. Many French people were convinced that the king and nobility were in league with France’s enemies, the other crowned heads of Europe. This was not entirely wrong; French queen Marie-Antoinette was the sister of Leopold II of Austria, and the aunt of his successor, Francis II. In addition, a significant number of aristocrats and members of the royal family had emigrated as early as the summer of 1789, and were encouraging war on France in support of the Old Regime. By the summer of 1792, it was clear that the war with Austria and Prussia was not going well for the French, and Paris was a powder keg.

As anxiety grew, the people of Paris stormed the Tuileries Palace, home of the royal family, on August 10th, 1792. The constitutional government, the Legislative Assembly, agreed to the demands of the insurrectionary Paris Commune, which controlled Paris, and suspended the king’s authority. This signified the end of the monarchy. The National Convention, which replaced the Legislative Assembly, undertook the task of writing a new constitution; France would become a Republic on September 21, 1792.

Even with the king and his family under arrest, the situation in Paris became increasingly fraught over the course of the month of August. The Duke of Brunswick, leading the Prussian troops, had issued the Brunswick Manifesto on July 25, 1792, which promised severe retribution upon the city of Paris if any harm befell the royal family, a terrifying prospect as the Prussian army moved towards the frontier. However, supporters of the Revolution were more focused on counterrevolutionaries within the country who they believed were in league with émigrés and foreign armies.[3] They intensified efforts to root out traitors, leading to numerous acts of violence and lynchings of suspected conspirators throughout the country during the month of August. The result was that the prisons of Paris rapidly filled with suspects arrested on what were often pretty flimsy grounds. In addition, the Legislative Assembly had already armed volunteers with pikes to defend the city of Paris from the Prussians. As David Bell points out, pikes were not particularly practical for holding off the Prussians—they had not been in serious use in west European warfare for over a century, but they drew on the classical imagery beloved of French politicians. And while not very useful on the battlefield, pikes could be quite effective in massacring fellow citizens.[4]

2. In a context of deep political divisions, widespread disinformation, economic crisis, and social unrest, overheated rhetoric can lead to violence. Groups of individuals who commit these violent acts see themselves as honorable defenders of a cause, not as a violent mob.

On August 31, Parisians learned that the Prussian army had taken the French key fortress of Verdun two days earlier, which meant that the path to Paris lay open. As desperate citizens prepared to defend their nation, Parisians became obsessed with false rumors of aristocrats and priests hatching anti-revolutionary plots in the prisons of Paris. Journalists took the lead in rallying people to action. In L’Ami du peuple, the radical newspaper, Jean-Paul Marat urged his readers to “go to the Abbaye, to seize priests, and especially the officers of the Swiss guards and their accomplices and run a sword through them.” [5] His was one of the most active voices urging on the massacres about to take place. He paid a price for it—the following year, Charlotte Corday, a young woman from Normandy, would travel to Paris and murder him in his bathtub, in large part because of his role in the massacres.

But it was not only journalists who spurred the people of Paris on. In a speech before the Legislative Assembly on September 2, Minister of Justice Georges Danton urged Parisians to action: “The tocsin we are about to sound is not a warning signal; it sounds the charge on the enemies of our country. To conquer them we need boldness, more boldness, always boldness, and France is saved!” [6] Many people were convinced even at the time that his intemperate speech would help to incite the attacks that would follow; it was on the afternoon of September 2 that the massacres began.

The first people murdered were counterrevolutionary priests in the process of being transported to the Abbaye prison, the place Marat had singled out. Priests, associated with counterrevolutionary forces because of the Catholic Church’s implacable opposition to the Revolution, would be among the major victims of the attack. The killings quickly spread to other prisons, where self-styled “patriots” sought to eliminate those involved in treasonous plots against the nation. By the time the slaughter ended on September 6, somewhere between 1100-1400 people had died. Only about 1/3 of those killed were political prisoners or conspirators against the government; the majority were common criminals, many locked up for minor offenses.

The murders were widely denounced both in France and abroad. A British diplomat described “the fury of the enraged populace” who slaughtered prisoners “with circumstances of barbarity too shocking to describe.” However, the “Septembriseurs” who carried out the massacres, many of them National Guard troops and Fédérés from the provinces preparing to head off to the war front, considered themselves true patriots. They were firmly convinced that they were performing work essential to the safety of the country. A number of journalists and politicians praised their actions in the immediate aftermath of the murders. But complicity in the September massacres eventually became a source of shame. Danton and a number of other French politicians would be accused of either encouraging the massacres or not doing enough to stop them. Even today, historians find it difficult to determine exactly what role certain politicians played in the massacres, in some cases because they took steps to hide their role from history as it became more problematic to be associated with them.

3. Rarely is one individual solely responsible for instigating an attack on democratic institutions and a regime of violence

The nearly two-year period that followed the September Massacres was tumultuous. King Louis XVI went on trial that fall and was executed on January 21, 1793. The French found themselves at war with most of Europe as England, Spain, and Portugal joined the coalition; in addition, civil war broke out in the Vendée and a number a French cities, leaving the government battling on all fronts. The effort to fight the war abroad and to quell counterrevolution within the country was the excuse for the Reign of Terror.

Some have seen the September Massacres as the first act in the Reign of Terror. [7]The Terror was an effort to rid France of counterrevolutionary elements and to prosecute the war abroad. It resulted in the execution by guillotine of about 17,000 people throughout France, but many more in the civil war and extralegal killings. The Terror had the support of most Jacobins, the most radical of the revolutionaries, as well as many people who wanted to see the gains of the Revolution preserved. By the spring and summer of 1794, however, it had come to be seen by opponents, and even some earlier supporters, as too brutal and too indiscriminate. This was especially true with the passage of the Law of 22 Prairial, which limited the ability of the accused to defend themselves, and made it easier to convict and execute defendants. The result was that executions in Paris increased dramatically in June and July of 1794.

The politician most closely linked with the Terror is Maximilien Robespierre, a Jacobin and member of the Committee of Public Safety. Yet historians today are less convinced that Robespierre is solely or even primarily to blame for it. Marisa Linton makes a convincing case that while Robespierre bears heavy responsibility for his role in the Terror, especially because of his role in passing the Law of 22 Prairial, “By loading the blame on to Robespierre, making him ‘take the rap for the terror’, we avoid looking at more profound reasons, more troubling reasons, why terror developed.” So why did Robespierre become the face of the Terror?

By the summer of 1794, the degree of political infighting within the National Convention had increased dramatically. A number of the original Revolutionary leaders, such as Danton, had gone to the guillotine by this point, sometimes as a result of Robespierre’s denunciations of those he considered insufficiently committed to the Revolutionary cause. Some of Robespierre’s fellow revolutionaries began to worry that he was planning to go after them next. This fear was heightened on July 26, when Robespierre gave a speech before the National Convention in which he suggested (ominously for those listening) that there were traitors within the National Convention itself whom he was ready to expose. This brought together a group of legislators, fearful for their own lives, who put aside their own differences to take Robespierre down, including among others Jean-Marie Collot d’Herbois, Jacques-Nicolas Billaud-Varennes, and Jean-Lambert Tallien. These men, called the “Thermidorians” (drawn from the name of the month Thermidor in the Revolutionary calendar), launched their offensive in a series of dramatic speeches before the National Convention on July 27 (9 Thermidor). Their accusations led to the arrest and swift trial of Robespierre, his two closest associates, and his brother. The four men went to the guillotine the next day, done in by the laws that they themselves had helped pass.

In the months that followed these executions, the French people had to come to grips with what had been for so many people a period of trauma. The people most at risk in the fall of 1794 and into 1795 were the politicians who had participated in the Terror themselves but survived the purge of Robespierre and his closest collaborators. It was, in fact, those legislators most implicated in the machinery of the Terror who led the attack on Robespierre. Now, with Robespierre out of the way, the men who brought him down needed to find a way to convince the French public that it was Robespierre and his small group of followers who were responsible for the excesses of the Terror, not them, and, at the same time, to re-establish a stable government—no easy task. A month after the death of Robespierre, Tallien, a prominent Thermidorian, gave a famous speech in which he described “a system of Terror” whose machinery had pulled in members of the National Convention even as it oppressed French citizens. [8] He tried to make the case that Robespierre was the man responsible for the Terror, and that his execution would allow the French to put this awful episode of violence behind them.

But that was easier said than done. A pamphlet called La queue de Robespierre (Robespierre’s Tail) suggested that while Robespierre’s head had been cut off, his radical Jacobin followers were still active. French legislators continued to investigate and condemn those responsible for the worst excesses of the Terror. Some of them were exiled, others executed. Those held accountable included some of the men responsible for taking down Robespierre, such as Collot-d’Herbois and Billaud-Varennes. But many more evaded responsibility and helped shape the next government.

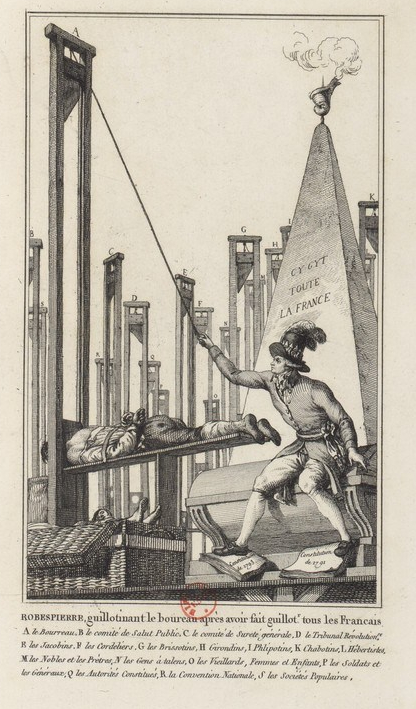

There was one way, however, in which the Thermidorians were successful: they created a narrative that fixed the responsibility for the Terror on Robespierre. In the popular imagination even today, Robespierre is to blame for the Terror. This narrative made its way into newspapers and popular iconography almost as soon as he was executed. A famous cartoon of Robespierre executing the executioner after having executed everyone else in Paris was widely distributed.

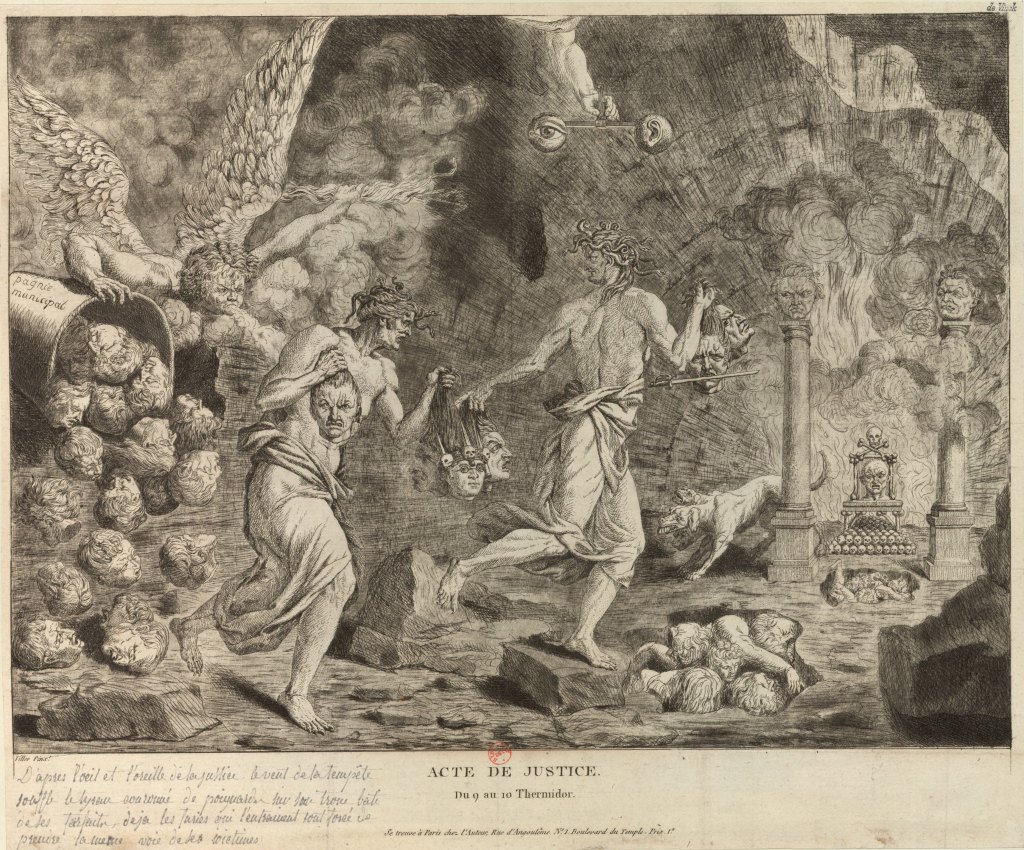

More gruesome images, drawing on classical imagery, portray Robespierre’s death as divine retribution, with his severed head joining those whose death he caused.

4. When politicians question and undermine the results of elections—or representative institutions more generally—citizens become more cynical and less committed to democracy, which is enormously damaging in the long run.

But while the Thermidorians were successful in making Robespierre the face of the Terror, the regime of moderate republicans that followed, the Directory, faced immense challenges that Robespierre’s death couldn’t solve. The nation was still at war and facing immense economic hardships. And even though the politicians of the Directory were not monarchists, they lacked a genuine commitment to democratic institutions, even with Robespierre gone. They overturned what they considered problematic election results in both 1797 and 1798, known as the Coup of 18 Fructidor and the Coup of 22 Floréal, respectively. These actions lessened the French public’s commitment to democratic institutions, convincing them that all politicians were corrupt and self-serving. The cynicism and distrust of the Directorial regime opened the path for the young and charismatic general Napoleon Bonaparte to come to power in a coup on the 18th Brumaire (November 9, 1799).

Lessons for today?

History does not repeat itself. I would argue that contingency plays the predominant role in the unfolding of history. The circumstances that the United States is facing today are profoundly different from those confronting revolutionaries in France in the 1790s. And yet, we also live in a world where lies and conspiracy theories are amplified by social media and the internet. After two months of accusations of a rigged and stolen election and exhortations to come to Washington to “Stop the Steal,” all it took was an intemperate speech by former President Trump on January 6 to spur his inflamed followers, convinced that they were defending the nation, to storm the Capitol—with predictable results.

Even more sobering, we know that our country’s problems will not end even now after Donald Trump has left office. We have learned that there are a lot of people in this country—including some on Capitol Hill—who are not fully committed to our democratic institutions and who are willing to play with the forces of extremism. While there is cause for hope, we must not forget that this extremism continues to exist. Our politicians should keep in mind that while undercutting faith in democratic institutions may sometimes lead to short-term political gain, the long-term effects are profoundly damaging.

A dangerous chapter in U.S. political history has come to a close, and we do not know how things will look four years from now. But history suggests that we need to be vigilant in guarding our democratic institutions, and to grapple seriously with the economic, social, cultural, and political divisions that continue to define us.

Christine Adams is professor of history at St. Mary’s College of Maryland. An Andrew W. Mellon fellow at the Newberry Library in Chicago and fellow at the American Council of Learned Societies, her current book project examines the Merveilleuses and their impact on the French social and historical imaginary, 1794–1799 and beyond.

Title image: Siege of the Tuileries, 1792.

Further reading:

Andress, David. The Terror: The Merciless War in Revolutionary France. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006.

Brown, Howard G. and Judith A. Miller, eds. Taking Liberties: Problems of a New Order from the French Revolution to Napoleon. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002.

Brown, Howard G. Ending the French Revolution: Violence, Justice, and Repression from the Terror to Napoleon. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006.

Linton, Marisa. Virtue, Friendship, and Authenticity in the French Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Mason, Laura. “The Culture of Reaction: Demobilizing the People after Thermidor.” French Historical Studies 39:3 (August 2016): 445-70.

McPhee, Peter. Liberty of Death: The French Revolution. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016.

Miller, Mary Ashburn. A Natural History of Revolution: Violence and Nature in the French Revolutionary Imagination, 1789-1794. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011.

Tackett, Timothy. The Coming of the Terror in the French Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Endnotes:

[1] Margaret MacMillan, Dangerous Games: The Uses and Abuses of History (New York: The Modern Library 2009), 153.

[2] Jack R. Censer, Prelude to Power: The Parisian Radical Press, 1789-1791 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976), 48-55.

[3] Elizabeth Cross, “The Myth of the Foreign Enemy? The Brunswick Manifesto and the Radicalization of the French Revolution.” French History 25, no. 2 (2011): 188-213.

[4] David A. Bell, The First Total War: Napoleon’s Europe and the Birth of Warfare as We Know It (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2007), 138-39.

[5] Quoted in Warren Roberts, Jacques-Louis David and Jean-Louis Prieur, Revolutionary Artists: The Public, the Populace, and Image of the French Revolution (Albany: State University of New York, 2000), 181.

[6] Discours de Danton, ed. André Fribourg (Paris: E. Cornély, 1910), 173. Translation mine.

[7] See Mona Ozouf, “War and Terror in French Revolutionary Discours, 1792-1794), Journal of Modern History 56: 4 (Dec. 1894), 579-97, esp. 582 and 585.

[8] Bronislaw Baczko, Ending the Terror: The French Revolution after Robespierre, trans. Michel Petheram. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 49.

[9] Howard G. Brown, “Robespierre’s Tail” The Possibilities of Justice after the Terror,” Canadian Journal of History 45 (2010): 303-35.