By Matthew Kerry

In October 1934 revolutionary militias led by socialist leaders stormed cities across Spain. The former Minister of the Interior, Rafael Salazar Alonso, was arrested on crossing the border from Portugal. Socialist revolution had triumphed and overcome the desperate resistance of the army.[1] Except they didn’t, he wasn’t, and it hadn’t. None of these claims were true.

But this did not mean that October in Spain was peaceful. For two weeks, the northern region of Asturias was the scene of a revolutionary insurrection. In areas under revolutionary control, this “fake news” was plastered on walls and read aloud by militia patrols. Despite short-lived uprisings, strikes, and shootouts across the country—and the short-lived declaration of a Catalan state within a federal republic in Barcelona—only in Asturias did events take the form of a large-scale revolt. As militias fought government forces in the streets of the city of Oviedo, revolutionary committees in the rear-guard formed of socialists, anarchists, and communists sought to organize a combination of revolution and war effort by banning money, seizing and distributing food supplies, reorganizing medical care, and organizing a rudimentary armaments industry. The arrival of reinforcements from Spanish Morocco and garrisons across Spain to support the beleaguered armed and security forces turned the tide and overcame revolutionary resistance. Approximately 1,500 died.

What are we to make of this episode? Historians of interwar Europe often neglect or reduce the Asturian October to the category of a “strike,” perhaps due to the difficulties in recognizing a revolution in a decade defined by fascist advance and left-wing retreat.[2] In the context of 1930s Spain, much of the debate has centred on whether the uprising was “offensive” or “defensive” towards the Second Republic—a reformist, secularizing regime founded in 1931 on ideals of equality, justice and democracy.[3] The Asturian October accordingly either emerged from fears of a possible authoritarian or fascist shift in the Spanish government or proved socialists’ lack of democratic credentials, for it was the socialist leadership in Madrid who planned the hazily defined “revolutionary movement.” How to relate the Asturian October to its historical context—and the Civil War in particular—is a thorny matter. The Francoist legal instruments introduced to punish the defeated in the Civil War were backdated to the Asturian October, thereby projecting 1934 as the starting point for the War.

But there are other underlying reasons as to why the revolutionary nature of this insurrection is downplayed. Scholars tend to approach October as an event and to frame it within national politics. But if we think about it as an unfolding process that was necessarily contested, we gain a better understanding of the Asturian October as a revolution that both was and wasn’t, at once unfinished, contradictory, and multifaceted.[4] Paying closer attention to fake news can help us with this task.

The proclamations produced by the revolutionary committees printed not only fake news, but also a variety of instructions and warnings, from details of the distribution of foodstuffs to threats of punishment for engaging in looting. On the one hand, it is understandable that scholars have paid these documents scant attention: their authorship is often unknown and the grandiose rhetoric did not match reality. The “Red Army” that the revolutionaries claimed to mobilize was little more than wishful thinking.[5] Yet the documents do provide rich material for the historian, and the memoir of Ceferino Álvarez, a communist miner, provides us with clues as to how we should interpret them. As he later wrote, “we were always objective and limited ourselves to what was really happening, to what was true and to what we were hoping for.”[vi] We should take the rhetoric of the proclamations seriously as an attempt by the authors to define themselves as revolutionaries, to describe the situation in which they found themselves, and simultaneously to conjure a new reality into being.

Proclaiming the death of the old society and the birth of a new world reveals the early days of the insurrection to have been a vertiginous moment of revolutionary possibility.[7] There was a mobilizing intent behind the false claims that militias were victorious across Spain, but such news, combined with the invocation of the storming of the Bastille in France in 1789 and the example set by the Bolsheviks in Russia, embroidered local events into a much broader, grander tapestry of revolutionary struggle, both geographically and temporally.[8] The extravagant—and soon hubristic—rhetoric reveals the coordinates according to which the would-be revolutionaries attempted to navigate the situation, even if the daily reality of the insurrection meant that revolutionary practice was messier and more contradictory.

As defeat loomed, the revolutionary committees began the process of historicizing the events on their own terms, folding the Asturian October into a history of defeat on the road to a final victory. Having “proved their revolutionary mettle” in combat, the proletariat had to lay down their arms and return to work, described as “a parenthesis, a revitalizing rest” in the course of revolutionary struggle.[9] In the months that followed, the revolutionary character of the insurrection was not disputed. It became a badge of identity for communists and socialists, particularly at the local level in Asturias, even if the socialist leadership distanced themselves from the uprising. For the political right, locally and nationally, the Asturian October materialized the threat of Bolshevik-style destruction on Spanish soil.[10]

If judged according to its effects in reconfiguring the social, economic, and political order, the Asturian was evidently a failure. Yet defining the Asturian October in terms of its outcome erases the dreams and objectives of the enthusiastic proponents of revolutionary change in 1934 and consigns them to the condescension of posterity. The proclamations, which are the only surviving sources produced during the insurrection itself, provide insight into mentalities in the heat of the moment. They also underline the importance of reframing the insurrection as a contested and evolving process, and a multifaceted event, in which plans hatched in Madrid did not correspond with the reality in the coal valleys of Asturias. The fake news produced during the insurrection remain as testaments of a revolution proclaimed, but a revolution that never really was.

Matthew Kerry is Lecturer in European History at the University of Stirling. He received his PhD from the University of Sheffield in 2015 and has been a research fellow at York University, the Institute for Social Movements (Bochum), and the Centre for Ibero-American History (Leeds). He is the author of Unite, Proletarian Brothers! Radicalism and Revolution in the Spanish Second Republic, 1931-1936, which is available open access. His work on 1930s Spain has also appeared in the English Historical Review, European History Quarterly, and Cultural & Social History.

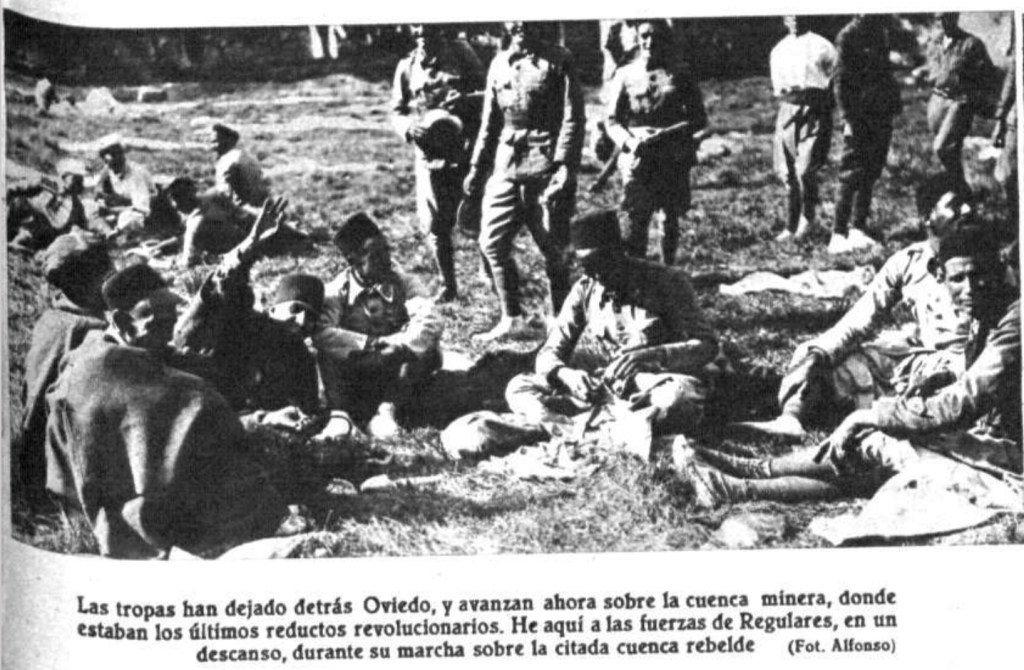

Title image: Would-be revolutionaries arrested in Brañosera, Palencia, 1934. This is the most famous photograph of October 1934.

Further Readings:

Bunk, Brian D., Ghosts of Passion: Martyrdom, Gender, and the Origins of the Spanish Civil War. Durham, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Kerry, Matthew. Unite, Proletarian Brothers! Radicalism and Revolution in the Spanish Second Republic, 1931-1936. London: University of London Press, 2020.

Shubert, Adrian. The Road to Revolution in Spain: The Coal Miners of Asturias, 1860–1934. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 1987.

Taibo II, Paco Ignacio. Asturias, Octubre 1934. Barcelona: Planeta, 2013.

Endnotes:

[1] “Noticias oficiales de la revolución,” reproduced in Aurelio de Llano Roza de Ampudia, Pequeños anales de quince días. Revolución en Asturias octubre de 1934 (Oviedo: Altamirano, 1935), 150-1.

[2] E.g. the recent Penguin History of Europe: Ian Kershaw, To Hell and Back: Europe 1914-1949 (London: Penguin, 2016), 304.

[3] Ruiz labels it a “defensive insurrection” in Insurrección defensiva y revolución obrera (Barcelona: Labor, 1988). On October 1934 as defensive and offensive in the context of the Republic respectively, e.g. Paul Preston, The Coming of the Spanish Civil War: Reform, Reaction and Revolution in the Second Republic (London: Macmillan, 1978) and Stanley Payne, The Collapse of the Spanish Second Republic, 1933-6 (New Haven: Yale UP, 2006).

[4] For further ways of approaching the Asturian October as contested and contradictory see Chapter 5, “Revolution,” in Matthew Kerry, Unite, Proletarian Brothers! Radicalism and Revolution in the Spanish Second Republic, 1931-1936 (London: University of London Press, 2020).

[5] E.g. “Noticias de Madrid,” in Narciso Molins i Fábrega, UHP: La insurrección proletaria de Asturias (Madrid: Júcar, 1977), 136.

[6] Conchita Fontalbat and Ceferino Álvarez, Ceferino Álvarez Rey: historia de un minero de Asturias (Oviedo: KRK, 2010), 85.

[7] “A los trabajadores y campesinos del concejo de Grado,” in de Llano Roza de Ampudia, Pequeños anales, 147-9.

[8] “El comité provincial revolucionario de Asturias,” in Molins i Fábrega, 130-1.

[9] “El comité provincial revolucionario de Asturias,” in de Llano Roza de Ampudia, Pequeños anales, 202.

[10] On the political uses and “invention” of October 1934, see Brian D. Bunk, Ghosts of Passion: Martyrdom, Gender, and the origins of the Spanish Civil War (Durham, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2007) and Rafael Cruz, En el nombre del pueblo: república, rebelión y guerra en la España de 1936 (Madrid: Siglo XXI, 2006), 70ff.