By Luke Reynolds

The announcement of Joaquin Phoenix as Napoleon Bonaparte in Napoleon, Sir Ridley Scott’s upcoming epic historical drama, sparked a round of the online discourse that major film casting news inevitably does these days. Whether Phoenix’s performance satisfies critics, professional or anonymous, or even wins him another Oscar, it will be a tall order for him to rival the portrayal of Bonaparte that shaped an entire generation’s image of the first Emperor of the French.

Depending on your preference, age, nationality, and cultural upbringing, you might be nodding, thinking of Albert Dieudonné, Marlon Brando, Vladislav Strzhelchik, Rod Steiger, or, perhaps, Terry Camilleri, but I am not referring to any of those actors. I am referring to a man and a performance last witnessed over 170 years ago. Please allow me to introduce Edward Alexander Gomersal, the man who was, for thirty years in the mid-nineteenth century, the celebrated and unparalleled representation of Bonaparte for theatre-going Britons.

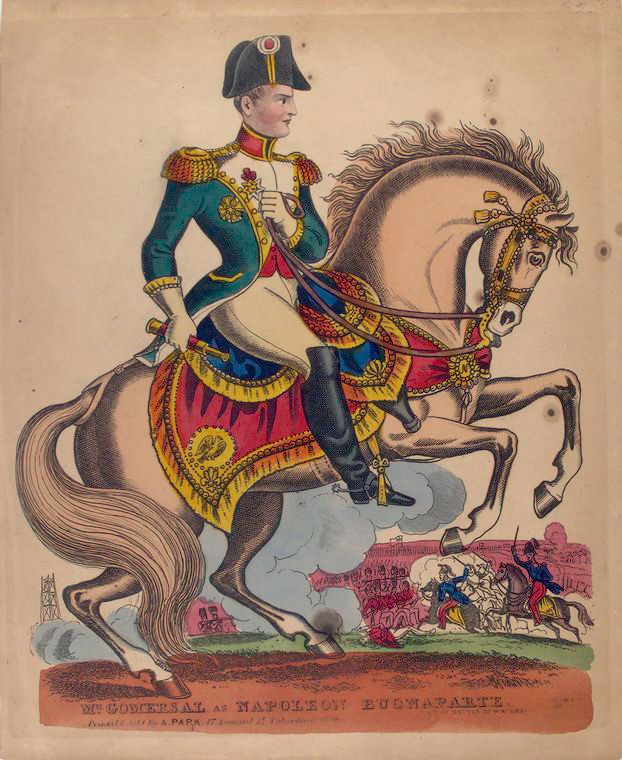

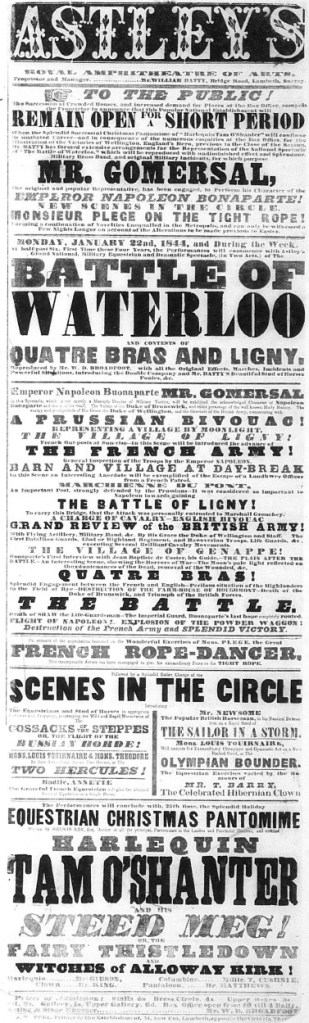

I first encountered Gomersal while researching Who Owned Waterloo? Battle, Memory, & Myth in British History, 1815-1852. I came across an illustration of him as Bonaparte in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Theatre and Performance Collections which brought to my attention the hippodrama that made him famous, J. H. Amherst’s The Battle of Waterloo. Gomersal, the son of a British army officer, had been destined for a career in banking before abandoning it for the stage. He was in his mid-thirties when The Battle of Waterloo debuted at Astley’s Royal Amphitheatre in London on April 19, 1824 and became an instant hit.[i] In fact, to call The Battle of Waterloo a hit is an understatement. Its opening run lasted 144 consecutive performances – the entirety of the 1824 season, which was by no means a given in London’s cutthroat theatrical scene – and drew at least a quarter of a million people to Astley’s. The next 45 years saw regular successful revivals, with its final recorded performance in June of 1869.[ii] In 1864, The Timesdeclared it one of the two most successful pieces “ever brought out at Astley’s.”[iii]

For more than half of The Battle of Waterloo’s cultural life, one of the features that punters and press alike looked for in any revival was whether Gomersal would be returning as Bonaparte, the role he invented and made him famous. This fascination with a single performer was in itself remarkable. The Battle of Waterloo was a hippodrama, selling itself on a heady mix of equestrian action and melodramatic relationships; it was every kind of spectacle theatre audiences loved. But, unlike in Scott’s Napoleon, here the Emperor led no cavalry charges. Although a central character, he was not part of the spectacle – his equestrian exploits began and ended with entering and exiting on his white charger. Rather than trade sword thrusts, he bandied words, inspired his troops, and (crucially for verisimilitude) took snuff.[iv]

Even as romantic and patriotic love raged around him, comic songs were sung, and massive battle scenes saw the deaths of the Duke of Brunswick and Corporal John Shaw of the 2nd Life Guards, it was “the character of Napoleon as performed by Mr. Gomersal [who was] the nightly theme of admiration.”[v] Part of this was due to the fact that he was, by all accounts, a facsimile of Bonaparte (at least to people yards away who had only ever seen the actual emperor in paintings, statues, caricatures, or chamber pots). The composer Walter Macfarren, who saw the production multiple times when he was a student at the Royal Academy of Music, recorded that Gomersall “resembled [Napoleon] to a nicety,” while The Morning Post admitted the similarity was “striking.”[vi] The likeness even made its way into the cannon of English literature: William Makepeace Thackeray’s Colonel Newcome “was amazed – amazed, by Jove, sir – at the prodigious likeness of the principal actor to the Emperor Napoleon.”[vii] Gomersal’s performance lived up to his appearance. In one review of the hippodrama’s 1844 revival, The Era dedicated more than half their reviewing to praising “Mr. Gomersal’s personation of Napoleon,” declaring

It is enough to say he played with all the freshness and vigor which rendered his first delimitation of the character of this extraordinary man an immediate and decided favorite with the public. The vanity which conceals itself under apparent rudeness and asperity, that trembling consciousness of a desire to have the world think him the greatest man in it, which peeps forth in Gomersal’s Napoleon, even while assuming a lofty contempt of the world’s opinion, was highly characteristic of a man whose position enabled him to live for posterity, and who was animated by a self-love ever cherished by the human heart. Gomersal’s acting judiciously betrays the restlessness of one who would be every thing, and such a man was Napoleon, who, with all his greatness, could be so little on occasion.[viii]

Perhaps Gomersal’s greatest notice, however, came from a mentally unstable audience member in Dublin who was so taken in that the man leapt onto the stage “for the purpose of having an interview with Napoleon.”[ix]

Gomersal’s renown as Bonaparte translated into wider theatrical success, not always on horseback. Within two weeks of The Battle of Waterloo closing on October 2, 1824, he was playing the title role in Valmondi; or, The Unhallowed Sepulchre at the Adelphi Theatre and would go on to co-manage the Garrick Theatre for six years in the 1840s.[x] Despite this he was, for good or ill, now permanently typecast as the Emperor; he played Bonaparte in other productions, most notably the hippodramas Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia; Or, The Conflagration of Moscow and The Life and Death of Napoleon Buonaparte, both for Astley’s, as well as the traditional plays Paulina, or the Passage of the Beresina for the Adelphi and The Death of Napoleon for the Royal Victoria Theatre.

Much like for Bonaparte himself, for Gomersal The Battle of Waterloo was always lurking in the background.[xi]In 1831, in a review of The Days of Athens at the Drury Lane Theatre, The Standard lamented that they “would much rather see [Gomersal] play Napoleon at the scene of his proper glory, Astley’s Amphitheatre.”[xii] Given the continued popularity of The Battle of Waterloo, The Standard had plenty of opportunities to do so. For revivals as early as 1828 and as late as 1849, Gomersal received top billing as “the favourite representative of Napoleon Bonaparte.”[xiii]

Gomersal’s superiority in the role was not merely good advertising on the part of Astley’s copywriters. He set the standard for the British understanding of the Emperor. In the spring of 1831, three different actors portrayed Bonaparte on three different stages in London. In their review of the production appearing at the Surrey Theatre, The Examinerdeclared, “Mr. Osbaldiston falls as far short of Ward’s picture of Buonaparte, as Ward does of Gomersal.”[xiv] Twenty-two years later, in one of the first revivals of The Battle of Waterloo that he was not a part of, the Morning Post paid his successor, a Mr. Stephens, the compliment that his shoulders held up well under “the mantle of the great and imperial Gomersal.”[xv] He became a great favorite of Punch, who dubbed him “the Emperor Gomersal” and used him extensively to lampoon French politics.[xvi] During the period between the 1848 Revolution and the stabilization of the Second Empire, they suggested multiple times that he should journey to Paris and seize power by popular acclaim, insisting he “might be crowned Emperor at Notre Dame before Louis would have time to protest in the name of himself and family.”[xvii] Closer to home, The Leicestershire Mercury used him in 1853 to poke fun at the Ultra-Tory Colonel Sibthorp, reporting that at a local militia review, Sibthorp “has been playing the part of a Lincolnshire Napoleon with all the gusto of a Gomersal.”[xviii]

Gomersal died on October 19, 1862, leaving behind multiple sons who had followed their father into the theatrical business. Every obituary, even those only four lines long, mentioned his fame as Bonaparte, with The Era referring to him as “Napoleon Gomersal” and noting that they believed “he acted Napoleon in every Amphitheatre in Britain.”[xix] For two generations, Gomersal simply was Bonaparte. He played a part in turning the Emperor of the French from Britain’s ultimate bogeyman into “Napoleon the Great.”[xx] Given that, there is a case to be made that Gomersal took snuff on stage so Phoenix could play the on-screen hero that “came from nothing” and “conquered everything.”

Luke Reynolds is an Assistant Professor in Residence at the University of Connecticut’s Stamford Campus. He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, Secretary of the Napoleonic and Revolutionary War Graves Charity, and a member of the Lambs. His first book, Who Owned Waterloo? Battle, Memory, and Myth in British History, 1815-1852(Oxford University Press, 2022) won the 2023 Society for Military History Distinguished Book Award in the First Book Category and was a runner up for the Society of Army Historical Research’s 2023 Best First Book Prize. It will be published in paperback by Oxford University Press in November 2023.

Title image: “Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library. “Mr. Gomersal as Napoleon Buonaparte [Bonaparte] [in The Battle on Waterloo]” New York Public Library Digital Collections.”

Further Reading:

Assael, Brenda. The Circus and Victorian Society. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2005.

Hoock, Holger. Empires of the Imagination: Politics, War, and the Arts in the British World, 1750-1850. London: Profile Books, 2010.

Saxon, A. H. Enter Foot and Horse: A History of the Hippodrama in England and France. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1968.

Semmel, Stuart. Napoleon and the British. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

Valladares, Susan. Staging the Peninsular War: English Theatres 1807-1815. London: Routledge, 2016.

Endnotes:

[i] Births, Deaths, Marriages and Obituaries, The Era, October 26, 1862, p. 10.

[ii] Luke Reynolds, Who Owned Waterloo: Battle, Memory, & Myth in British History¸1815-1852 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), 151-159.

[iii] Astley’s Theatre, The Times, October 7, 1864, p. 7.

[iv] J. H. Amherst, The Battle of Waterloo, A Grand Military Melo-Drama in Three Acts (London: Duncombe, 1824). In a review of the 1838 revival, The Morning Post took Gomersal to task for “not, during the whole performance tak[ing] a single pinch of snuff.” The Theatres, Morning Post, April 17, 1838, p. 3.

[v] Royal Amphitheatre, The Drama; or, Theatrical Pocket Magazine, June, 1824, vol. VI, no. 4, 201.

[vi] Walter Macfarren, Memories: An Autobiography (London: The Walter Scott Publishing Co., Ltd., 1905), 25-26; Astley’s Amphitheatre, Morning Post, May 19, 1831, p. 3.

[vii] William Makepeace Thackeray, The Newcomes (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., 1910), I:170.

[viii] Music and the Drama, The Era, January 28, 1844, p. 6.

[ix] Dublin Theatre, Morning Chronicle, January 26, 1825, p. 2.

[x] The Minor Theatres, Morning Post, October 4, 1824, p. 3; Morning Post, October 19, 1824, p. 1; The Theatres, The Era, October 18, 1840, p. 2; Dancing and Music Licenses, The Era, October 23, 1842, p. 7; Public Amusements for the Week, Lloyds Illustrated Newspaper, November 8, 1846, p. 6.

[xi] Astley’s Amphitheatre, The Drama; or, Theatrical Pocket Magazine, May 1825, p. 426; Astley’s Amphitheatre, Morning Post, May 19, 1831, p. 3.

[xii] Drury-Lane Theatre, The Standard, November 15, 1831, p. 1.

[xiii] Examiner, September 7, 1828, p. 8; Astley’s Handbill for December 10, 1849, British Library, Playbills 172. The last mention I can find of him playing the Emperor was in 1855, when he assumed the role at a benefit for his son at Manchester’s Queen’s Theatre. Provincial Theatricals, The Era, July 8, 1855, p. 11.

[xiv] Theatrical Examiner, Examiner, May 29, 1831, p. 6.

[xv] Astley’s Amphitheatre, Morning Post, November 8, 1853, p. 5.

[xvi] A visit to Astley’s Punch, or the London Charivari Vol. 16 (London: Punch, 1849), 123.

[xvii] Punch’s Idées Napoléennes, Punch, or the London Charivari Vol. 17 (London: Punch, 1849), 224; The Future Rulers of France, Hampshire/Portsmouth Telegraph, October 30, 1852, p. 7. In fact, Gomersal had at least some recognition in France, as one fellow Napoleon impersonator was reported to credit himself as “The French Gomersal.” J. Keith Angus, A Scotch Play-House; Being the Historical Records of the Old Theatre Royal, Marischal Street, Aberdeen (Aberdeen: D. Wyllie & Son, 1878), 28.

[xviii] The Soldier Sibthorpe, Leicestershire Mercury, June 4, 1853, p. 4.

[xix] Births, Deaths, Marriages and Obituaries, The Era, October 26, 1862, p. 10; Births, Deaths, Marriages and Obituaries, Birmingham Gazette, October 25, 1862, p. 8; General News of the Week, Stamford Mercury, November 7, 1862, p. 3; Musical and Dramatic Chronology for 1862, The Era, January 4, 1863, p. 14.

[xx] Births, Deaths, Marriages and Obituaries, Birmingham Gazette, October 25, 1862, p. 8. Stuart Semmel, Napoleon and the British (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004); Nicole Cochrane and Matilda Greig, eds., Napoleonic Objects and their Afterlives: Art, Culture and Heritage, 1821-present (London, Bloomsbury, 2024).