By Suzanne Levin

In recent years, debates about the “Terror” in the French Revolution have been enriched with several new perspectives. Despite this, the many works attempting to seek the “origins” of the “Terror” often take this inherited category for granted. Some scholars have nonetheless begun to interrogate or even deconstruct the “Terror”: Can we speak of the “Terror” as a unitary system, while recognizing its improvised and variable character?[1] Can we even evoke it as a straightforward reality, when it originated as a post-hoc ideological construct,[2] one meant moreover to discredit not only the violence and repression of 1793-1794, but also its democratic and social experimentation?[3] Might the continued usage of the chrononym “Terror” obscure more than it explains, reifying, among other myths, that of the French Revolution’s exceptionality?[4]

One approach that has proven fruitful in this reinterrogation of the “Terror,” has been to study how historical actors used the term “terror.”[5] The present article, drawn from my doctoral research on representative on mission and Committee of Public Safety member Pierre-Louis Prieur of the Marne, focuses on one overlooked aspect of these uses. The French National Convention never declared “terror” the “order of the day,” as Jean-Clément Martin has pointed out.[6] Yet, the phrase did gain traction with popular militants and was used by several representatives on mission sent from the Convention to the departments. Much attention has been paid to the “terror” portion of the phrase, but very little to the “order of the day.” What did it mean for terror to be order of the day? The example of Prieur of the Marne can help answer this question.

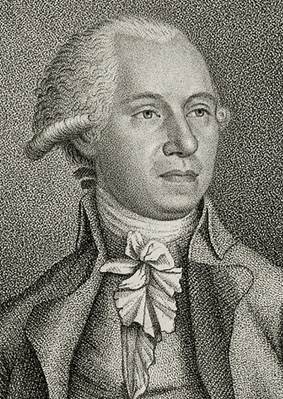

Jean-Baptiste Vérité, Portrait de Pierre-Louis Prieur, dit Prieur de la Marne, 1790

Like several other representatives, Prieur ordered that “terror” be placed “on the order of the day” in Vannes on the 10th day of the 2nd month of Year II (31 October 1793), toward the start of his eleven-month-long mission in the West of France.[7] This order is generally understood as Prieur’s inaugurating the regime of the “Terror” in the region.[8] Prieur waited ten days after his arrival to make this order, which would be strange, if he had intended to officially declare that the “Terror” had come to Vannes. But beyond this, we should also scrutinize the action of making something the “order of the day.” This is a term taken from parliamentary politics: when a subject is placed on the order of the day of an assembly, it is dealt with and then the assembly moved on. Its effects may be long-lasting, but the order of the day itself is not. By using this phrase in the context of an arrêté (decree), Prieur was likely trying to accomplish something precise.

In the preamble to his arrêté, Prieur explained that since “the city of Vannes has, up until today, fallen prey to fanaticism, aristocracy, royalism, and federalism…there is reason to presume that a large number of suspects, [refractory] priests, fanatical nuns, and émigrés have taken refuge within the city’s walls.” Therefore, according to Prieur, it was not possible to “complete the regeneration” of Vannes without taking measures against them.

The articles that follow clarify that these groups will be targeted through a series of clearly delineated measures, notably arrests and the confiscation of weapons or hoarded resources. Regarding the “order of the day,” the most interesting is article 7: “The execution of the present arrêté will take place starting at 10 in the morning, until the moment when the surveillance committee declares that its operations are finished.” Like all orders of the day, this one is limited. In this case, “operations” took only one day.

Prieur’s letter to his colleague Tréhouart seems to confirm that this limited timeframe was intentional:

Yesterday, by formal arrêté, I put terror against the enemies of the people as the order of the day. The city was surrounded, canons pointed, drums beaten, all the troops in arms. Domiciliary visits were made to every house and nearly two hundred suspects are currently under arrest. I believed that this measure was indispensable in a country needing regeneration, and tomorrow we celebrate the festival of sans-culottes.[9]

“Terror” had been placed as the order of the day; the “suspects” had been arrested. Now, Prieur’s letter confirmed, they could move on to celebrating a festival. Moreover, Prieur advised Tréhouart, then at nearby Belle-Île-sur-Mer that “it would be a very good measure for your island, this terror on the order of the day. Then (alors) you would transport any suspects to the mainland.” This suggests that one could take the measures associated with “terror as the order of the day” and “then” move on to something else.

Etienne Béricourt, Scène d’arrestation, époque révolutionnaire, 1784-1794

This is not to say that metaphorical uses did not exist. Prieur himself used the expression this way at least once, also in Brumaire Year II (October-November 1793). However, significantly, Prieur scarcely used the term “terror” at all after this point, although he remained active in Brittany throughout the Year II. Surely if he had viewed “terror” as the through-line of all his activity, he would have continued to hammer the point home.

Like many other revolutionaries, Prieur certainly intended to terrorize the declared enemies of the Republic. Like them, he was also aware that “terror” was a double-edged sword and tried to minimize it. Indeed, “terror on the order of the day,” with its one-and-done quality, may have been a strategy to do just that, all while repressing local Counter-Revolution. The use of “terror” could and did spiral out of control, as, in different ways, in the Vendée or what Marisa Linton calls the “politicians’ Terror.”[10] Arguably, Prieur was more successful than most in containing it in the Morbihan, where despite repeated uprisings and Chouan assassinations, he estimated the total number of prisoners at 1500 to 2000 out of a population of around 400,000, and there were no more than a handful of executions.[11] We should not underestimate the dampening effect that repression and a climate of suspicion inevitably had on dissent, even among the most ardent republicans. But should we not ask the question of whether to term every policy adopted in 1793-1794 as one of “terror/Terror”? The question of repression’s effects on other policies and their intentionality is an interesting one, but one that we cannot answer if those effects are assumed.

This example teaches us to be cautious in our use of inherited categories. Prieur and his contemporaries were not and could not be referring to the “Terror” as it is deployed in the historiography. Thus, Prieur’s arrêté did not establish the “Terror” in the Morbihan, but rather a series of specific repressive measures representing only one facet of his action as a representative on mission. While it makes sense to examine its effects, both intentional and unintentional, on other types of policies, we cannot simply assume “terror” as the essence of the revolutionary government, from which all other policies are tributary. Such a reading has its roots in the Thermidorian invention of the “Terror.” Prieur’s example joins with those cited by other scholars to urge further reexamination of this inheritance.

As for this example’s applicability to the present moment, it’s important to avoid the temptation of facile comparisons to current authoritarian regimes, allowed by the catch-all term of “populism.” Prieur and his colleagues were not fascists, and though they could take political rivals and even friends for enemies, the Counter-Revolution was neither a figment of their imagination nor an arbitrary scapegoat. On the contrary, they were grappling with a problem we still face today: how to defend democracy and human rights when their avowed enemies present a credible threat? Even as we may condemn many of the measures taken by revolutionaries like Prieur under the term “terror,” let us have the honesty to recognize that this is not a problem with an easy and obvious solution.

Suzanne Levin is a post-doctoral research fellow in the Turin Humanities Programme at the Fondazione 1563 in Turin, Italy. Her doctoral thesis was published in 2022 under the title La République de Prieur de la Marne. Défendre les droits de l’homme en état de guerre, 1792-an II.

Title Image: Execution of Robespierre and Saint-Just. Unknown Artist. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Further Reading:

Michel Biard and Hervé Leuwers, eds., Visages de la Terreur (Paris : Armand Colin, 2014).

Michel Biard and Marisa Linton, Terror: The French Revolution and its Demons (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2022).

Annie Jourdan, La Révolution française. Une histoire à repenser (Paris: Flammarion, 2021).

Suzanne Levin, La République de Prieur de la Marne (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2022).

Jean-Clément Martin, Les échos de la Terreur (Paris : Belin, 2018).

Endnotes:

[1] Michel Biard, ed., Les politiques de la Terreur (Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2008).

[2] Jean-Clément Martin, Les échos de la Terreur (Belin, 2018).

[3] Yannick Bosc, La terreur des droits de l’homme (Kimé, 2016).

[4] Annie Jourdan, Nouvelle histoire de la Révolution (Flammarion, 2018).

[5] Annie Jourdan, “Les discours de la terreur à l’époque révolutionnaire,” French Historical Studies 36, no. 1 (2013): 51-81; Cesare Vetter, “‘Système de terreur’ et ‘système de la terreur’ dans le lexique de la Révolution française,” Révolution-Française.net (Oct. 2014).

[6] Jean-Clément Martin, Violence et Révolution (Seuil, 2006), p. 186 & sq.

[7] French National Archives (AN), AF II 126, pl. 972, p. 14; AN AF II 125, pl. 959, p. 29; Departmental Archives of the Morbihan (AD Morbihan) L 1910.

[8] See for example, Bernard Frélaut, Les Bleus de Vannes (Société Polymathique du Morbihan, 1991).

[9] AN AF II 276, pl. 2316, p. 103.

[10] Marisa Linton, Choosing Terror (Oxford University Press, 2013).

[11] Prieur’s estimate, reprised by Greer, is currently the best we have, as Jean-Clément Martin laments in “Dénombrer les victimes de la Terreur” in Michel Biard and Hervé Leuwers, eds., Visages de la Terreur (Armand Colin, 2014).